October 15th, 2014 §

From the time my oldest child, Paige, was born everyone kept telling me, “Just you wait.”

From the time my oldest child, Paige, was born everyone kept telling me, “Just you wait.”

When she made it through the terrible twos without much of a tantrum everyone kept telling me, “Just you wait.”

When she made it through elementary school and a move from NYC without trouble they kept saying, “Just you wait.”

“Just you wait,” they said, “girls are drama. You got lucky before. But the teen years? Oh boy… just you wait.”

Today she prepared me a bowl of soup and brought it up to my bedroom. I was resting after my surgery to remove malignant lymph nodes and tissue for testing yesterday, the room was dark. I invited her to come snuggle with me in the big bed. We’ve never let our children sleep in our bed so they think climbing in is a big treat.

I asked her if she wanted to talk about what was going on, about my news about having metastatic breast cancer. She did.

And so it began: an hour-long talk that started with her first question, “Are you scared?”

She asked questions about genetics and risks of getting cancer to what kind of treatments I might need.

She asked me again, as if to confirm for herself, “It’s not curable, right?”

We talked about my writing, about being public with my health status, about being open and honest with her and her brothers.

I told her that yes, I was scared. I explained that my fear usually comes from the unknown, in this case just how I will respond to treatments. I told her it was okay to be scared. That it’s normal, that sometimes fear makes you brave enough to do things you don’t think you can otherwise do.

I told her that I understood that sickness could be scary, that I didn’t want her to be afraid of me as I got sicker someday. “I would never be afraid of you, Mom. I’m only afraid of cancer,” she said. My heart squeezed and thrashed and the tears flowed.

We talked about her desire to be a doctor, a surgeon. She wanted to know what all of my surgeries and treatments had done. She wanted to know the difference between cancer “stage” and “grade.” We talked about the genetics of breast cancer and discussed the BRCA-1 and 2 genes (which I do not have). We talked about hormones and their role in puberty, menopause, and cancer. She wanted to know why outcomes are so variable. How will we know if treatments are working? I told her about the importance of her monitoring her own health, how hopefully we will have better screenings down the road.

I told her that for now I want her to live her life, for our house to be as normal as it can be for as long as it can be.

I told her she should try to focus on her schoolwork, her sports, and her friends. She told me that I was more important.

I told her that eventually I might need someone to help take care of me. “I will take care of you, Mom. You’ve always taken care of us,” she said.

We talked about her brothers, ages 11 and 6 and how she was going to have to help them. And her dad too. “I’m really good with hospitals and medical things, Mom… I’m just like you.”

She said she liked that I was open about it. That people knew. She thought it was best to be honest and appreciated the offers of support she’d received from friends and adults she knows.

I told her that what we were doing, lying there talking for an hour together about this, was the most important thing we could be doing today. I told her there wasn’t anything more important to me than my family. My job is to help them deal with this. Whatever this is.

I explained that what she needed from me would likely differ from what her brothers need; she is older and each of them would have different needs along the way. It’s my job to figure that out and address it. And my husband’s job now, too. How I take the lead on this will be important.

She asked if that was a lot of pressure, to have so many people reading my words, watching what I was doing. I told her it was. I told her it was my way of trying to help people. The same way that she wants to be a doctor to help others… well, I have always tried to see if I could help in my own way. And the way we talked before about the unknown being what’s scary? Well, my writing here means it’s less mysterious. Knowledge helps. Even if the knowledge is not what you want to hear, knowing is better.

Denial won’t change the course of things, and often makes things worse.

Secrecy is bad. Sharing and supporting are what I champion. And I know that de-mystification is a constant effort. I will continue to teach my children daily. I said I hoped that somewhere in all of this she could see how important science and medicine are in my world. And that if she does decide to be a doctor that is a noble effort. She will make me proud in whatever she does. As will my boys.

The funny thing is how much better I felt after we talked. The conversation was the hardest one I’ve had. The topics are gut-wrenching. But shining the light on them, on this disease, on what happens next, is the only way I know to cope, to help, to keep going.

We talked on and on as I combed my fingers through her long hair. I stroked her smooth, soft cheek. She was giving me strength.

And what I realized about people saying I should just wait because she’s going to eventually act out:

Waiting is a luxury.

Waiting means having time.

And that’s what I want most in this world right now.

October 12th, 2014 §

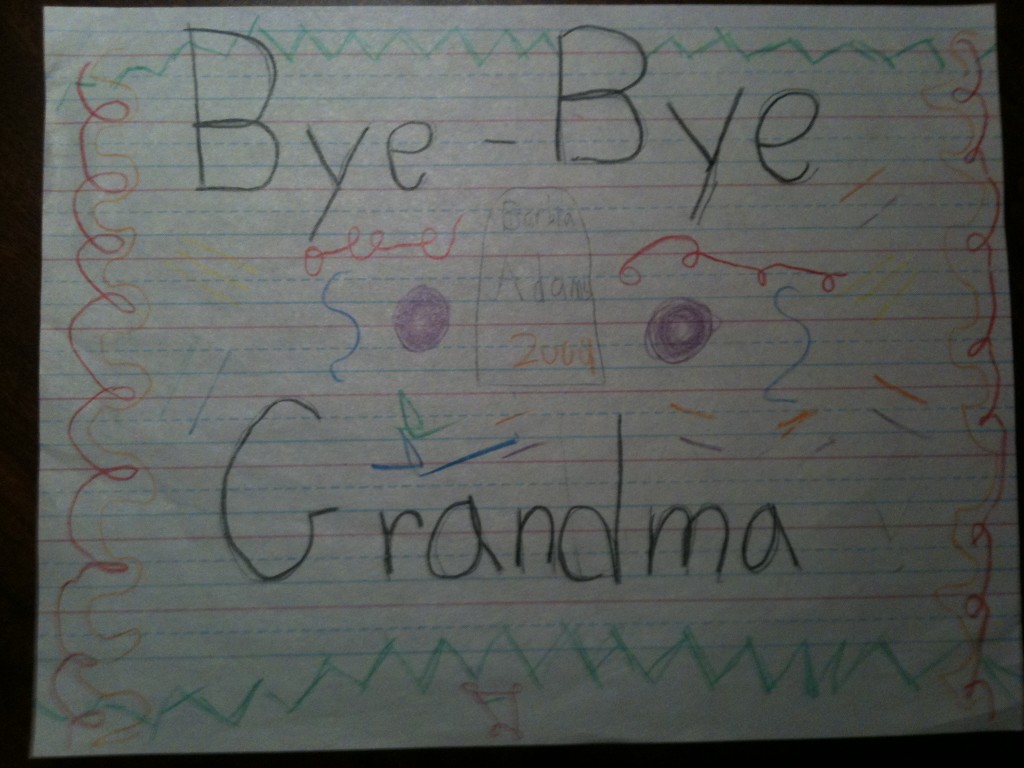

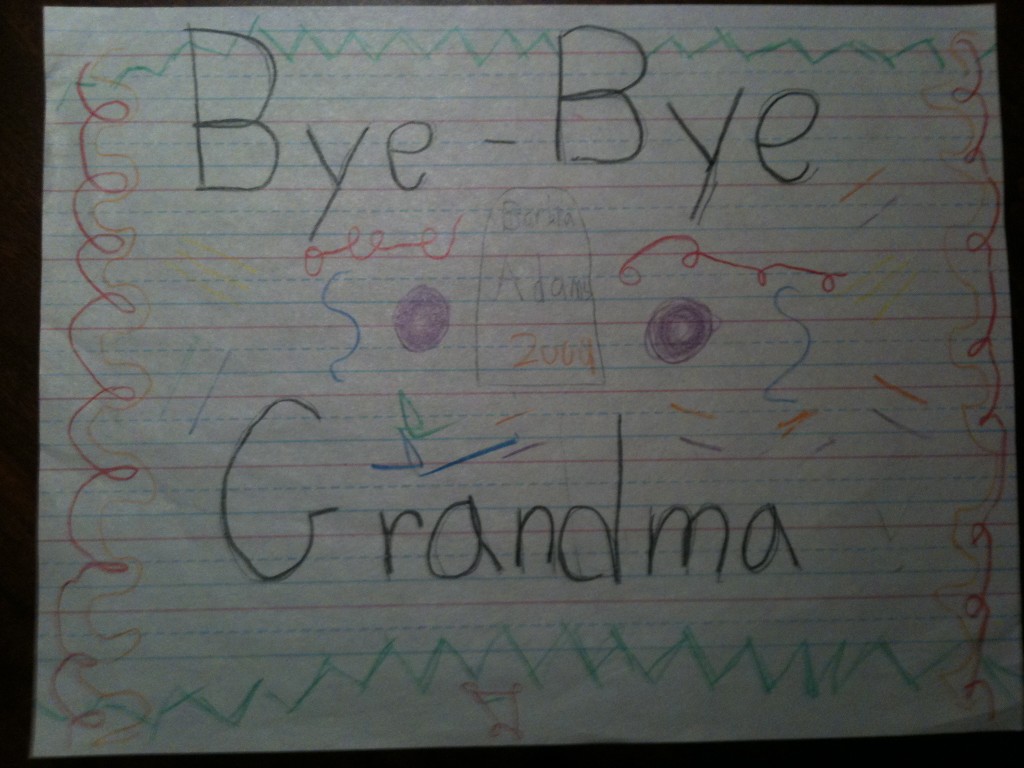

I make sure my family goes on trips without me now.

