October 6th, 2014 §

One of the most common questions I get asked by email is, “Someone I know has been diagnosed with cancer. What can I do?” Today I offer one suggestion. I believe this would make a practical gift for someone who has just been diagnosed and it is a necessity if you are the patient or a caregiver.

One of the most common questions I get asked by email is, “Someone I know has been diagnosed with cancer. What can I do?” Today I offer one suggestion. I believe this would make a practical gift for someone who has just been diagnosed and it is a necessity if you are the patient or a caregiver.

Being organized is one of the best ways to help yourself once you’ve been diagnosed. When you first hear the words, “You have cancer” your head starts to swim. Everything gets foggy, you have to keep convincing yourself it’s true.

But almost immediately decisions need to be made — decisions about doctors, treatments, and surgeries. Often these choices must be made under time constraints. You may be seeing many different doctors for consultations. Medical oncologists, surgical oncologists, radiation oncologists, recontructive surgeons, internists— there are many different voices that you may hear, and they may be conflicting. It’s hard to keep it all straight in the midst of the emotional news. Not only are you likely to be scared, but also you are suddenly thrust into a world with a whole new vocabulary. By the time you are done with it, you will feel you have mastered a second language.

You can help your care and treatment by being organized. You can also have the psychological bonus of feeling that one part of your care is within your control. Especially if you are juggling different specialists and different medical facilities, you must remember that the common factor in all of this is you. It’s your health. It’s your life. I believe it’s important to travel with a binder of information about your medical history and treatment, as well as notes and questions.

This binder will mean that all of your information about your cancer will be in one place. This will be your resource guide. I cannot tell you how many times physicians have asked about my binder and when I was able to instantly produce test results, pathology reports, or other information they needed, they said, “I wish every patient had one of those.”

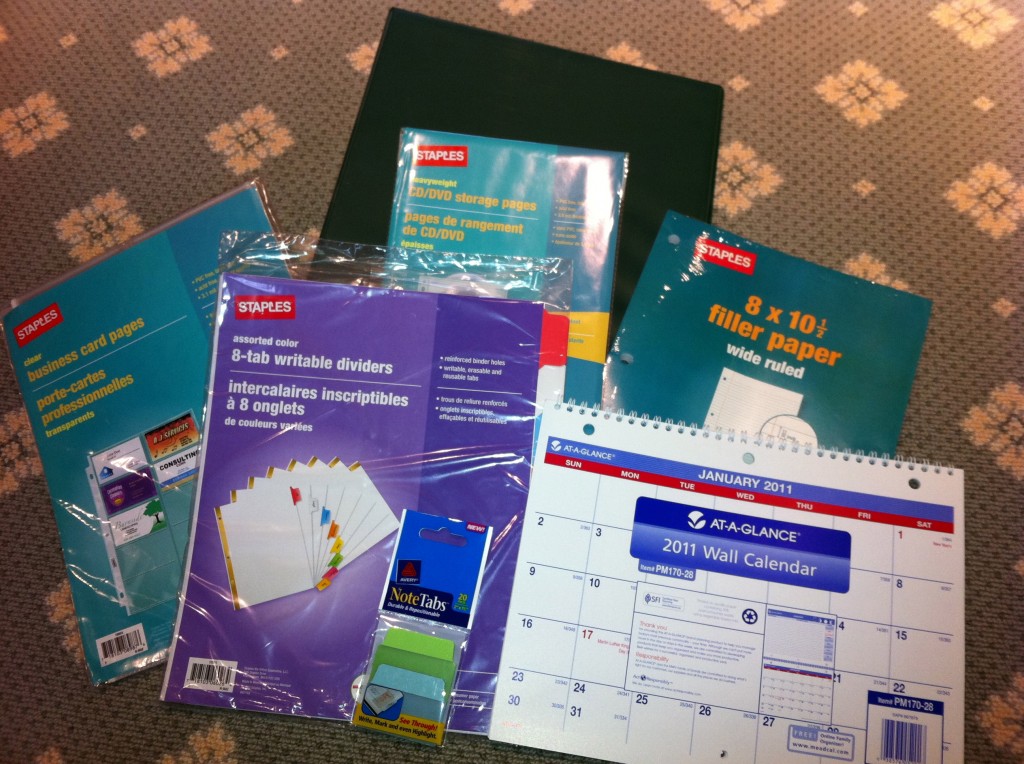

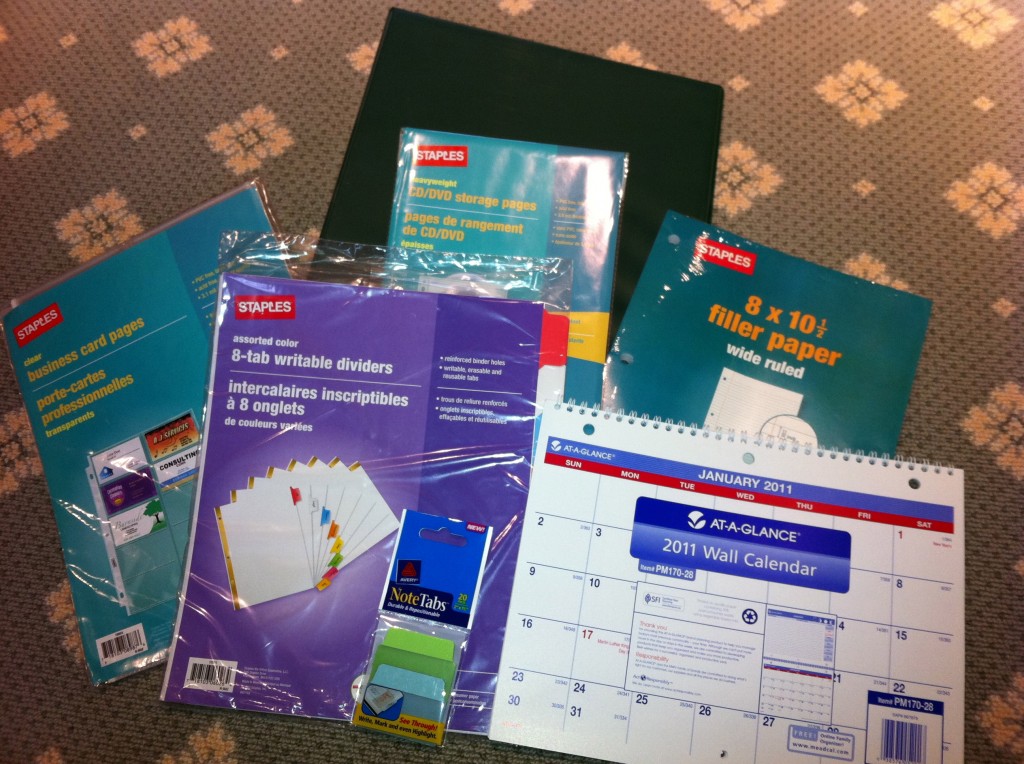

I suggest the following:

A heavy 3-ring binder

I think a 1.5″ binder is a good size to start. This size will allow you to easily access reports and pages and have room for the calendar. It will look big at first but you won’t believe how quickly you will fill it up.

