I get asked a lot about health insurance claims. Having had many different diagnoses, surgeries, and procedures I have became all too familiar with interacting with insurance companies. In the last few years my diagnosis of breast cancer and the almost simultaneous diagnosis of our son Tristan with congenital spine and hand abnormalities has meant a level of paperwork, claims, and appeals I could never have imagined.

Navigating the maze of medical care and health insurance has become second nature to me. I think I’ve resisted writing this piece because initially I thought there wasn’t much to say. Having worked on this piece for weeks now, I realize the opposite is true: there is too much to say. Because each case is different it’s very hard to offer advice on what you, the reader, should do. But I’ve decided that’s the beauty of the blog format: I don’t have to cover all the bases. I don’t have to have all of the answers. I just need to do my best to help. And so today I’m starting to tackle this beast.

I’ve had many requests to write pieces about how to win against health insurance companies and many have suggested I go into this as a profession. I’m not sure about that one but I am definitely willing to share some of the insights I’ve learned throughout the past few years. I do think my upbringing in a medical household (my father was a cardiothoracic surgeon) helped familiarize me with medical terminology and how to correctly present a medical history. In addition to my tips you may be interested to read Wendell Potter’s recent advice in The New York Times: “A Health Insurance Insider Offers Words of Advice.”

Don’t take ‘no’ for an answer

The first piece of advice I have is simple: don’t take no for an answer. The fact your claim was denied is the starting point not the ending point. Insurance companies count on the fact that a large percentage of subscribers will receive a denial and either 1) forget about it, 2) intend to file an appeal but not follow through, or 3) incorrectly file the appeal paperwork (see Potter’s article, above). In any case, if they send you a claim denial and you don’t follow up for any reason, they win.

Always appeal

If you receive a rejection to a claim you feel you are entitled to always appeal. When I receive a claim denial I roll my eyes, roll up my sleeves, and say, “here we go again.” It’s what I expect, but it’s never the last word to me. Now, that is not to say that you always win– but it would take way more than one denial for me to accept that I’m not entitled to have a medical service covered. Persistence and determination are a large part of what it takes to win.

Physical (especially congenital) problems are easier to appeal than those related to developmental delays. I have little/no experience with appeals for diagnoses related solely to delays; while many of my general tips will still apply, more specific ideas will hopefully be available elsewhere online for those types of claims. I do know that when it comes to dealing with insurance companies those types of diagnoses are harder to quantify; this often leads to greater challenges with insurance appeals. In my experience, if the delays can be linked to anatomical problems, orthopedic issues, or diagnoses that can be validated with tests like MRIs or CTs, the case will be easier to justify.

Insurance companies must give you a reason whey they are denying a claim. Most often this reason is that 1) the treatment is experimental or investigational, 2) the treatment is not medically necessary, or 3) the treatment is not the standard of care.

In our case, initial denials have most often been because it wasn’t considered medically necessary.

Show the progression of the situation and how options have been exhausted

I always try to base appeals on the phrases “medical necessity” and “medically necessary.” When you document a surgery or service that you or your family member needs:

Be clear how it is necessary to daily functioning.

Describe what will happen if what you are asking for doesn’t happen.

Be sure to tell what you have tried already, and what has failed.

Show how your diagnosis and treatment history has brought you to this place–how there is no other reasonable option to what you are asking for (or how the alternative is not preferable).

Be complete but don’t ramble.

Be sure to include diagnosis codes and treatment codes (your medical professional will provide these).

Doctors’ offices don’t always have the final say

I should point out that a doctor’s office may tell you that you will have to pay out-of-pocket. They may tell you that they have tried to get your service covered, it was denied and therefore this is the last word. It’s not. For example, my neurologist’s office tried to get my Botox injections covered. Their office appealed the first rejection. They were again denied. They told me that there was “nothing else they could do”; I would have to pay.

Undeterred, I asked for copies of my medical records. I called my insurance company and asked what I needed to do. Despite what the doctor’s office told me, I learned that patients often have a separate appeals process available to them. While physicians’ offices can often get services covered and can be very helpful in knowing what’s been a successful method of appeal in the past, they are not the only way to get services approved. In a case like this there is actually a financial disincentive for them to have insurance cover it; therefore, they may not be as aggressive as you will. What does that mean? If I had paid out of pocket they would have received almost three times the amount of money that they receive when compensated by my insurance company directly.