It is important that they learn to be without me.

Important that they get time away from here.

Important that they know there can be fun and joy even if I am not with them.

This is what I want.

This is what will be.

It is not easy to be the family of someone who is ill.

I know this is true.

And so I send them away to laugh, to be together, to have fun.

This is what I unselfishly demand.

In April of 2013 we all went to Florida. I didn’t know it would be our last trip together for a while. I could not focus very well. I just knew that life was not the same and it never could be. I had learned about six months earlier that I had metastatic breast cancer. I knew I would never be carefree again. I had intended to stay away from writing for that time, but on this particular day, in this moment, all I could do was realize the agony that was my situation. When I got back to the hotel room I wrote the words that had been in my head.

…………………………………………………

“Floating Away”

I sit on the beach, feel the sand’s angry texture rub my chemo feet in a way I wish it wouldn’t.

I sit on the beach, feel the sand’s angry texture rub my chemo feet in a way I wish it wouldn’t.

I watch my family in the ocean, turquoise and calm and vast.

My husband flips over, face in the water, takes some strokes out to sea.

His movement is graceful, effortless, just as it was the when I met him 22 years ago.

He was a sprinter on the college swim team then,

and while he laughs and says it doesn’t feel effortless anymore,

nor perhaps fast,

it does not matter.

In my mind’s eye he is that young man,

swimming fast,

joking with his team,

coming over to the stands to talk to me while chewing on the strap of his racing goggles.

I fall in love with him again every time I see him swim.

My three children float, bobbing in the ocean water.

I can feel the distance between us, it feels like a lifetime.

It is my family in the ocean floating away from me.

I see the quartet, I watch as an outsider.

I do this a lot lately.

I watch them from afar and think how it will be without me.

A new family unit.

Behind the big black sunglasses my tears stream down.

Suddenly Tristan is running from the water to me, across the sand.

He stands, dripping, face beaming.

“I just wanted to tell you I love you, Mama.”

I take his picture.

I capture the sweetness.

I grab him, hug him, feeling the cold ocean water on him, melding it to my hot skin.

I murmur to him what a sweet boy he is, that he must never lose that.

I send him back to the ocean, away, so I can cry harder.

By the time they return to shore I’ll have myself composed.

But my oldest immediately senses something amiss.

She mouths to me, “Are you okay?” and pantomimes tears rolling down her cheeks.

Yes, I nod.

I walk to the water’s edge to prove it.

October 10th, 2014 §

When I die don’t think you’ve lost me.

When I die don’t think you’ve lost me.

I’ll be right there with you, living on in the memories we have made.

When I die don’t say I “fought a battle.” Or “lost a battle.” Or “succumbed.”

Don’t make it sound like I didn’t try hard enough, or have the right attitude, or that I simply gave up.

When I die don’t say I “passed.”

That sounds like I walked by you in the corridor at school.

When I die tell the world what happened.

Plain and simple.

No euphemisms, no flowery language, no metaphors.

Instead, remember me and let my words live on.

Tell stories of something good I did.

Give my children a kind word. Let them know what they meant to me. That I would have stayed forever if I could.

Don’t try to comfort my children by telling them I’m an angel watching over them from heaven or that I’m in a better place:

There is no better place to me than being here with them.

They have learned about grief and they will learn more.

That is part of it all.

When I die someday just tell the truth:

I lived, I died.

The end.

October 3rd, 2014 §

It seems like you can’t rank anguish. You shouldn’t be able to “out-suffer” someone. How do you quantify misery?

It seems like you can’t rank anguish. You shouldn’t be able to “out-suffer” someone. How do you quantify misery?

And yet, somehow we do.

“My problems are nowhere near as bad as yours are.”

“I feel terrible complaining to you about it when you are going through so much yourself.”

I hear these types of comments all the time.

I make these types of comments all the time.

Placing ourselves in a hierarchy of pain and suffering serves to ground us; no matter how bad our situation is, there’s comfort in knowing there is always someone who has it worse.

Like being on a really, really long line at the movies or at airport security, as long as there is someone behind you, it somehow seems better.

Hospitals use a pain rating scale: “On a scale of 1 to 10, how bad is your pain?” When our son Colin was in the hospital for 9 days with a ruptured appendix, they asked him to rate his pain. I was intrigued at his difficulty in answering the question. At the time he was 5 years old and didn’t understand what they wanted him to do. Colin didn’t understand the concept of comparing one level of pain to another; His abdomen hurt… that’s all he knew. He used a binary scale to assess his pain: did it hurt or not? As adults we know better: pain is not a yes-or-no question. Rather, there can be levels, ranking, quantification, and comparisons.

These mental exercises are necessary to keep us going through hard times, no matter what type. Before I got cancer, cancer was a “go-to” negative reference point. I mean, how many times had I, and everyone I know, thought or said, “I’ve got health problems, but at least it’s not cancer”?

I had done that a lot.

A benign lump needs to come out? At least it’s not cancer.

A mole needs to be removed? At least it’s not cancer.

My son has hand and neck deformities and a cyst in his spinal column? At least it’s not cancer.

Then one day it was cancer.

So what could I pacify myself with?

At least it’s not terminal.

At least they can remove the body parts the cancer is in.

At least this debilitating treatment will be temporary and I have the possibility of returning to a normal life again.

Then there was the big one: at least it’s happening to me and not my child.

And when I found out that my cancer had metastasized, I could not calm myself with those comforting refrains anymore.

Now it is terminal.

Now they can’t remove the body parts it is in.

Now the debilitating treatments are permanent and I don’t have the possibility of returning to anything close to a normal life again.

I have often said I have hated becoming anyone’s negative reference point. “At least I’m not her” people now often think of me. I always thought that meant they pitied me. I didn’t want that. But now I realize that it is okay for people to be glad they haven’t walked in my shoes– in reality, that’s what I want. I don’t want anyone to be where I have been and where I am; I’d like to be the lightning rod that keeps other people safe. But we all know it doesn’t work like that.

Denial has never worked for me.

Denial doesn’t kill cancer.

I still believe it could be worse.

I know that is true.

And so, for today, I focus on the fact that I’m not the last one on line.

On the really challenging days sometimes that knowledge is all I have.

And on those days, that knowledge is enough.

September 18th, 2014 §

I know I’m supposed to stop and smell the roses

I know I’m supposed to stop and smell the roses

But life is going to keep moving on

Without me.

So maybe instead you should just

Keep the motor running,

Let me hop out for just a moment.

While you’re not looking

I might just try to run.

But I realize you’re not paying attention any more…

I’m taking too long,

So I will linger a while,

Taking in the glory,

Before the last breath.

August 22nd, 2014 §

Grow up faster,

Grow up faster,

Need me less,

Reach the sky,

Stand up tall.

Make time go,

Speed it up,

Get it done,

Don’t look back.

Hear my voice,

Feel my embrace,

Know I tried,

Look straight ahead.

Keep forging,

Thinking,

Feeling.

There is no choice,

This world is all there is,

Make it last.

Ours will be far shorter a time than it should be:

Years compressed into months, days, hours, minutes.

It will never be long enough,

It simply could never be enough time with you.