Colored tab dividers

I like these to be erasable. I think 8 is the minimum number you will need. If you have a lot of specialists you will need more. The categories you think you will need at the outset may change. It’s easy to erase and reorganize them. Put the categories you will be accessing the most in the front so you aren’t always having to flip to the back. Once the binder is full it will make a difference.

Some starting categories:

- schedules (dates of appointments you have had, when the next ones are due, and how often you need certain tests done)

- test results/pathology (it’s very important to keep copies of MRI, CT, and pathology reports so that you correctly tell other doctors what your diagnosis is. For example, new patients often confuse “grade” with “stage” of cancer)

- insurance (keep copies of all correspondence, denial of claims, appeal letters, explanations of benefits)

- articles and research (handouts, post-surgical information. Ask if there are any websites your doctor does approve of. My own oncologist said, “Do not read anything about cancer on the internet unless it comes from a source I’ve told you is okay. There’s a lot of misinformation out there.”) Keep your post-surgical instructions, any info given to you about aftercare.

- radiation/chemo (keep records of exactly what you had done, number of sessions, dates, drug names, etc. I also asked how my dose was calculated so I knew exactly how much of each drug I received in total)

- medications (drug names, dates you took them, dosage, side effects). I also keep a list of all of my current medications as a “note” in my iPhone. That way I can just copy it down and won’t forget anything on the list. You should always include any vitamins or supplements you take.

- medical history (write out your own medical history and keep it handy so that when you fill out forms asking for the information you won’t forget anything. As part of it, include any relatives that had cancer. Write out what type it was, how old they were at death, and their cause of death. Also in this section include genetic test results, if relevant)

Loose leaf paper

Perfect for note-taking at appointments, jotting down questions you have for each doctor. You can file them in the appropriate category so when you arrive at a doctor your questions are all in one place.

Business card pages

These are one of my best ideas. At every doctor’s office, ask for a business card.Keep a card from every doctor you visit even if you ultimately decide not to return to them. If you have had any consultation or bloodwork there, you should have a card. That way, you will always have contact information when filling out forms at each doctor’s office. For hospitals, get cards from the radiology department and medical records department so if you need to contact them you will have it. Also, you want contact information for all pathology departments that have seen slides from any biopsy you have had. You may need to contact them to have your slides sent out for a second opinion.

This is also a good place to keep your appointment reminder cards.

CD holders

At CT, MRI or other imaging tests, ask them to burn a CD for your records. Hospitals are used to making copies for patients these days and often don’t charge for it. Keep one copy for yourself of each test that you do not give away. If you need a copy to bring to a physician, get an extra made, don’t give yours up. If you need to get it from medical records from the hospital, do that. You want to know you always have a copy of these images.

Keep a copy of most recent bloodwork (especially during chemo), operative notes from your surgeries (you usually have to ask for these), pathology reports, and radiology reports of interpretations of any test (MRI, CT, mammogram, etc.) you may have had. Pathology reports are vital.

Calendar

I suggest a 3-hole calendar to keep in your binder. This will serve not only to keep all of your appointments in one place but also allow you to put reminders of when you need to have follow-up visits. Sometimes doctor’s offices do not have their schedules set 3, 6, or 12 months in advance. You can put a reminder notice to yourself in the appropriate month to call ahead to check/schedule the appointment. Some people like me prefer to use their phones for this, including reminders.

Similarly you can document when you had certain tests (mammograms, bone density, bloodwork) so you will have the date available. I usually keep a piece of lined paper in the “scheduling” section of my binder that lists by month and year every test/appointment that is due and also every test I’ve had and when I had it.

Sticky note tabs

These can be used to easily identify important papers that you will refer to often, including diagnosis and pathology. These stick on the side of the page and can be removed easily. As your binder fills up, they can be very helpful to identify your most recent bloodwork, for example.

Plastic folder sleeves and sheet protectors

These are clear plastic sleeves that you access from the top. They can be useful for storing prescriptions or small notes that your doctor may give you. The sleeves make them easy to see/find and you won’t lose the small slips of paper. Also a good place to store any lab orders that might be given to you ahead of time.

The above suggestions are a good working start to being organized during your cancer treatment. If you want to do something for a friend who is newly diagnosed, go out and buy the supplies, organize the binder and give it to your friend. He or she will most likely appreciate being given a ready-made tool to use in the difficult days ahead.

I also believe a modified version is equally useful for diagnoses other than cancer. When our youngest son was born with defects in his spine and hands it took many specialists and lots of tests to get a correct diagnosis. Having all of his tests and papers in a binder like this was instrumental in keeping his care coordinated. In fact, at his first surgery at The Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania they gave us a binder to assist in this process. I know some hospitals do this for newly diagnosed patients already.

Maybe my tips will help you or a friend know how to better use the one you already have. You may not need all of these elements depending on the complexity of your case, but I hope you will find some of these suggestions useful.

March 7th, 2013 §

Everything changes with a diagnosis of Stage 4 cancer. I don’t really think that’s an overstatement. My relationship with my oncologists has, by nature, changed as well. With stage 4 one of the things that’s especially important is good communication between physician and patient. It always is, but now two of the topics that are imperative to review at each meeting are side effects of medications/chemo and symptoms I’m having (especially pain).

Everything changes with a diagnosis of Stage 4 cancer. I don’t really think that’s an overstatement. My relationship with my oncologists has, by nature, changed as well. With stage 4 one of the things that’s especially important is good communication between physician and patient. It always is, but now two of the topics that are imperative to review at each meeting are side effects of medications/chemo and symptoms I’m having (especially pain).

I have always had two oncologists’ input on my treatment since my original diagnosis of stage II breast cancer in December of 2006. Even through the more than five years of remission, I continued meeting with them about my adjuvant therapy.

Immediately after I was diagnosed in October with stage IV my oncologists began talking about finding a balance between length of life and quality of life. These two aspects of my life would have to be constantly juggled. The art of medicine and its role in treating cancer suddenly has become crystal clear while the science of decision-making often remains blurred.

For many people it is often reassuring to hear there is a plan, a prescribed protocol. There is a type of comfort in being diagnosed with a disease and being told there are defined steps you need to take. With metastatic cancer it’s not crystal clear. Patients must often help decide what is right for them.