When the office tried to get the injections covered, the insurance company denied the request on the basis that this was an experimental treatment– not FDA-approved for this use. I provided medical history sheets from my medical file. I documented every drug I had take until that point to try to prevent migraines and the dates I took them. I explained the medical condition/situation that resulted when I had migraines. I told them how the neurologist felt the Botox might help me. I included the original letter he had written to the insurance company. I explained that if they didn’t cover this treatment a more expensive, more medically damaging situation would result– this would mean more claims and more expense for the company. In the case of the migraines I documented how much my “rescue medications” were costing them per month and how a reduction in those would easily pay for the Botox I was asking for. I showed through my history with the numerous failed attempts with other drugs that the situation had not improved and in fact the side effects from those drugs had been debilitating. I also showed the literature about preliminary success in clinical trials with Botox and my neurologist’s observations about its efficacy in others and the potential efficacy in my case. I explained I had no other choice, and while it might be not-yet FDA approved, Botox was actually on the verge of receiving such approval (I was proved right when it did receive approval for this purpose less than one year after my request).

Include all relevant information and send appeal within the required time period

This letter of appeal doesn’t need to be 3 pages long. In fact, even in my most complicated appeals I didn’t write more than a page or two at most (plus the inclusion of the supporting documents). Be sure to appeal/respond within the time frame they dictate. In the letter be sure to include:

your contact information, subscriber number, and the doctor/hospital/treatment facility information

the case reference number that they provide

all relevant diagnosis and procedure codes

Ask doctors and staff for assistance, documents

Do not be afraid to ask your doctor and his/her staff for help: what tactics have they found useful? If there are multiple codes that apply which ones are the best to use? Do they have any sample letters for appealing? What has their experience been with your particular health insurance company?

Use the rejection letter as the foundation for your appeal

Take the rejection letter you received and read it carefully. Don’t just react with “it says no” and throw it away. It is vital; in it, the company must tell you why they are rejecting your claim (usually one of those three reasons I mentioned at the outset). This is the key to your appeal. You must address this issue. They’re telling you the basis, you need to fight based on that. Be thorough but don’t get off track.

Another good example of persistence in appeals came with a corrective band we used for Tristan’s quite-misshapen head (diagnoses of plagiocephaly and brachiocephaly). The facility we used for the DOC band told us that insurance claims were most often denied for this service. Indeed, the first claim was denied; they said the “helmet” to correct his misshapen head was for cosmetic reasons only. I appealed. I explained that because of his neck abnormalities the head deformity was an inevitable result of having his head fixed in one place. Because he was unable to move his head properly he had this inevitable result of a physical abnormality. I ended up having two helmets approved for coverage. Had I accepted the facility’s statement that “insurance companies usually don’t pay for this” or my first rejection letter from the company, we would have had to pay in full for both helmets. I should point out that I’ve seen success getting this particular service covered even when the plagiocephaly was not due to a unique condition like Tristan’s when the subscriber persisted with the appeal process.

You can appeal more than just a denied claim

– A facility that isn’t usually in-network may actually be considered in-network for some diagnoses. For example, Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital in New York City is a hospital that specializes in treatment of cancer. Though it isn’t normally included in coverage by some health plans, insurance companies will often allow oncology treatments there under the Centers of Excellence program. Through this policy, hospitals that specialize in certain conditions are treated as participating centers (in-network). So, if you wish to have medical care at a facility that specializes in a certain medical condition be sure to check whether they are included in this special program.

-Prescription drug plans can be adapted. This is a big one. What do I mean by this? Just because your prescription drug plan says it will only cover a certain number of pills doesnt mean that’s the last word. My prescription drug plan said only 9 pills of my expensive migraine medication would be covered each month. The problem? I frequently needed more than that number. I decided to investigate. I called my insurance company and the administrators of the prescription plan and asked how I could get that number increased because it was medically necessary for me to have more than that number. They said my doctor could call and make a request. He called and they agreed to cover 18 pills. I received a temporary increase to 18 pills a month for one year, renewable each year by going through the same process. That saves me up to $2880 a year.

-Additionally, numbers of physical therapy/occupational therapy visits can be appealed. Our plan covers 30 PT visits for Tristan per year. He needs significantly more than that number. When the 30 are up, I write and document the medical necessity for him to receive more based on his anatomical defects. I state the skills he is getting with the visits and how they are necessary for his functioning. The physical therapist sometimes needs to include a letter and our pediatrician needs to write a prescription for the services.