August 4th, 2014 §

They were already seated when we arrived, a sea of white sitting cramped.

They were already seated when we arrived, a sea of white sitting cramped.

Mostly couples, though some were in girl groups.

They didn’t rise when we needed to pass by.

Clearly that effort would be too much.

I know how that feels.

Almost all wore glasses, most eventually pulled out bags of snacks or sucking candies.

No one texted or emailed or checked the time on a phone.

They all had small watches on their wrists for that.

In front of me a man had a bandage on the top of his head, white gauze perched amidst his silver hair, a good head of it.

I decided a funny looking mole, irregular in shape, had lain there recently; his wife pressed him to go see the dermatologist to have it checked.

The two looked out for each other, you see, having been together so long.

The air was still and thick and choked me as the minutes wore on.

I could see the veins protruding on the back of their hands, the wrinkles, the hunched shoulders.

We were the youngest there.

And while I felt more like them in many ways, closer to the end than to the beginning, I realize I am an outsider in every group.

There are few like me.

My hair won’t get that white, you see,

My hands won’t be rewarded with that saggy skin.

I won’t be privileged enough to see him go bald.

It will always be “in sickness” now.

The lights finally went down and I tried to forget.

But my body and mind do not ever let me.

How jealous I was of those elderly people crowded into a movie theater on an August Sunday afternoon.

July 9th, 2014 §

Now that all three of our children are at sleep away camp I get asked a lot “what I’m doing with all of my free time” and “what fun things I have planned.” Clearly what people think life is like for me are a bit skewed. I have nothing planned. I can’t travel and haven’t been able to take a trip for over a year. I’ve missed family celebrations, holidays, and get-togethers. I’ve eschewed visits from family and friends because I’m not well enough. What others consider “free time” is recovery from chemotherapy and struggling to do day-to-day functioning including the many medical appointments. Being able to make it out for a coffee date is a thrill and isn’t possible many days. Most of the rest of the time my “free time” is spent in bed fighting nausea or fatigue or pain or other side effects.

Now that all three of our children are at sleep away camp I get asked a lot “what I’m doing with all of my free time” and “what fun things I have planned.” Clearly what people think life is like for me are a bit skewed. I have nothing planned. I can’t travel and haven’t been able to take a trip for over a year. I’ve missed family celebrations, holidays, and get-togethers. I’ve eschewed visits from family and friends because I’m not well enough. What others consider “free time” is recovery from chemotherapy and struggling to do day-to-day functioning including the many medical appointments. Being able to make it out for a coffee date is a thrill and isn’t possible many days. Most of the rest of the time my “free time” is spent in bed fighting nausea or fatigue or pain or other side effects.

For the last few weeks my blood counts were sliding and I couldn’t do anything without huffing and puffing in a much more severe way than usual. I struggled to bend over to pick something off the floor without needing to sit down to catch my breath. My hemoglobin levels had been hovering around 8.2 for months and I pushed through but they dropped to 7.2 and by then it seemed I needed a boost to be functional. Ten days ago I received two units of red cells in a transfusion that because of some problems with the samples and testing and a five hour infusion ended up being a ten hour marathon day. It was so worth it. Red counts came up within days and I felt better starting about 24 hours after receiving the cells and that continued to increase within two to three days. My platelets were also very low at 24 but regenerated on their own (low platelets are a predictable result of this chemo regimen) and I was able to avoid a transfusion of those. This was, by the way, the first time I had ever had a blood transfusion in my life.

I had chemo yesterday: Carboplatin and Gemzar cycle #6 (that means I’ve had 6 infusions of Carboplatin and 11 of Gemzar so far). Starting now, but especially with cycle 7 and every time after that, there is a risk (reported at 27% for round 7, here is an article for anyone interested) of an anaphylactic reaction to the Carboplatin (and the other platinum-based chemotherapies like it). We are being conservative and premedicating with drugs that will hopefully help blunt or avoid this type of reaction altogether. There isn’t any reliable way to predict if it will happen to any individual patient. I did have a reaction to Taxol when I received it in the metastatic setting (after not having a reaction the first time I had 4 cycles of it seven years ago) but that is not a reliable indicator of a reaction to platinum-baed drugs.

It will be time for a scan soon I think, we are watching my tumor markers which have dropped consistently in the last few months which is fantastic but on yesterday’s test just stabilized without a drop. We’ll have to see if this is just stabilization (fine) or if this is the start of the chemo losing its effect. It is unsettling to think about losing another chemo combination that has been working, even though it’s a tough regimen to tolerate.

My voice has returned to almost normal unless I use it on the phone or talk a lot. With the kids gone I really am not talking much. I had an extra five days off chemo because my oncologist was on vacation and that allowed me to get things done I usually don’t have enough rebound time to do. The transfusion timing helped too.

I haven’t been outside much, the humidity and heat have been too oppressive for me, but I am hopeful it will break soon. I do try to make it to the beach once a week to get a change of scenery.

I haven’t been outside much, the humidity and heat have been too oppressive for me, but I am hopeful it will break soon. I do try to make it to the beach once a week to get a change of scenery.

We will get to see the kids this weekend and I can’t wait to hug them and hear all of their stories before they go back. They love camp, always have. They look forward to it year-round and now that they all go it’s great they can share these stories and experiences (they are 15, 12, and 8. Last year the youngest begged to go for a week to try it out. We said yes, knowing his siblings would be there and he would have a blast. Five days in he called in tears, begging to stay. That repeated every week until after a month we said it was time to come home!).

Some may wonder why, at this time, I let them go instead of keeping them home with me. I do it because it’s not about me. It’s about them. It’s something they love. It’s an important routine, tradition (this is the sixth year for the oldest). In my eyes, it’s important that they have a change of scenery, freedom to be kids, get away from the ways my cancer and its chronic treatment limit what I can do, and therefore what they can do. It’s a gift I can give them and I also feel it reassures them that I am doing better than I was a few months ago. This is important.

I love having them away from electronics, away from wondering if asking me to take them somewhere or do something with them will be “too much” or “bothering me” which I know the older ones are always concerned with. I want them to be with friends old and new, having fun with young and energetic counselors, trying new things. There are so many (most/all) physical activities I cannot do with them that they can do there. So many new games to play, achievements, laughs, experiences. I never hesitated when they were ready to sign up last October for this summer. I knew that no matter what, they needed and deserved it. On the left is my favorite photo from camp so far: Tristan getting hooked in to try rock wall climbing for the first time. It makes me laugh every time I look at that facial expression!

I love having them away from electronics, away from wondering if asking me to take them somewhere or do something with them will be “too much” or “bothering me” which I know the older ones are always concerned with. I want them to be with friends old and new, having fun with young and energetic counselors, trying new things. There are so many (most/all) physical activities I cannot do with them that they can do there. So many new games to play, achievements, laughs, experiences. I never hesitated when they were ready to sign up last October for this summer. I knew that no matter what, they needed and deserved it. On the left is my favorite photo from camp so far: Tristan getting hooked in to try rock wall climbing for the first time. It makes me laugh every time I look at that facial expression!

That doesn’t mean it’s easy for us to be apart. We are very close. Especially the older kids worry about me I am sure. But I stay in touch by email, will see them on visiting days, and I send them weekly care packages.

But the truth is that separation is good. It’s a selfless act for me to teach them how to to be without me. One of the most important things, in my mind. Coddling them and making them stay home is not what I feel is best for them right now. It is part of our job as parents to teach our children how to be independent, how to solve problems on their own, how to go off in the world without us for whatever reason. I will always want more time with them. It will never be enough for me. But this is my old age. I must teach them as many lessons as I can, while I can, for as long as I can. And that is true for everyone, but of course I have not only the urgency to do it NOW but also I have no idea how long I have and will likely be debilitated in some form until that time comes.

Yes, it’s true no one knows how long they have to live. But those diagnosed with a terminal disease know what is most likely to kill them. And that their time is not just going to be shortened, but consumed daily with the treatment and effects of that disease. It’s not having a normal, healthy life that is relatively good and healthy until a sudden accident happens. It’s just not the same as the general worries of growing older or aches and pains. It’s never-ending. I don’t get to count down how many chemotherapy (or other treatment) sessions until I’m done this time. Being done will mean there is nothing left for me to try. Anyone who has had chemo or radiation or some other type of therapy knows how important it is to have an endpoint, a countdown. Knowing that will never happen (and in fact what you’re really hoping for is a lot of them, because that means you still have options) is one of the mental struggles each week, since it isn’t just spending one day a week getting chemo, it’s how it makes you feel each day after that.