I was offered options about which treatment to try first: a traditional chemo or an anti-hormonal combination. One would attack cancer cells, but also attack the healthy cells in my body. The other would aim to “starve” the cancer of some of its fuel (hormones). One important positive feature about my cancer is that there are choices about how to try to keep it in check. This hopefully will equate to having stable disease for a while so I can live longer. Some types of cancer do not respond to certain therapies and therefore there are fewer options in treating them.

When I went to see my medical oncologist at Sloan Kettering, this week she pulled the chair over and sat only inches from me. I was on the exam table, in the modest red and peach Seersucker bathrobe Sloan uses for their exam gowns. We sat and talked about research and trials and side effects and my blog and my family. She gets emotional sometimes when we talk about the current situation. So do I.

Then Dr. Chau Dang said something that I will always remember. She said that many doctors start to distance themselves from their patients as the patients get sicker and closer to death. She said this is their coping mechanism. Of course I couldn’t help but wonder if the same process is what is behind some of my friends disappearing and rarely contacting me anymore. Some physicians, she said, seem to back away, needing emotional distance not to be weakened each and every time a patient dies.

In contrast, my doctor feels this is precisely the time in her relationship with her patients to embrace them, bring them close, provide them care and comfort as much as possible. It’s important to remember, she always says, that this isn’t a case, this is a life. A person with friends and families who love them. Death happens for all of us. It’s her role to do what she can to prolong life, and when that can’t be done anymore, it’s important to still care for the person, not just treat the disease.

The nature of the doctor-patient relationship changes over the course of illness. Perhaps nowhere is that truer than in oncology. I’ve always been a partner in my care, it’s the only way I know how to be. It’s my life, after all, and the decisions we make as a team are ones I do not want to regret because I gave up control or didn’t have adequate information. However, I also accept that treating cancer is not an exact science.

Some patients do not want to have options. They want their physician to pick the course of treatment that seems best matched for the patient and proceed. A patient sometimes doesn’t want choices; he or she wants the doctor to do the sifting and prescribing. This works for many people, and takes the responsibility off the patient. There is mental comfort in that approach, too. I can understand why some people make that choice.

One of the things that is difficult in being a true participant in your own care is that while you get the satisfaction of partial control, you also must accept responsibility if/when things go wrong. This is part of the deal.

Some things just are.

Some things just happen, even when you do all you can.

I have accepted this jagged truth all along.

But I think some people never do.

December 30th, 2012 §

It’s true:

you’d never know.

I look great. I look healthy. I’m not gaunt or drawn or pale.

I wear makeup most days, and some days I ever wear boots with a heel on them.

I smile, I laugh.

I take a slight jog up the front hall steps when I feel like it.

I crack jokes, I roll my eyes when standing in a long line, I gossip with my friends.

I wear gloves a lot, I have to moisturize my feet and hands at least a dozen times a day.

I buff my feet, I examine them for cracks and bleeding. I stick ice packs on them when they burn from the chemo.

I can’t feel my fingertips, yet portions of them crack and peel and are painful and raw.

I can’t hold a pen or twist off a bottle cap.

I take pills all day long.

I’m swollen, I’m tired, my mind can’t stop racing.

I tell time by “on” weeks and “off” ones.

Of course the doctors understand my situation.

They know what this diagnosis means.

Even ones that have nothing to do with cancer call to check on me.

When I go to my sons’ school some of the teachers and moms cry when they see me.

“You look good,” they say. This a compliment. Sometimes they say, “You don’t look sick at all. You’d never know.”

That is shorthand for, “You don’t look like you’re dying but we know you are.”

I hear people in line to buy holiday gifts complain about the sniffly cold they have or the poor night’s sleep their child had.

They might be complaining about something more serious, but still something that can be fixed.

Time will heal what ails them.

I am not so lucky.

I am jealous.

I am jealous that this is their only medical concern.

I’m not jealous of what they wear or the car they drive or the house they live in.

I’m jealous of their health status.

I’m not in denial. This diagnosis is a nightmare.

My life will always be full of chemo and side effects and worry and monitoring and drug refills and hospital visits.

But my life will also be full of great memories, of laughter, of smiles.

There will be tears. There will be pain. There will be heartache.

But there will also be joy, and grace, and friendship.

I don’t know for how long. I don’t know if they will be in equal measure.

They say I look good. They say, “You’d never know.”

For now I know it’s true.

There will come a day when it’s not true.

And they will lie.

And I will know it.

And someday, then, I will know the end is near.

But that day is not today.

December 20th, 2012 §

Today marks the six year anniversary of the day I was first told I had breast cancer. When the radiologist told me the news, she also said she didn’t know exactly what it was or how bad it was.

This is why you do not schedule mammograms or biopsies right before a holiday. Especially Christmas. You’ll be going on vacation… and if you aren’t going on vacation, the doctors, nurses, and pathologists will.

I was told on December 20, 2006 that I almost certainly had cancer based on the mammogram and ultrasound images. I’d need a biopsy to confirm it. But they couldn’t do the biopsy until after the new year. It’s hard to hear, “We think you have cancer. Now go on your vacation and when you come back we’ll figure it all out.” Weeks later I was told I had extensive DCIS and would need to have my left breast removed. I opted to have a double mastectomy. A few weeks later a second look at the slides revealed I had some breast cancer in one of the lymph nodes that had been removed (I am now a big advocate for a second opinion on pathology). I was reclassified as having stage II breast cancer. I had chemotherapy; later, a salpingo-oophorectomy.

Almost six years later, I have now found out that I have stage IV (metastatic) breast cancer (details here).

Yesterday I went to an appointment with my local oncologist. I go to see him every two weeks right now to review bloodwork and to discuss dosing for the next round of chemotherapy which starts tonight.

The concept of “good news” has been completely redefined since my new diagnosis. There is no cure, so I can’t hope for that. There is never going to be a day I am not aware of running out of time. Now “good news” gets defined as stable disease. If you’re lucky, and the chemo is working, good news can even mean reduced disease. Now I hope for that.

I look at my oncologist’s face when he walks in the room. I scan it for signs of what kind of news day this will be. The day he told me about my metastasis I read his face. When he walked in that day I asked him how he was and he said, “Not good.” I assumed it was something about him, his family. I immediately starting worrying about the bad news he was going to tell me about someone else. But it was my bad news. It was my nightmare.

I never used the word cured. I never said it. And I don’t like when others do with my kind of cancer. I always prefer the technical terms NED (no evidence of disease) which means it may be there, but we can’t detect it with the tests we have done. I don’t even like the term “cancer-free” for my particular cancer… again, there might be cancer there, but just not enough to be detected or can’t be with the tools used.

Five years had come and came and gone. Even nurses in other specialties would say at my checkups, “Oh! Five years! That means you’re cured!” and when I’d explain to them that it actually didn’t mean that at all with my kind of breast cancer they would look at me quizzically.

“SEE?! I told you!” I want to go back to say to all of them. I was vigilant for a reason. It “shouldn’t” have happened based on the statistics, the predictions. But it did. And now the only life I’ve got is spent dealing with it.