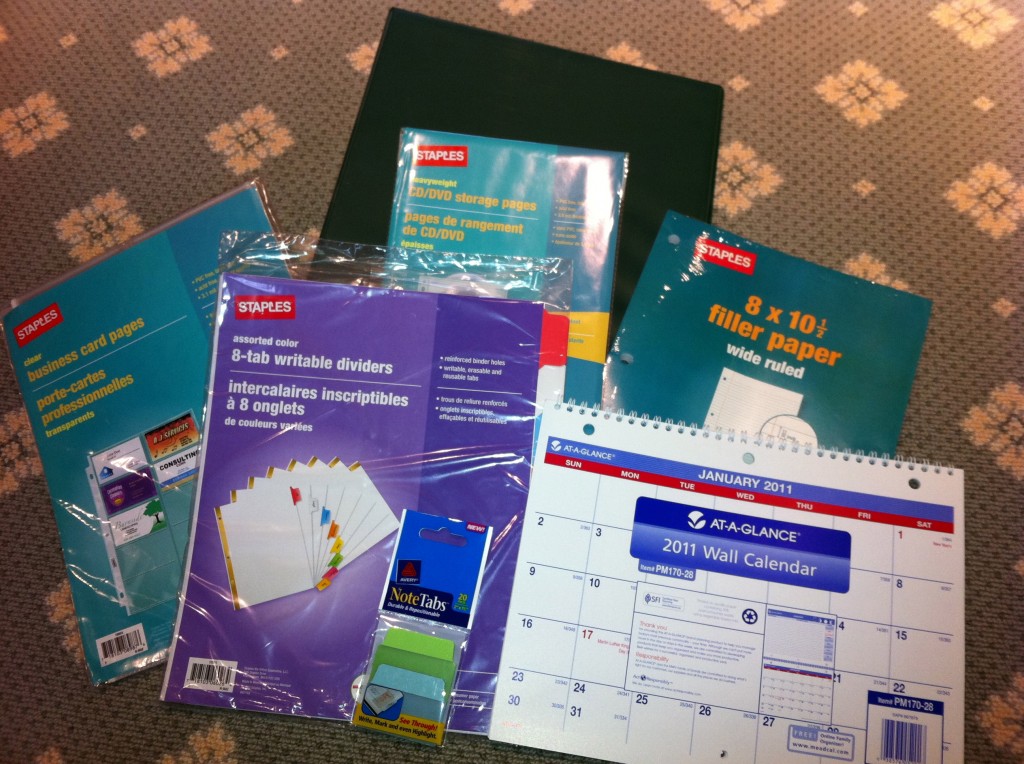

Be organized. Take notes. Document everything

No matter what drug, service, surgery, or treatment you are appealing, you must be organized, take notes, and document everything. The key to my system is my medical binder. Have one for each family member. To see how to organize this essential tool, read my blogpost here.

Keep copies of your lab results, operative notes, and copies of all communication to/from your insurance company.

Be sure to have a fully documented medical history.

Save letters that were successful; if you need to repeat an appeal annually (like my migraine drugs and Tristan’s PT visits) then you will have a document that just needs minor tweaking.

Take notes on conversations (including dates and full name of the person you spoke with) at the company or doctor’s office. I learned that tip from my grandfather, a court stenographer for over 50 years: always keep track of the date, time, and name of the person you talked with. It may not be enough to prove your case, but if you can say “I spoke with (first and last name) on (date)” it lends credence to the fact that conversation took place.

Obviously, this post is not a comprehensive list of all types of conditions and how to win appeals for them. I know there are many readers who have had/will have experiences different from my own. I cannot tell you what will work for you; I can only tell you what has worked for me. I hope that by doing so and sharing some of these anecdotes you will learn something that you can apply in your own case. I realized while writing this piece over the past few weeks that there is so much to say about it. I’d like to consider this post an introduction to the topic; I will definitely revisit it again in the future.

I remember distinctly sitting in movie theaters when I was pregnant. At various points throughout the film I’d tune out the words and images and get lost in my belly, feeling each of my children squirm and wriggle and stretch. “What if this is it?” I’d think to myself. “What if I go into labor right here, right now?” And then I’d think to myself, “In just a week or two I’ll be a mother, mother to a person whose body is inside mine but whose face I have not seen, whose voice I do not know, whose skin I have not touched. I’ll be mother to this person for his or her entire life, my life will be shaped by his, and his by mine.” And those thoughts seemed incomrehensible to me at the time. Too large, too vast.

I remember distinctly sitting in movie theaters when I was pregnant. At various points throughout the film I’d tune out the words and images and get lost in my belly, feeling each of my children squirm and wriggle and stretch. “What if this is it?” I’d think to myself. “What if I go into labor right here, right now?” And then I’d think to myself, “In just a week or two I’ll be a mother, mother to a person whose body is inside mine but whose face I have not seen, whose voice I do not know, whose skin I have not touched. I’ll be mother to this person for his or her entire life, my life will be shaped by his, and his by mine.” And those thoughts seemed incomrehensible to me at the time. Too large, too vast.

Link to Twitter

Link to Twitter