My hair is growing slowly back on this current combo. I know many people mistakenly think this means I’m “better.” I do like that soon I won’t be covering my head and that means I can be more invisible in public. But I also know how many comments I get on the occasions I have done it that people think I am done with chemo or all better. Not all chemotherapies cause hair to come out. My hair will come and go numerous times by the time we are done with this. Its presence or absence only indicates something about which chemo I’m on, not its success or failure.

Someone on Twitter asked for my piece on what to say and how to be a friend to someone who has cancer/serious illness. Here is a link for anyone that missed it and is interested (it’s too long to include the text in this post).

Also, I am including two posts from last year at this time. One on the eve of the kids’ departure for camp and one written while they were away. Of course I was doing even better than I am now, my thoughts were similar, but not as urgent, strong, painful as they have been the last seven months.

I’ll post again with an update if there is anything to report on change in treatment, scan results, etc. For now we stay the course which is not easy, but is the best possible choice of the options I have right now. And that’s the best I can do.

I appreciate the support, as always!

…………………………………………….

In these last remaining hours (Camp) original post here

In these last remaining hours

Before my children disappear

One,

Two,

Three…

In these last remaining hours before they go and spread their wings again,

Leave this nest,

I miss them already.

I put the dinner pots and pans away.

Wipe the crumbs from the table,

Load the dishwasher,

Play fetch with the dog.

I sit in the garden,

Listen to the wind in the trees,

The birds settling down before nightfall,

As we settle, too.

I tuck them in one last time,

Hear their doors click shut.

One,

Two,

Three.

Tomorrow night there will be no mess to clean,

No yelling upstairs that the TV has been left on again,

No trunks piled high with carefully labeled belongings in the dining room.

I will cry, I know.

Not because I am sad that they are going– no, that gives me great joy.

Children being children.

Forgetting stress at home and doing new and varied things.

I cheer their independence.

I will cry because I know they will always need me somehow and I just wish I could be there for them to outgrow

by choice,

by time,

by age.

I hear the mother bird in the tree calling out.

I don’t know to whom.

I will be like that tomorrow,

calling out,

with no child to hear.

……………………………………………………….

Like dollhouse rooms left abandoned (original post here)

Like dollhouse rooms left abandoned,

The rooms stay tidy:

Beds made tight,

Pillows square,

Hampers empty.

It’s been one week since the children left for camp.

Littlest Tristan was due back yesterday but a few days ago he said he was having so much fun he wanted to stay another week.

I realized this week that after being sick for the previous two that I needed this time to catch up, to rest, to regroup.

I miss them but am so glad they are having fun doing what they love.

I pack up care packages,

write letters,

wake in the middle of the night and mentally picture our children sleeping in cabin beds.

Our dog Lucy follows me, sleeps in my room now, not Paige’s.

She doesn’t want to be alone and stays within feet of me every moment.

I tell her it’s okay:

The kids will come back.

The rooms will get messy again.

There will be crumbs dropped at the dinner table and car rides galore.

Paige and Colin and Tristan will come back tired and dirty and happy.

They will come back.

They will.

That is the key.

I think of absence like a hole:

How different it is when it’s temporary and filled with happiness,

Rather than when that hole is a pit of grief. Of ache. Of loss.

The way it will someday be for them.

March 4th, 2014 §

Hi everyone, an update to briefly say hello since my posts are still infrequent. It’s been about three months now since this particular acute metastatic breast cancer episode started. First I was stuck at home in pain with tumors in my spine and hips before and during the holidays. Then I was in the hospital for three weeks at the start of 2014 getting pain under control and having two weeks of radiation. Now I’ve been home for another six weeks since leaving the hospital.

Hi everyone, an update to briefly say hello since my posts are still infrequent. It’s been about three months now since this particular acute metastatic breast cancer episode started. First I was stuck at home in pain with tumors in my spine and hips before and during the holidays. Then I was in the hospital for three weeks at the start of 2014 getting pain under control and having two weeks of radiation. Now I’ve been home for another six weeks since leaving the hospital.

After such a long period of time many people will start to assume you “must be back to normal by now.” Each day they anxiously wait for news that someone “feels better.” It doesn’t work like that all the time, just the way with metastatic cancer you don’t “beat it.” A good day or two may come, but they are often followed by a bad one, or two, or three. Add chemo to the mix and you start to realize the good days are relative and elusive in incurable cancer. Support is always so appreciated as the days, weeks, months go by. It’s friendship for the duration.

There are many situations where isolation may be a real danger including examples of infertility, chronic illness, and grief. Those who must deal with these problems start to feel isolated. Additionally, they may start to actively separate from others when they feel that life is just moving on without them. As time goes on, they may hesitate to talk about their problems because they fear that friends will have grown weary of hearing about it/ still can’t relate to it. More and more, they keep these things to themselves. This leads both to further isolation and also the faulty notion from their friends that the person is “over it.”

The truth is that it’s very hard when difficult situations of all kinds linger. I think we all do better when tough times are brief. Being in one of these situations has shown me the depth to which this is the case.

Today I had to miss Tristan’s Spring music show at school. It broke my heart to tell him I couldn’t attend. They were able to videotape it and I know we will watch it together and have a special time doing that. If it were just one thing it would be different. But as any parent can imagine, saying, “I’m so sorry but I can’t…” again and again for months is difficult. The truth is that if I knew it were temporary it would be easier. But I know that there will be more and more things I can’t do with the kids. And that’s what weighs on me: this thing is part of a whole.

I tried driving last weekend but unfortunately, for now, the verdict is that I am still unable to do more than go to the bus stop at the end of the street if needed. So I continue to be housebound.

I’m working with my doctors to adjust my medications and try to manage the vertigo, sedation and pain. I am using less pain medicine (hooray) but unfortunately I still feel so rotten I sometimes can’t get out of bed and most often can’t go anywhere except to chemo. It is a cruel balance. This weekend I was stuck in bed for three days. It saddens me to lose so much time.

I still long to write here more. I miss the creative part of my brain working the way it used to. I miss poetry and photography and so many things. I will bring them back though! The orchid photo above is one I took in the kitchen this week. My friend Alex brought me lunch and a beautiful potted orchid. I even ordered daffodils with my groceries this week to remind myself of the garden outside and what’s waiting under this snow.

Winter break at school came and went. I know it’s a very busy time for everyone as Spring approaches. It’s hard to see life outside passing me by while I wait for Spring so I can at least get fresh air here at home. It has continued to be cold and wintery over the past few weeks. If you’re able to be outside today doing anything: errands, standing at the bus stop, or waiting the train platform on your way to work: think for a moment what it would feel like not to do any of that for three months. It’s a very long time. Mundane things can be sweet when viewed in a different light.

I am so grateful for the offers of help and meals that continue to come. Let me assure you they are so needed and appreciated. I will have chemo again this week. In two weeks’ time the plan is to do scans to see if there is any visible evidence about whether radiation and chemo have shrunk the cancer.

My daily reminder: Find a bit of beauty in the world today. Share it. If you can’t find it, create it. Some days this may be hard to do. Persevere.

In case you need a bit of beauty I will leave you with one of mine, a good laugh this week from Tristan. With a very serious expression on his face he says to me quietly from the dinner table, “Mom, I have something to tell you and you’re not going to like it. It’s something I learned. I was reading it in a book. But I think you will be upset. The book was about Albert Einstein. It said that for a while he didn’t want to go to school. He didn’t want to learn things in school that they wanted him to learn. He just wanted to learn what he wanted to learn. He stayed home for a while and didn’t go to school. See? I think you would not think that was very good that Albert Einstein didn’t want to go to school.”

November 24th, 2013 §

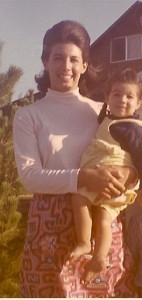

I could not have known at that time the path my life would take. I could not have known how my words were reaching into the future, knowingly, achingly.

I could not have known at that time the path my life would take. I could not have known how my words were reaching into the future, knowingly, achingly.