……………..

I watched my oncologist’s face yesterday. We’ve had some bloodwork results in the last two months that have been a good first step but he hasn’t been willing to budge much on declaring that this chemo is working. One or two data points are not enough for either of us to feel confident, actually. But yesterday we got our fifth data point.

I still have metastatic cancer. That isn’t going to change.

But I have some news I can finally share: my bloodwork is showing “indisputably” (in the words of my doctor) that my cancer is shrinking. The chemo is working. The pills I’ve been swallowing, seven or eight a day for seven straight days at a time, in alternate weeks, are doing what we’d hoped. The cancer is still there. But it’s smaller. But it’s responding. It’s been consistently trending down since I started on Xeloda. Now, with more than a few data points, we can finally characterize the effect and I can share it publicly.

……………………….

So what does that mean? I know that’s the question most will ask. It simply means this is the chemo I stay on for now. It means that I just keep doing what I am doing. I’m not “cured” or “feeling better” or “cancer-free.”

It means that modern science and pharmaceuticals are giving me some time. For today, the cancer is responding, shrinking. And in the land of stage IV cancer, that’s unmitigated good news. Make no mistake, it’s no Christmas miracle. It’s not happening for any other reason than the fact that I am aggressively taking as strong a dose of this drug as I can tolerate, and it’s doing its thing.

Six years ago I went on Christmas vacation and feared for my life. I was scared and confused and miserable. Now, six years later I’m in a much worse place vis-a-vis cancer but my mindset is different.

I’m coming to terms with accepting the life I have — the one I thought I’d have is gone. I have created a new one. The best one I can.

For today, I celebrate the good news. I will go to my children’s school holiday parties. I will smile. I will make memories. I will not focus on side effects. I will find beauty in something small.

I will savor the things I can do today.

December 8th, 2012 §

I realized it’s time for an update… but confess I’ve started and stopped this one a few times. Somehow when things are going along somewhat easily it’s easy to do the updates.This is the first one I’ve had to discuss side effects and I hesitated a lot about what to write and whether to post it. I wasn’t sure about talking about these things lest they be seen as complaining. My goal has always been to educate and inform above all.

Friends on Twitter assured me that talking about the daily in and out of chemo treatment for metastatic cancer is important. Not only are they learning what it’s like, but it tells people what I’m dealing with and what activities might be hard for me on a daily basis. One Twitter follower also said that for those who have family members with this disease and might not be forthcoming with detailed information, some of these updates give them an idea of what it might be like for their loved ones. While treatments and surgeries vary so much, I thought this was an excellent point.

I also have decided to post this information because I know other metastatic patients will find it through search engines and maybe it will help them. So… I’ve opted to continue to share these things. It’s the reality of cancer. It’s the reality of MY cancer.

I’m struggling at the moment with Palmar/Plantar Erythrodysesthesia or Hand/Foot Syndrome (HFS). This is a common side effect of Xeloda, the chemo I am currently taking. In short, the capillaries in the hands and feet rupture and the chemotherapy spills into the extremities. Redness, swelling, burning, peeling, tenderness, numbness and tingling can accompany it. While it does not always start right away, once you’ve had a few rounds it’s likely to be a cumulative effect.

After receiving another monthly IV infusion of Zometa to strengthen my bones on Tuesday, I started a new round (#5 for those of you keeping track at home) on Thursday night, and had to decrease my dose slightly to deal with the HFS. Rather than 8 pills a day (4000 mg) I’m on 7 now. The hope is that the HFS will stay at its current level and not progress on this dose. This is what feet start to look like with HFS:

It can get much worse than this with blisters and ulcerations but mine is not at that stage. If it were to reach that point we’d have to stop chemo until it healed and then re-introduce it. Driving was one of the hardest things yesterday, the pressure from the steering wheel (or anything against my hands) was difficult to tolerate. I wear cushiony gloves most of the day now and follow all of the guidelines to keep it at a minimum. My hands are more sore and sensitive than my feet this week but not as red as my feet. Thankfully while I could not hold a pen during most of the day, I could still do some typing. A long-term side effect of this particular drug is the potential to lose your fingerprints. I see an episode of CSI coming on that one! An article about the difficulty traveling with such a condition appears here.

Loss of appetite continues to be an issue but my weight has stabilized after a 20 pound loss in the first 6 weeks. It’s weight I needed to take off anyway, actually. I must eat twice a day when I take chemo and once I start eating I usually do just fine. I do better eating in the evening. My blood counts remained fine even during the weight loss and my instructions have been to “keep doing what I’m doing.” The one thing I can’t do is exercise at the moment. Friction on my feet can exacerbate the HFS so for now it’s not happening. A soon as the rib in my shoulder heals I will be trying to get back to Pilates class.

I’ll be back at Sloan Kettering on Tuesday, 12/11 to meet with my oncologist. We’ll evaluate the HFS by then and talk about ways to help me deal with it and make me more comfortable. We will also then be talking about what dose I will take for my next round and also start talking about when my next PET scan will be.

That’s the update for now, I’m still doing everything I can and am out and about as much as possible. I still bring the kids to the bus in the morning and try to do errands like the grocery shopping as often as I can. I ask for help with things that really are tough on my hands like stuffing the holiday cards or doing laundry or dishes. Even small tasks give me a sense of accomplishment and normalcy so while the weather holds I continue to do them. Once ice and snow set in and my concerns about slips and falls and bone breakage rise I will get help with more of the outdoor things.

I’ll have more pieces coming out on HuffPo shortly; thank you all for the excitement and congratulations about that new venue. My piece about what to do as soon as you are diagnosed, especially in regard to children, will be the next one they post. After that I’m looking at writing on the topics of bravery/inspiration, the situation when people you barely know take your condition as seriously as if they were family members, and the story of how I found out I had metastatic cancer to begin with. If you have any topics you’d like to see a piece about leave a comment or email me via the contact form and I’ll definitely take it into consideration!

Thanks for all of the support this week.

October 5th, 2012 §

I loved the book The Age of Miracles by Karen Thompson Walker. I had the pleasure of meeting the author a few months ago. In the book, the earth’s rotation starts to slow. The days stretch longer with obvious consequences on daily life with some not-so-obvious effects on personal lives. I found the book immensely readable, creative, and thought-provoking (My teen daughter thoroughly enjoyed it too. It’s absolutely appropriate for that age group).

My own life has suddenly taken an opposite turn. It feels as if the world has sped up. The days are flying by. There just isn’t enough time.

It’s only been four days since we had an inkling from my oncologist that I had metastatic breast cancer, three days since I have known for sure. And now, in the middle of the night, it’s time I long for. The Earth is spinning so fast… how can it be I’ve been awake for two hours? Have I spent them wisely? What else could I be doing with those days, minutes, seconds?

I’ve done so much already.

I wanted to share a few ideas on things I’ve done already, many of them pertaining to my children. In the dizzying days after a metastatic cancer diagnosis there is so much emotion that it might be hard to think about what to do. You feel helpless. In some ways you are helpless until you get more information. But in the meantime here are some tips about what you can do.

I understand that not all of my readers have children. But for those of us who do, helping children adjust to this news is vital. It not only helps the children but can help relieve some associated stress for the parent.

- Don’t share your news until you know for sure what your particular diagnosis is. I don’t think you need to know your exact treatment; that takes time. But even knowing a general range of what might be used is helpful. If you have had cancer before, children will usually want to know if you will be doing the same thing (especially if it has to do with hair loss) or if it will be different.

- In my case I needed to have a mediastinoscopy with biopsy after my status was confirmed. It’s an outpatient surgery that inserts a camera through an incision in your neck to grab some lymph nodes for biopsy. I decided to focus on that concrete event mostly… it’s something children can wrap their heads around… Mom is going to the hospital (not uncommon in my household), having a small operation, will be back tomorrow night. I explained the cancer, the metastasis, and answered lots of questions, but I think the “one step at a time” was more easily tangible with the surgery as the immediate hurdle. If you will need an overnight stay for your particular surgery I think it’s best not to spring that news on children if possible. An overnight absence is best with a few days’ notice. Children, in my experience, are usually a bit clingy after bad news and that would provide the opportunity for follow-up questions and reassurance.

- Be sure you understand your diagnosis. Explain what words mean to children and to your friends. There are many misunderstandings about cancer and stage IV cancer. The word “terminal” might be scary. Stage IV cancer is not the same diagnosis in different diseases. Prognoses vary and some types of metastatic cancer can be slow-growing or respond well to treatment, allowing years of life.

- I think the phrase “it’s not curable but it is treatable” is important to teach and use.

- Wait to share your news publicly until after you have told your children (except with a few close friends you can trust to keep the information to themselves. This determination may not be as easy as it sounds). This also gives you a day or two to begin adjusting to the news so that when you do discuss it with your children you might have emotions a little more in check.

- As soon as you tell your children, be sure to tell adults who work with your children on a regular basis. If your children have learned the news, by the time they go to school, lessons, and sports, their teachers need to know. Email coaches, teachers, school administration, guidance counselors, school psychologists, and music teachers. Grief in children is complicated and it’s important that all of the adults know and can be on the lookout for odd behavior. Also, they need to be understanding if things don’t seem to be running as smoothly at home or a child seems tired or preoccupied. Two-way communication is key. Adults need to know they have the opportunity to bring any problems they see to your attention easily. Encourage them to do so, whether what they observe is positive or negative.

- Use counselors, especially school psychologists. My first call yesterday morning before I left for surgery was to reach the high school psychologist. Because Paige is in a new school (high school) I didn’t even know which person it would be. Even though it was only 9 in the morning when I called, the psychologist had already received my email (forwarded from the guidance department to the appropriate person) and had a plan in place to find my daughter during 2nd period study hall. She was able to introduce herself, talk to my daughter, and let her know how to get in touch with her as needed. They set up an appointment to meet to talk more in depth after their initial chat. Paige likes her, feels comfortable with her. This resource is invaluable. After my mother-in-law was killed in a car crash 3 years ago, the middle school guidance counselor became a refuge for Paige. When she was sad, distracted, needed a place to go have a good cry or talk, she had a safe place with an adult to help her. These individuals are part of my team. We are working together and it’s so important to use them.

- I have always felt that it’s important to be honest about a diagnosis; that is, open and public. I know this doesn’t work for everyone. The downsides of being public about a diagnosis are outweighed by the negative pressure for children if they have to keep a secret and bury feelings about such a serious topic. Children take their lead from you. If you are up front and comfortable discussing it, your children will learn to be that way, too.

- Call your other medical professionals and tell them of your diagnosis. Not only will they want to know because they care, but there may be instances where treatments may need to be examined or medications evaluated more often (for example, my endocrinologist wants to monitor my thyroid hormone levels more often than usual). They are all part of your team. They want to know. Many of the most touching and heartfelt phone calls I got were from my doctors this week. They cried with me, gave me information, offers of help, and caring. It also means if you have a situation when you need urgent medical care their office will already be aware of the situation and will likely respond more quickly to get you in to see the doctor.

- A carefully worded email is invaluable. Accurate information is documented so people don’t spread rumors. Friends can refer back to it if needed without asking you. They can forward it to other individuals easily, as can you. Choose your words carefully. The words you use will be repeated so make sure the email says what you want it to say to friends and relatives. The right explanation is much more helpful than a quick one sentence Facebook status update. People will have questions, and you can head many of them off by including that in your email (if you so desire).

I will be posting more tips about what I’m doing in the weeks and months ahead. Hopefully they will help you or someone you care about. There is so much you can’t control during this time, and that’s unnerving. Even taking steps like these can give you concrete tasks and a feeling of accomplishment that you are helping yourself and those you love.

October 3rd, 2012 §

Dear friends and family,

This is the last post I ever wanted to make but you all know that I am open and honest to a fault. Many of you noticed that I have not been online all week. Some of you checked in on me.

Some of you have heard the news by now: this week I received confirmation that my cancer has returned, now it has metastasized to my bones. It is not bone cancer. It is breast cancer that is in my bones. This means it’s stage IV breast cancer.

On Thursday I will have surgery to go in through my neck and retrieve some lymph nodes in my chest for testing. This will establish the hormone receptor status of the disease. My cancer was hormone receptor positive the first time around, we need to see if it still is or whether it’s converted. This is important in that it tells us what drugs to try first to contain the disease.

This is not curable. The goal is to keep it growing slowly and keep it at bay for as long as possible. At this point how long that is is pure speculation, we need to see how it responds to drugs I will take. These could range from oral anti- hormone treatments to daily injections to IV chemo again. There are many different types of things they can try to use on this. I have already had a double mastectomy, chemo, and my ovaries removed to try to keep this from happening. Unfortunately my efforts did not work.

I will be writing more in detail about how I found out the cancer was back (be your own health advocate!) and writing along the way about what’s happening and what treatment is like. I know not all of you are readers of my blog; that will be the best place to get updates for now. My goal has always been to de-mystify this disease and its treatment as much as possible and I will continue to do that to the end. For now I am focused not on the end result but on the potential for science to provide me with treatment that will give me years of happiness with my beautiful husband and children. I do not know how many those will be.