I originally wrote about Katie Rosman’s book If You Knew Suzy in 2010. The blogpost was written before my diagnosis with metastatic breast cancer but years after my diagnosis of stage II breast cancer. My fears, articulated below, of my cancer returning and taking me from my family have now come true. It is interesting to read my words now through this new life lens.

Katie and I have grown so close since I first wrote about her book, her mother, and their effect on me. Our friendship runs deep. I treasure Katie’s thoughtfulness, her compassion, her devotion to her family, her laugh, and yes, I’ll say it: I am very jealous of her curly hair and ability to do handstands.

………………………..

November is Lung Cancer Awareness Month. Misinformation and stigma are still linked with lung cancer.

I get asked all the time, “Why do you think you got cancer so young the first time? Why do you think it metastasized?” I think people are searching desperately for identifiable reasons so they can feel “safe” from the fate I have (Clearly she must have done something to be seeing it once again, right? That won’t happen to me, right? If I just eat this or drink that it won’t happen to me, right?).

There is one question almost universally asked of those diagnosed with lung cancer: “Smoker?” There are many risk factors for lung cancer that have nothing to do with smoking. In fact, I only learned after having an oophorectomy in 2008 that surgically-induced menopause significantly increases the risk of lung cancer (one paper here).

Yes, current smokers are those most likely to be diagnosed with lung cancer. But there are increasing diagnoses of those who have never smoked and many who stopped decades ago. We need much more research into the spectrum of causes of lung cancer (including radon and asbestos exposure) and effective treatments. The stigma associated with it, however, is a barrier to raising money for research compared with other cancers. It is the deadliest cancer; more than 25% of cancer deaths are from lung cancer (more than from colon, breast, and prostate cancer combined) yet receives only a fraction of research funding.

I wanted to share this post again during Lung Cancer Awareness Month to highlight one life. Writing is powerful. Across time and space, without ever having heard each other’s voices or shaken each other’s hand, I have learned so much from Suzy.

Katie’s mother, Suzy Rosin, died from lung cancer.

……………………….

There comes a point in your life when you realize that your parents are people too. Not just chaffeurs, laundresses, baseball-catchers, etc.– but people. And when that happens, it is a lightbulb moment, a moment in which a parent’s humanity, flaws, and individuality come into focus.

If you are lucky, like I am, you get a window into that world via an adult relationship with your parents. In this domain you start to learn more about them; you see them through the eyes of their friends, their employer, their spouse, and their other children.

Yesterday I sat transfixed reading Katherine Rosman’s book If You Knew Suzy: A Mother, A Daughter, A Reporter’s Notebook cover to cover. The book arrived at noon and at 11:00 last night I shut the back cover and went to sleep. But by the middle of the night I was up again, thinking about it.

I had read an excerpt of the book in a magazine and had already been following Katie on Twitter. I knew this was going to be a powerful book for me, and I was right. Katie is a columnist for The Wall Street Journal and went on a mission to learn about her mother after her mother died in 2005 from lung cancer. In an attempt to construct a completed puzzle of who her mother was, Katie travels around the country to talk with those who knew her mother: a golf caddy, some of her Pilates students, her doctors, and even people who interacted with Suzy via Ebay when she started buying up decorative glass after her diagnosis.

Katie learns a lot about her mother; she is able to round out the picture of who her mother was as a friend, an inspiration, a wife, a mother, a strong and humorous woman with an intense, fighting spirit. These revelations sit amidst the narrative of Katie’s experience watching her mother going through treatment in both Arizona and New York, ultimately dying at home one night while Katie and some family members are asleep in another room.

I teared up many times during my afternoon getting to know not only Suzy, but also Katie and her sister Lizzie. There were so many parts of the book that affected me. The main themes that really had the mental gears going were those of fear, regret, control, and wonder.

I fear that what happened to Suzy will happen to me:

my cancer will return.

I will have to leave the ones I love.

I will go “unknown.”

My children and my spouse will have to care for me.

My needs will impinge on their worlds.

The day-to-day caretaking will overshadow my life, and who I was.

I will die before I have done all that I want to do, see all that I want to see.

As I read the book I realized the tribute Katie has created to her mother. As a mother of three children myself, I am so sad that Suzy did not live to see this accomplishment (of course, it was Suzy’s death that spurred the project, so it is an inherent Catch-22). Suzy loved to brag about Katie’s accomplishments; I can only imagine if she could have walked around her daily life bragging that her daughter had written a book about her… and a loving one at that.

Rosman has not been without critics as she went on this fact-finding mission in true reporter-style. One dinner party guest she talked with said, ” … you really have no way of knowing what, if anything, any of your discoveries signify.” True: I wondered as others have, where Suzy’s dearest friends were… but where is the mystery in that? To me, Rosman’s book is “significant” (in the words of the guest) because it shows how it is often those with whom we are only tangentially connected, those with whom we may have a unidimensional relationship (a golf caddy, an Ebay seller, a Pilates student) may be the ones we confide in the most. For example, while Katie was researching, she found that her mother had talked with relative strangers about her fear of dying, but rarely (if ever) had extended conversations about the topic with her own children.

It’s precisely the fact that some people find it easier to tell the stranger next to them on the airplane things that they conceal from their own family that makes Katie’s story so accessible. What do her discoveries signify? For me it was less about the details Katie learned about her mother. For me, the story of her mother’s death, the process of dying, the resilient spirit that refuses to give in, the ways in which our health care system and doctors think about and react to patients’ physical and emotional needs– all of these are significant. The things left unsaid as a woman dies of cancer, the people she leaves behind who mourn her loss, the way one person can affect the lives of others in a unique way… these are things that are “significant.”

I woke up in the middle of the night thinking about the book. My head spun with all of the emotions it raised in me. I think that part of the reason writing has become so important to me is precisely because I do realize that we can die at any moment. And if you don’t have an author in the family who might undertake an enormous project as Katie did, where will that explanation of who you were — what you thought — come from?

Is my writing an extension of my desire to control things when cancer has taken away so much of this ability?

Is part of the reason I write an attempt to document my thoughts, my perspective for after I am gone… am I, in a smaller way, trying to do for myself what Katie did for her mother?

If I don’t do it, who will do it for me?

And in my odd way of thinking, am I trying to save anyone the considerable effort of having to work to figure out who I was– deep down?

[My original blog had] the title “You’d Never Know”: I am telling you things about myself, my worldview, and my life, that you would otherwise have no knowledge of. One of the things people say to me all the time is, “You’d never know to look at you that you had cancer.” After hearing this comment repeatedly I realized that much of our lives are like that:

If we don’t tell someone — share our feelings and experiences — are our lives the proverbial trees falling (unheard) in the forest?

What if you die without being truly understood?

Would that be a life wasted?

If you don’t say things for yourself can you count on others to express them for you?

Further, can anyone really know anyone else in her entirety?

After a loved one dies, there always seems to be at least one mystery person: an individual contacts the family by email, phone, or in person to say, “I knew her: this is how I knew her, this is what I remember about her, and this is what she meant to me.” I know that this happened when Barbara (my beloved mother-in-law) died suddenly in 2009. There are stories to be told, memories to be shared. The living gain knowledge about their loved one. Most often, I think families find these insights comforting and informative.

Katie did the work: she’s made a tribute to her mother that will endure not only in its documentation of the person her mother was (and she was quite a character!) but also in sharing her with all of us. Even after her death, Suzy has the lovely ability to inspire, to entertain, to be present.

I could talk more about the book, Katie’s wonderful writing, and cancer, but I would rather you read it for yourself. I’m still processing it all, making sense of this disease and how it affects families, and being sad that Katie’s children didn’t get to know their grandmother. Katie did have the joy of telling her mother she was pregnant with her first child, but Suzy did not live long enough to see her grandson born. In a heartwarming gesture, Katie names her son Ariel, derived from Suzy’s Hebrew name Ariella Chaya.

I thank Katie for sharing her mother with me, with us. As a writer I learned a lot from reading this book. I had said in years prior that “we don’t need another memoir.” I was wrong. That’s like saying, “I don’t need to meet anyone new. I don’t need another friend.” Truth is, there are many special people. Katie and Suzy Rosman are two of them.

November 6th, 2013 §

Even when I am alone

Even when I am alone

I teeter precariously over the right hand side of the bed.

On my left shoulder when I can,

When the pain is bearable,

When I can settle in for the night.

I still approach the precipice

Rather than opt for the safety of the middle place.

I act as if he is there with me

Taking space

And I, trying to make room,

Move to outer orbit,

As if that extra inch or two would matter.

Even on the occasions I am alone

I pretend as if I am not.

I go to places in my mind,

Wondering what it will be like

When that opposite side of the bed is empty

For him

And he teeters precariously near the edge unnecessarily,

Without me there to take up space.

September 29th, 2013 §

With great sadness I announce that Jen Smith, featured in an interview here less than a month ago, died yesterday (September 28, 2013) at the age of 36 from metastatic breast cancer.

With great sadness I announce that Jen Smith, featured in an interview here less than a month ago, died yesterday (September 28, 2013) at the age of 36 from metastatic breast cancer.

Readers who receive these posts by email may not have had a working video link to see a 2 minute video of Jen and her son that was included with that interview. I am including a link to my original post here so you can either read the post if you missed it, re-read it, or just go to watch the video which appears at the bottom. I promise it is worth two minutes of your time. It makes me smile and cry in equal measure every time I watch it. It also tells the story of how Jen found the tagline “Live Legendary.”

The obituary the family posted appears here and you can read how much Jen accomplished in her too-short life. I wish I had known her longer; I am jealous of her friends and family who did.

Over the past few weeks we texted. Some days I just texted her to tell her I was thinking of her. Some days I would get a reply as to how she was doing. Some days I received no reply. Those were hard days as I worried so much about her, knowing she was about to die. I continued to text her almost daily in the last two weeks even when there was no response. My last text to her said, in part, “I cannot help myself from saying I love you for as many days as you are here to hear it.” When you have stage IV breast cancer you bond quickly with others who have it too. I do not know if she read that message.

Jen and I spent the last few months having very serious conversations about life and death. I wish we could have been two friends talking about other topics instead. But I am gratified that we could talk openly about some of the things were on her mind the most as she reached the end of her life.

My condolences to her friends and family including the light of her life, her sweet son, Corbin.

September 5th, 2013 §

I don’t remember exactly when Jen Smith (@sinclair319) and I first connected on Twitter but we definitely hit it off: two straight-talkers with metastatic breast cancer, both determined to do what we could to live as long as we could while educating others about the day-to-day reality of living and parenting with a stage 4 diagnosis. Jen had already been doing it for years, and I have always appreciated the guidance she gave when I was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer in 2012.

I don’t remember exactly when Jen Smith (@sinclair319) and I first connected on Twitter but we definitely hit it off: two straight-talkers with metastatic breast cancer, both determined to do what we could to live as long as we could while educating others about the day-to-day reality of living and parenting with a stage 4 diagnosis. Jen had already been doing it for years, and I have always appreciated the guidance she gave when I was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer in 2012.

Jen and I are direct about our shared goals (she has a son, Corbin, who is 6. He’s about the cutest boy you will ever see. The photo above was taken a few months ago). Some of our goals: be honest about cancer with our children in an age-appropriate way, be public about the reality of parenting with incurable cancer, teach independence and joy to our children and let them know these are important to experience even after we are gone, and finally, to live life to the fullest even while undergoing difficult and often debilitating treatments for the rest of our lives.

Jen was diagnosed with at age 30. I encourage you to visit her website www.livinglegendary.org to learn more about her story and her writing (her two books are titled Learning to Live Legendary and What You Might Not Know: My Life as a Stage IV Cancer Patient).

The sad reality of metastatic breast cancer is that it kills. In fact, it’s the only kind of breast cancer that can kill.

Jen is now dying. She has entered hospice after being told in late July that no other treatment options were available.

I have few ways to help Jen in her remaining time alive but one way I thought about helping her was to share her story and her spirit with my readers. I asked Jen to answer some questions for me about two weeks ago and she graciously accepted. I know that today she would not be able to spend the time and energy doing this, so I really treasure the words that she has written.

………….

Lisa: First, I want to refer to a line in your book What You Might Not Know. You write that when your friend Erin was dying you panicked. You asked, “Would others feel this same panic when I was dying?”

I would like to tell you that right now, in this moment, the answer is yes. We feel the panic. I feel it acutely. And the helplessness.

Jen: The difference was Erin just had palliative surgery to alleviate her neck pain. She was supposed to heal from that, then go on for more treatment. But, during recovery at home, she became short of breath, begged her mom to call 911. By the time they got her to the hospital, they were able to keep her sedated until her husband flew in.

I’ve watched many friends die, and the “shocking” ones like this one (and the one who just went to have a blood transfusion, then had a clot thrown in her lung and kill her) often offer a different kind of grief compared to those who go on hospice and you have “warning” that their life is coming to an end. You can brace for the looming grief.

Lisa: As an introduction, can you please tell readers what your current health is today (August 17, 2013) and why you have entered hospice. Are you currently receiving any treatment? Do you receive palliative care? Most people think of hospice as something for the last week or two of life. If you would, please share what hospice will provide for you now and going forward as you move closer to death. Do you encourage people to get involved with them sooner rather than later?

Jen: After nearly 6 years of treatment for breast cancer, on July 31st, 2013, my doctor said, “I’m sorry, we’re out of options and it’s time to refer you to hospice.”

I’ve watched a lot of friends die from this vile disease. I’ve always thought, “When hospice gets involved, I hope I go quick, in a matter of hours or days.” Now, after being on hospice for over 2 weeks, I have a different perspective. Hospice is all about comfort care…what can be done to make the patient more comfortable? While on hospice you are not allowed to receive any treatment that would be considered actively trying to kill the cancer cells (i.e., chemo). But, hospice often goes hand-in-hand with palliative care which is about relieving the pain and stress from a serious illness.

I have drains in my lungs which drain out the fluid which has built up due to the amount of cancer present. This is palliative care. It isn’t going to stop the cancer from progressing, but it is going to enable to breathe easier. When my lungs are full of fluid (sometimes close to a liter per side) my oxygen intake is pretty minimal. Because of this, my heart has to work harder to pump out that oxygen to my body. With my heart working so hard, my whole body is tired. Being able to drain my lungs takes care of the shortness of breath issue and also gives me a bit more energy since my heart isn’t working as hard.

Right now I meet with hospice weekly. I got to decide the frequency. I’m still fairly independent; I’m not confined to my house or bed. As the disease progresses, I expect that I will meet with hospice more often. Although they only visit once a week, I speak with them almost daily. They are in charge of reordering any of my supplies (i.e. lung drain kits) and refills of medication. It’s great being able to call, tell them what you need, then it magically shows up at my front door. Hospice is like a good friend, not the enemy. I’d highly encourage readers to consider their services as soon as necessary.

In full disclosure, my mom has taken FMLA time and is staying with us (I’m a single mom to a 6 1/2 year old boy). While I’m still independent, I’m able to be that way because my mom is helping with all the behind the scenes stuff. Laundry, groceries, cooking, cleaning, etc. This way I’m able to conserve my energy and use it with my son.

Lisa: You have a beautiful son, Corbin, who is about to start 1st grade. I know when you were first diagnosed with cancer at age 30 and then with metastatic cancer only 3 months after completing your original chemotherapy you set a goal of living to see him enter kindergarten. What does the advent of school mean for you emotionally now that the first goal was achieved?

Jen: Correct, I made the goal of seeing him start kindergarten when he was almost 2. I knew the statistics were against this, but it also gave me a very concrete goal. Of course I had short-term goals along the way, but this was always the ultimate goal.

Last year when I took him to his first day of kindergarten, I was excited, thrilled, and so very thankful that I got to watch him walk in the front doors. This year will be different emotionally.

In early August we learned who his teacher was. We learned his best friend would be in his class in addition to many of his friends from kindergarten. My son, like many his age, thrives on consistency and structure. I am divorced and his father lives in a town about 20 minutes away.

When I was referred to hospice, I decided that I would start my son at the school in his father’s district. I figured it was one less transition he would go through at the time of my death. So next week, when I take him to his first day at his new school, it will be a mixture of emotion. I’m so grateful that I’m able to see him start another year, yet heartbroken that him starting this school will be the first of many, many changes for him.