If you want to receive emails of the blogposts (no pressure!) you can go to lisabadams.com and enter your email address in the upper right. Be sure to look for the message in your inbox; you have to confirm that message to receive the updates. You can always just drop in to the website for an update if you don’t want to get them automatically. I will need to use the blog to do updates mostly because the updates will become time-consuming and I hope to do them in a public way to allow other people to read what this part of cancer is like. Those of you who follow me on Twitter, I will continue to be my prolific self as much as possible. My friends there are real friends in every way and have become some of my strongest in-real-life friends and were the first to pick up on the fact that something was wrong.

For now there isn’t anything we need. I’m hibernating and will need a few days to recover at home from the surgery tomorrow. You will see people around in the coming months who are helping me with the house and kids. My mom and dad will come at various times as well.

I ask that you not ask the children too many detailed questions right now. They will be getting used to this way of life again. They know my cancer is back. They know I will be treating it. We are leaving it at that for now to let them adjust to this while we gather the necessary information.

I know I have a great family and support system with all of my friends and I already am seeing the help and love they can give. I thank you for your concern, thoughts and wishes and you know I will be giving this everything I’ve got.

Please understand if I cannot respond to every message in a timely fashion. Your words mean so much to me but there are only so many hours in the day right now during this hectic time. I do read every single one though, and am buoyed by each.

Much love,

Lisa

April 13th, 2012 §

In the past few weeks a flurry of news articles discussed the topic of overtreatment in medicine. From both sides, suddenly, we are hearing physicians (“Doctor Panels Recommend Fewer Tests for Patients”) and patients (“Do Patients Want More Care or Less?”) proposing what seem as a controversial idea: less care may be, and often is, better.

My thoughts on this topic stem from a variety of influences: my father spent his career as a cardiothoracic surgeon and now is editor of the Journal of Lancaster General Hospital. My mother spent her career as a psychologist. I have a graduate degree in sociology. Five years ago I was diagnosed with stage II breast cancer. I have a son with congenital defects in his spine and hands.

I list some of these influences because they are important sociological variables and have surely affected the way that I think about this subject. It is often the case that anecdotal evidence supplants cumulative scientific data when people make decisions; that is, if you or someone you know has had a certain experience, that information will weigh more heavily into your thought process than knowing what “the statistics show.”

When I underwent a double mastectomy and completed chemotherapy for my breast cancer, my two oncologists and I sat down in separate meetings to discuss the always stressful: “What now?” I had hormone-receptor positive cancer (breast cancer that is “fueled” by estrogen and/or progesterone) so I was able to take adjuvant therapy. I opted to have my ovaries removed even though I am BRCA-1 and 2 negative.

But what about screenings? After my double mastectomy they told me I wouldn’t get mammograms anymore. I would, however, do “tumor marker tests” that measure levels of antibodies in the blood. They are not very reliable, and therefore are not good screening devices. This is why they are not yet used for the general public and some oncologists don’t even use them. The tumor marker tests can sometimes show if cancer has returned before other symptoms show. Because the tumor marker tests are done via routine bloodwork, the tradeoff seems acceptable to us. The tests are relatively benign. When it comes to other testing, however, the bigger discussion started with my oncologists.

What about PET scans? Chest x-rays?

Discussions about screenings and testing are negotiations of sorts. As the new research and guidelines indicate, doctors and patients are often at odds on how much monitoring is “just right.” I propose that one of the most important variables in this discussion has been overlooked: the psychological ability of the patient to tolerate ambiguity. That is, I believe there are some people who can live with uncertainty better than others, and the amount of uncertainty a patient can accept in his/her treatment should be an important consideration in current discussions about overtreatment of patients.