Lisa: How has your relationship with your physicians changed throughout the last six years with metastatic disease? And now that you have been told you are at the end of your life?

Jen: I’ve had the same primary oncologist who has always been in favor of 2nd opinions. I joke that I’ve become a hospital hussy going for 2nd, 3rd, 4th and even 5th opinions. But, my primary oncologist has always been my “go-to” person. My oncologist has been in practice for 25+ years, so he is good at keeping the doctor/patient relationship boundary, but I’m willing to bet I’ll stick out in his mind, even after I’m gone.

Lisa: What are you are most proud of accomplishing?

Jen: Memories with my son, family, and close friends. The walls of my home are covered with pictures from different vacations, photo shoots, and events. I’m not interested in fine art, I’d rather have those pictures, and those memories adorning my walls instead.

Lisa: What do you want to be your legacy above all, besides Corbin, of course?

Jen: I feel like this is a trick question-ha! My legacy…wow, that’s a big one. I think the biggest thing is I would want people to stop being the victim in their own lives. I’ve met so many people who have the attitude that they are the victim, everyone is out to get them.

I guess I would want my legacy to be for those people to take responsibility and control what they can. Don’t get me wrong, bad things happen to good people…and I’ll NEVER say “cancer is a gift.” It is not. It’s a thief and a murderer, not a gift.

But I’ve used having cancer as an opportunity to do some things in my life that I may never have done (leave my job, take a huge cut in pay, but go with the mindset of being on retirement and do things retired people do, i.e., travel!)

Lisa: I know you are a believer (as I am) in writing your own obituary so that certain words or phrases commonly used in describing the death of someone from cancer would be omitted. What did you feel it was most important to include and what language did you specifically want to avoid?

Jen: Language to avoid: “lost her battle” “was an inspiration and fought” “cancer was a gift”

Mostly though, I wrote my obituary and planned most of my funeral because I saw it as a gift I could give my family. At the time of my passing, when they are numb and filled with grief, I didn’t want them to have to try and remember what awards I’d won, what year I graduated high school, or when I started at a certain job. I saw this as a gift that I could provide them.

Lisa: What song do you feel best describes your life or your outlook?

Jen: I’m stuck on this one…not sure that one describes my life or outlook. There are ones that I want played at my funeral for specific reasons/to bring comfort during that time.

Lisa: You and I have many similar approaches to dealing with our cancers. We were diagnosed originally at a similar time and when we each had a child under one year old (I also had a 3 year old and 7 year old at the time). One thing we differ greatly in, however, is religion. You write in your book that you think God has a plan for you and that you believe in Heaven and seeing others after you die. You write that you “could not have gotten through this” without your faith. As an atheist who believes this life is all there is and never prays for nor believes in miracles, I am wondering if/how your religious beliefs have changed as you have come closer to death.

Jen: I’ve witnessed a miracle and I see him every day. I’ve been more forthcoming in sharing the excruciating infertility experience I went through to get pregnant. There is no way the last cycle should have worked. There were too many variables that were not in our favor. But, a miracle happened, and Corbin is living proof of it.

I was raised Methodist and still attend the same church I attended as a child. While I go to church regularly, I don’t consider myself “religious” because I can’t quote Bible verses/stories. I consider myself as having a “strong faith.” I’ve witnessed too many completely amazing things to believe they were mere coincidences. I’ve met people (on mission trips) who are so financially poor that they live in trailer and use an outhouse, yet they are so rich in life.

I see Heaven as a huge “welcome home” party. I remember reading a quote that says: One day God says, “Enough, come home.” And that felt so comforting. I know that I’ll be reunited with family members, friends who were stolen from this disease, and most importantly, the child I carried but never met on Earth. And, I think that in terms of eternity my family/friends/son will join me in the blink of an eye. My faith, which Corbin has learned has brought great relief during this time. He knows that he will see me again and that I’ll be waiting for him at his “welcome home party.”

Lisa: Are there any decisions about your treatment in the past six years that you regret? That you think were not fully explained? I, for example, had an oophorectomy (as you did, too) but feel the side effects and long term health risks of having that surgery (increased risk of lung cancer, for example) were not fully explained. And, on the flip side are there any treatments you feel were particularly important in extending your life?

Jen: I can’t think of any.

Lisa: What are a few things you think are the most important myths we should debunk right here, right now, about metastatic disease?

Jen: I know society and the media have conditioned us to use the language “battle” against cancer, or in the “fight/war” against cancer. This is something that I’ve never really felt connected to. After all, what am I battling? A rogue cell in my own body, so in essence, I’m fighting myself. The best quote I’ve found that relates to how I feel is when Elizabeth Edwards died in 2010. Her friend said, “Elizabeth did not want people to say she lost her battle with cancer. The battle was about living a good life and that she won.”

The other frustrating thing I run in to is “So-and-so tried XYZ therapy and was stable for 10 years, why haven’t you done that one?” Then I explain that I tried XYZ and had progression in 3 months. I think getting people to truly understand that this is such an individualized disease is key. Just because XYZ works for one person doesn’t mean all people will respond the same way.

And, this is just me, personally, but I hate being referred to as “sick.” I’m not sick; I have a disease called metastatic breast cancer. If I was “sick” that would imply that I’m possibly contagious or that I’ll get better, neither of which are true.

Lisa: Your son has never known a time in his life when you didn’t have cancer. He is very astute and caring and sensitive. He is a joyful boy is not afraid of many of the topics and subjects that many parents try to “shield” their children from.

I know you and I both believe that protecting children by withholding information is not the right thing to do. Age-appropriate information dispensed in small pieces is better. Do you notice that other parents are uncomfortable around you and Corbin for this reason?

Jen: Maybe I’m completely naïve, but I haven’t noticed that other parents are uncomfortable around Corbin and me. More often than not, I’m told, “Thank you for being so open. My aunt/grandma/relative had cancer but we really didn’t know about it until she passed.”

I’ve worked to connect with as many as possible and be as transparent with information as possible. People assume that a bilateral mastectomy means a “great boob job” at the end. I’ve posted pictures of my bilateral mastectomy (without reconstruction) to educate others. I’ve also posted a picture of my scan, so when I say “it’s everywhere” they can see the scan that shows it truly is everywhere. This was an especially powerful message because I look so “healthy” on the outside.

Lisa: I’d like to leave readers with your video which is one of the most beautiful tributes to a loving relationship I’ve seen. I implore readers to spend two minutes of your life seeing Jen and Corbin. They will make you cry and make you smile. If there is anyone who knows how to live legendary, it’s Jen.

Jen, thank you for sharing your precious time with me, and with so many others. I promise you that your enthusiasm for life and your powerful message will live on in the hearts and minds of so many. It is an honor to call you a friend.

June 26th, 2013 §

I’ve again invited my mother, Dr. Rita Bonchek, to write a piece for the blog. Her previous posts on the difference between guilt and regret, grieving the death of a parent, what it’s like to read my blogposts about cancer, and how to help children understand death have been well-received. As a psychologist specializing in grief and loss I think her perspective and ability to share insights are welcome additions to the posts I make. I know that she gains comfort from talking with other parents who have children with cancer and sharing their feelings about the way that cancer has affected their roles as parents (and often as grandparents). Her post appears below.

I’ve again invited my mother, Dr. Rita Bonchek, to write a piece for the blog. Her previous posts on the difference between guilt and regret, grieving the death of a parent, what it’s like to read my blogposts about cancer, and how to help children understand death have been well-received. As a psychologist specializing in grief and loss I think her perspective and ability to share insights are welcome additions to the posts I make. I know that she gains comfort from talking with other parents who have children with cancer and sharing their feelings about the way that cancer has affected their roles as parents (and often as grandparents). Her post appears below.

I think the only thing I would say that I might disagree with here is that I don’t think it has to always be a one way street. Mom refers to a time when I was helping her with problems she had in her own life. Yes, perhaps it’s important to be aware of when you are asking your child for help or advice. However, if this is the way your relationship is (ours is, for example), then I believe that maintaining some of this dynamic adds to the sense of “normalcy” that may be elusive but also can be comforting to both parties. That is, if I am not in an immediate medical crisis, helping my mother with a problem she is having feels good to me, rewarding, reminiscent of the way things were before. If the street is always one way, that adds to the feelings of separateness between us, a strong reminder that everything is different.