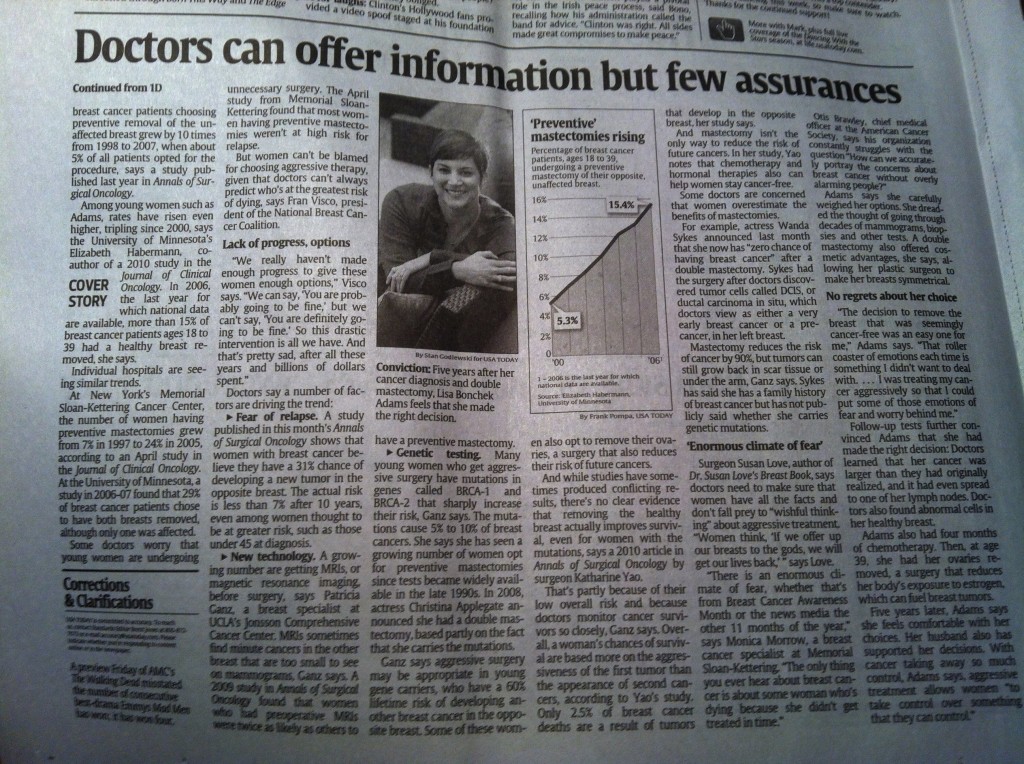

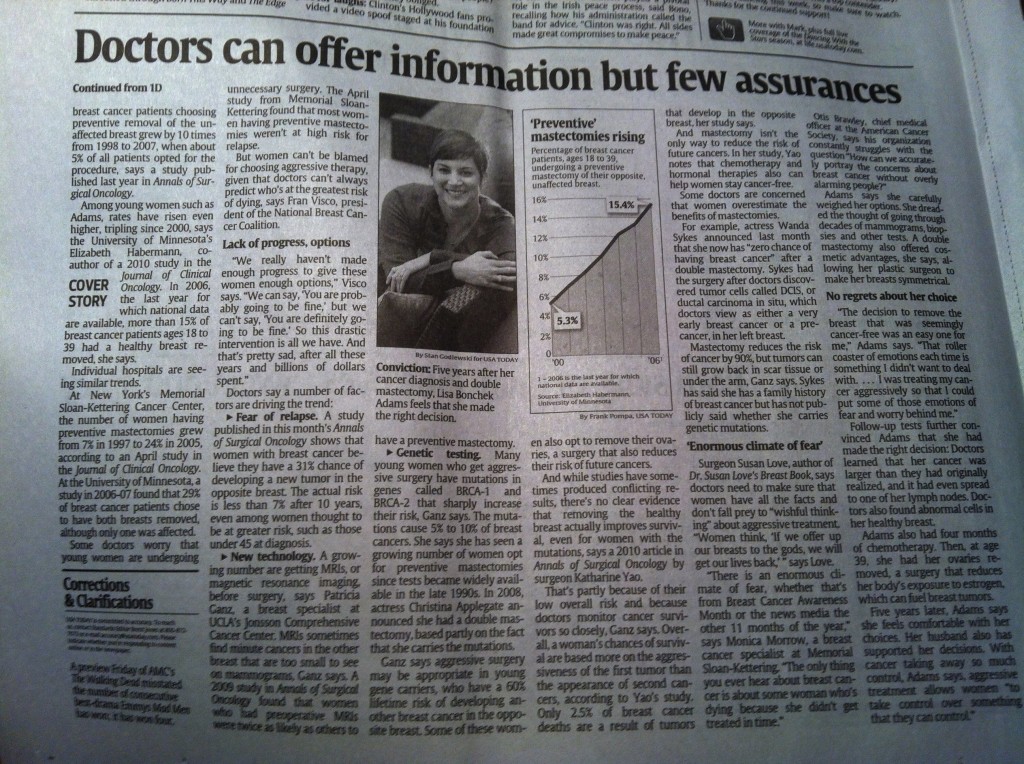

The decision to have a prophylactic mastectomy on my right side, for example, was in part made because I didn’t want to worry about getting a new primary breast cancer on my other side. Some consider this decision controversial and I’ve spoken about my thought process here in USA Today with a followup to critics here.

Screenings are not always benign. While blood tests may be considered simple, they still cost money. Mammograms, x-rays, CT scans, and PET scans all expose the patient to radiation in varying amounts. Many patients are not aware of the relative radiation exposure that screening/diagnostic tests pose. For example, a chest CT provides nearly 200 times the amount of radiation as a two-view x-ray of the chest. A helical abdominal/pelvic CT provides the same amount of radiation as twenty 4-view mammograms (full article here).

My oncologists were quite clear five years ago: there would be no PET scans for me. I worried: after all, shouldn’t I be monitoring my body for any residual cancer? In my particular case, they were adamant: no (of course there are many cases where this risk-to-benefit ratio is different and PET scans are necessary. There are many factors used to make this decision). These decisions are not solely about radiation exposure; they also take into account how likely tests are to yield false positive results on a PET scan. There are many reasons why areas may “light up” in a scan, arousing suspicion. If any areas do light up, this could provide more anxiety and opportunity for additional testing, most often unnecessarily. Not every suspicious area can be biopsied, and you can’t biopsy every time something lights up. Instead, watchful waiting with a keen eye to symptoms of potential recurrence is what we’ve determined is best. I do get a chest x-ray each year. I do tumor marker tests. I follow up with my physicans if there is pain that doesn’t resolve (which can sometimes be a symptom of a cancer recurrence).

I’ve taken a different approach in the past few years with tests not only for myself but also for my children. I always ask “Is this really necessary? Is it important? Does it need to be done this often?” This is not to say that the test won’t happen. I’m not arguing with the providers. But discussing these topics is important. Frequently, tests or screenings are suggested with a time range and now, with with some tests, if screenings have been clear in the past, longer intervals may be used in the future (Pap smears, dental x-rays, etc.). It is worth reading about some of these options and talking to your doctor/dentist about them.

Research shows that antibiotics are not needed (and no more effective than placebo) for many common illnesses like bronchitis, sinus infections, and ear infections. Yet, patients often clamor for them.

As I talked about in the USA Today interview/response piece, there are many factors which come into play when deciding what surgery one wants to have and what level of follow-up care is right for patients. This determination is one that a doctor and patient must come to together. Each must rely on the other to help navigate the murky waters of staying healthy. That said, our healthcare system does not often allow for such conversations to occur and does not reward doctors for the time needed to have in-depth conversations with their patients. Further, physicians are still concerned with liability if they opt to reduce testing on a patient and they miss a problem.

One variable that I think will help doctors and patients come to a more mutually satisfying relationship is a determination of the patient’s tolerance for uncertainty. With this information, physicians can identify more pointedly which levels of acute treatment and long-term follow up care are both psychologically acceptable to the patient and medically reasonable.

October 24th, 2011 §

Last week I was featured in an article by Liz Szabo in USA Today. You can find the story here. It was so much fun to see how many people saw the piece and for the kids to see themselves in a national newspaper.

The decision to have a mastectomy is not an easy one. Many men and women with breast cancer are thankful that their cancer is in a location where the tumor and surrounding tissue can be removed. When faced with cancer the reflexive reaction may be “just get the cancer out.” Statistics on recurrence and mortality rates with certain treatment options are handed over; a new language is learned, risks are assessed. How much risk is acceptable?

Dr. Susan Love, noted breast surgeon, argued in a blogpost recently that decisions by breast cancer patients to have mastectomies constitute “wishful thinking” on their part.

I agree with a few of the points Dr. Love makes, first and foremost that a mastectomy is not equivalent with a “cure” and that it does not ensure cancer will not recur. The problem is that her post really makes it sound like she is arguing with the decision.

In my case, I needed to have one breast removed; I opted to have the other removed as well.

Let me be clear: I had no delusions that a contralateral mastectomy was going to save my life or even prevent me from having a recurrence. I knew I could not control if my cancer would return. What I knew is that I could control how I treated my cancer, how I managed it, how I lived with it/after it. I knew there would be choices to be made. I knew cancer would not be a “once and done” thing for me. Survivorship means living with the ramifications of the disease, long after hair has grown back in.

I also very much agree with Dr. Love’s critique of food and eating particular items to prevent breast cancer or keep it from recurring. Dr. Love writes:

Finally, there is the wishful thinking about diet! The headlines scream that if you eat blueberries or drink red wine or don’t drink red wine you will not get breast cancer. We all want to believe this magic!

In reality, these findings come from observational studies, which show you a correlation, but cannot prove cause and effect. If you knew that all drug addicts drank milk as babies, would you really think that drinking milk as a baby could make you a drug addict? Of course not! That’s a correlation. It’s not cause and effect. Exercise and maintaining a healthy weight have been shown to reduce risk, but what you eat seems less critical.