A suggestion we both have is to focus more on parents taking care of themselves, finding ways to cope in a way that is right for them. Certainly parents and children do not always have the same strategies to deal with medical crises. The parent also may need support to deal with his/her grief during this fragile time. Individuals may find help in talking to a therapist or other supportive figure or attending a support group for parents.

There are constant ebbs and flows in the parent/child relationship based on how treatments are going, anxiety about upcoming tests or bloodwork, and the side effects of treatments. It may not always be clear how much the parent needs to be parent at any given time. Open communication is so important. One of the hardest conversations my mother and I had recently was one in which I openly laid out some ways in which she could be more helpful to me now. That conversation led to a wonderful new phase of support. She feels good that she knows better what I need, how to be helpful to me and to my family. I cannot expect her to be a mind-reader, and the ways that I need support change with how my treatments are going. I will be undergoing treatment for the rest of my life, so it’s important that we are as honest and supportive of each other as possible. I know that she has her own challenges in dealing with my diagnosis. She feels good now knowing some of the things she can do that are most helpful. I truly believe that is what makes a parent feel good is to know they are a help, rather than an additional source of stress for their child during this difficult time.

My mother and I both hope that this piece will be an introduction to this topic. There is so much to say about changing relationships during medical crises. Perhaps today’s post will allow you to raise some of these topics with a family member.

……………………………………

Dr. Rita Bonchek writes:

Throughout this blogpost, I repeatedly refer to children. Even though adult in years, they are our children. When they are diagnosed with cancer, the relationship between parent and child will, by necessity, change. I would like to suggest how parents can strengthen the relationship and cope more effectively at this time.

When Lisa completed cancer treatment after her initial diagnosis (double mastectomy and chemotherapy in 2007, oophorectomy in 2008), everyone, including her doctors, believed that there was an infinitesimal chance that the cancer would return: that period of time was in the past and life would move forward. When the cancer returned in the form of an incurable metastasis in 2012, we were all devastated.

Families have one type of relationship when all of its members are healthy and a different type when one member is ill. But cancer isn’t necessarily just being ill for a period of time, recovering and continuing on with life. Cancer can be a life and death everyday concern. So, what happens? The conversations change because references to cancer are screened , levity is uncomfortable because how can one laugh about trivial jokes when something so serious is occurring and discussions that involve long-range planning are avoided since how long will long-range be.

Who we were as parent and child before the diagnosis of cancer is not who we are and become after the devastating news. The prior carefree mutual relationship now shifts from both of the parties interacting and sharing problems and concerns to only focusing all attention and sensitivity towards the child. There is now a one-way street. How could this not be? When one asks the question “Whose needs are being met?” it must only be the one who lives with the cancer. The goal is, as much as possible, to reduce stress and tension between mother and child but, most importantly, within the child.

There are some tensions that occur when a parent offers to help a child with household chores, fixing meals, carrying packages, etc. A child’s snappish response of “I can do it myself” may indicate that to accept the offer is to admit a weakened condition. Or, any offer to help may cause reminders that at some time sooner or later that help will be needed. It may be better just to do the chore without asking as in folding laundry, unloading the dishwasher, making a meal that could be frozen if the gesture is not accepted. It is MOST important that we do not take personally such behaviors as negativity or curtness. There can be mis-directed anger at a parent instead of directed, expressed anger at the overwhelming madness-sadness of the cancer diagnosis.

It can be helpful to establish ground rules. The parent can ask “What CAN I do for you that would be helpful?” “What should I NOT do that might be upsetting to you?” Those of you who read this blog-post will surely have suggestions that all of us, who are trying to function each day as best as possible for ourselves and for our children, can benefit from reading.

From the day of the diagnosis, our worlds have changed irrevocably for the worse and we must adjust. I may sound as if I knew exactly what to do and employed suggestions proffered. Not so. Just ask Lisa. I let her down. I had personal problems during the time after her diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer and I vented and asked for her advice as she was trying so hard to just get by.

I felt only Lisa knew the participants well enough to understand my dilemmas and to help me. Time after time, I apologized, I vowed that I would not involve her again and she forgave me. But once was not enough, even twice was not enough, for me to learn my lesson and to seek help elsewhere. If I had remembered to ask myself “Whose needs were being met?,” I hope I wouldn’t have placed Lisa in that position. Our children may no longer be as available to support us.

When I was in practice as a psychologist who specialized in grief and loss counseling, I tried to help my patients to understand, process and deal with major losses. I often explained to them that denial was an effective coping mechanism if it allowed them to absorb the overwhelming loss little by little, bit by bit. But denial cannot be total and the reality of the situation must at some time be acknowledged. So, although I do recognize the possibilities of breakthroughs in medical science, I do not believe in nor count on miracles.

I will let my thoughts go a certain distance into the future when I must, but I function day by day as a way of living . I choose not to focus on what may occur in the future because it may not occur. What a waste of time and energy that would be. I cannot focus on the possible downturns during the treatment, on any pain or suffering Lisa could be experiencing but is not telling me about.

The reality is that though I can support and comfort her, there is nothing I can do to make her physical and emotional suffering go away. If I indulged in this negativity and worry about Lisa in my everyday life, I would have no life. I try to remember- not always successfully- that worrying benefits no one. If my worrying could provide even a tiny extension of Lisa’s life, I would worry myself sick.

A line in Joyce’s “ Ulysses” states this emphasis on the present: “Hold to the now, the here, through which all future plunges to the past.”

To derive satisfaction from life, Lisa and I agreed that auditing classes at Franklin & Marshall College would distract me with an activity that would challenge me and bring me satisfaction. And so it has. The last thing we want our children to do is to worry about us. Whatever we do for ourselves, we do for them. Find some interest or activity that gets you through each day.

Lisa and I have quite different personalities and behaviors. As her readers know, she is very open in describing her thoughts and feelings. In contrast, I was a very private person. When Lisa first started writing, I was uncomfortable seeing private information about our family being disclosed publicly and shared with people I did and did not know. But, very soon, I began to appreciate the role that Lisa’s writing played and continues to play in her life and the lives of her readers. And so I changed and re-evaluated my stance on privacy. In answer to the question “whose needs were being met?” I substituted my privacy desire for Lisa’s openness. I stand with Lisa to help cancer patients and their loved ones live with cancer and not die from cancer.

Our daughter, Lisa, is an incredible daughter, wife, mother and friend. I cannot and will not imagine living my life without her.

June 10th, 2013 §

I have my list of things I worry about.

I have my list of things I worry about.

First on my mind in the morning,

Last in my head at night.

And if I pop awake In the middle of the night?

Yes, the list is there too.

Across the aisle from me on the train to New York City last time sat a woman.

At one point on the journey she flipped huge black bug-eye sunglasses from the top of her head down over her eyes, her look now an insect dressed in designer clothes.

She reached in her purse,

grabbed a strand of worry beads and started kneading them.

With a rapid-fire reflexiveness she started moving one bead at a time .

Each only moved about half an inch down the string.

From the worry side to the safe side.

I could hear the rhythmic mantra of the beads again and again and again,

Quieter but still audible over the clickity clack pattern of the train itself.

I wondered what her worries were.

I wondered if she would add mine to hers.

Or trade with me, even.

Sometimes we need to do something with that energy.

For her it was tiny movements, thumb and forefinger

Pinching and sliding ivory beads on a round string.

We have our rituals when things get bleak. Some pray.

I do not.

There is a coping that comes with grief, a way to release the tension that grips us when things are bad.

Some days it does feel like it eats from the inside out.

When you must come to terms with what you fear

and what you dread

and all you want to do is lay down on the floor like a petulant two year old

and kick and scream about the unfairness of it all…

As if the universe gives a damn that life hasn’t been fair to you.

Clearly it doesn’t.

So I do not appeal to the universe to change what is.

I turn to my balms. I turn to research.

I turn to science.

I turn to determination and hope which are the last things I can cling to,

fingertip by fingertip,

like the cat on that iconic poster that says “Hang on, baby.”

Inner strength is sheer will.

My claws are firmly entrenched.

There is no other way to be.

There is no justice.

It’s up to me to come to terms with the weighted side.

That is where I live right now.

And so every day, when I wake up in the pre-dawn hours and contemplate my worry list and

come to terms with the day that is about to dawn,

I gather strength,