I agree that it may be tempting to cling to food as protective and/or curative. After all, when cancer takes so much from us, there is a desire to control the factors that we can — including what we eat and drink. I can’t tell you the number of women I know whom, at the time of diagnosis or the completion of treatment, decide they will eat “clean” or “healthy” and are right back in their old ways within months. During the acute phases of surgeries, chemotherapy, and/or radiation there can be a desire to take fear and channel it. By controlling what we ingest, we must be controlling what our body does and what happens to cells, right? Dr. Love reports that this is not as strong a case as one might think.

In my own opinion, if what we ate and drank were that instrumental in determining who got cancer and who had a recurrence, we’d have a cure by now. This is not to say that we aren’t learning more about risk factors and how certain foods can affect likelihoods of getting certain cancers. But for now, we do not have the scientific evidence to support such cut and dry statments about causality with breast cancer.

She shows little insight in her post into the mental reasoning that women make when deciding their treatment options. In fact, I don’t care at all for the way she chides the reader that a diagnosis of breast cancer “is not an emergency” and we should not make a deal with the gods to exchange our breasts for a clean bill of health.

In essence, she suffers from what she has just taken us to task for… equating correlation with causation. After all, just because women want to get rid of their cancer and they opt for a mastectomy, this does not mean they are making the decisions with that tradeoff as their guide. In fact, more often than not, it’s not even necessarily a reduction in breast cancer recurrence that women are after. There are other things they do not want to go through: mammograms, MRIs, biopsies, waiting for test results… and in my case, radiation on my left side which could cause heart damage.

I quote Dr. Love at length here:

We use wishful thinking all the time when making treatment decisions. When a woman is diagnosed with breast cancer her first reaction—understandably since she is scared to death!—is to do anything she can to insure that she is cured and make the fear go away. This fear (accompanied by wishful thinking) often leads people to do things that are not supported by the science.

One example of this is the studies that show that the number of mastectomies for breast cancer has been increasing in the U.S. each year. This is not happening because doctors are finding bigger tumors, or because mastectomy is a better treatment. It is the result of wishful thinking: If I offer my breast or breasts to the gods, I will surely get my life back in exchange! If I have no breast tissue, I never have to go through this again !

In reality, a mastectomy never removes all of the breast tissue. (I am a breast surgeon, so I should know.) The breast tissue does not come neatly packaged so that it be easily removed, which is why there always is some breast tissue left behind in the skin, around the muscle, and at the edges. In reality, the local recurrence rate after mastectomy is 5 to 10% and the local recurrence rate after lumpectomy and radiation is 5 to10%! It is exactly the same! And the cure rates are the same as well.

The critical issue is getting the tumor out with a rim of normal tissue and dealing with any cells that might have escaped—which is what radiation, chemotherapy, and hormone therapy are for. It seems like the more radical the surgery the better the results should be . . . but that is really just wishful thinking!

The rollercoaster ride of cancer is not to be underestimated. Once a patient has a history of cancer, there will be frequent monitoring which brings not only potential additional radiation, but also the knowledge that if there is a question, more testing, including biopsies, will be needed. This emotional up and down means a woman must prepare herself each time that her cancer may have returned.

The main problem with Dr. Love’s piece is that she chides patients for making hasty decisions about their heath care. She reminds us that she’s a breast surgeon for thirty years, after all. And yet, with that experience and scientific background, she should know better than to lump women into one decision-making category and not divide them out based on demographic differences. Oncologists (surgical and medical) both make recommendations to patients based on many variables. Issues such as age, whether this is a first diagnosis of cancer, whether other cancers are in the patient’s medical history, grade of the cancer (how aggressive), what type (including hormone receptor status), and family history all come into play in medical decision-making.

Additionally, women may opt to have a mastectomy or double mastectomy for aesthetic reasons. Some of my initial decision to have a mastectomy on my right side was because I wanted my reconstruction to be symmetrical. After three children my breasts were looking their age. If I had a mastectomy on one side I would have needed surgery to reshape my breast to better “match” the breast that would be made with reconstructive surgery.

When confronted with breast cancer, patients get divided into two camps: there are those who want to do the most possible to treat it and there are those who want to do the least they can while still “taking care of it.” Factors of age, grade and stage of cancer, issues of radiation, reconstruction, BRCA-1 and 2 status and personality type all come into play. I personally believe that the ability to tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty is a key part of the decision-making process.

I don’t say I’m cancer-free: I never say that.

I never say a double mastectomy means I won’t get cancer again.

I know what I had.

I know what I did.

It’s about well-informed choices.

I know what might happen…

In the end, it’s not just about the statistics: it’s about the person.

October 18th, 2011 §

For those of you who missed it yesterday, click here to the USA Today piece that Liz Szabo did about the decision for some women with breast cancer to have a mastectomy.

Everyone was so supportive in sharing publication day with me… thank you. The enthusiasm from Facebook and Twitter friends was truly touching.

The kids feel like celebrities! The photo on the cover page of the Life section was huge and the photographer captured a great laugh with the kids. The children were so patient during the 1.5 hour photo shoot.

I’m still working on a big post with more about the subject of mastectomies for breast cancer. I promise to have that up as soon as I can.

The response was overwhelmingly positive but there were a few criticisms of my decision. Here is what I reply:

I don’t believe that my decision to have a double mastectomy was a guarantee that my cancer won’t come back. There was much I could not control about cancer; some of that uncertainty still remains. However, how you treat your cancer, live with it, and monitor it are things you can control.

The shame is that when observers (many whom have no direct experience with cancer) decide to be critical of people with the disease, survivors may be afraid to tell their stories. Cancer awareness– true awareness– can only happen when men and women with breast cancer feel comfortable enough to talk about their experiences, their choices, and their disease without fear of being challenged.

I will continue to tell my story.

June 3rd, 2011 §

More often than not, cancer creeps into conversations with friends. New friends, old friends.

I don’t think I’m obsessed with it. I don’t have to talk about it. Why does it come up?

Is there a cancer radar?

Is it just that when cancer folks are together we let our guard down to share?

Do we want to compare notes and try to get information from each other?

Probably all of the above.

Here’s also where I think it comes from: talking about illness is grounding. It puts the emphasis where it should be. I have many friends who have family members who either have had or currently have cancer. We’re a club. There is a support we can provide for each other, a language we can speak. Stages, grades, blood counts, oncologists, PET scans, MRIs, tumor markers… and on it goes. I really think I should get credit for CSL… cancer as a second language.

I like people who “get it”; I find more and more that I am naturally drawn to them. I’m rarely surprised to find that new friends of mine have had some type of hardship in their lives.

Maybe it’s just that more and more people have “something” in their life story.

Maybe those are the people I gravitate to.

Maybe they are drawn to me (or the “vacuous people need not talk to me” sign I have on my back scares others away).

It’s not that I don’t like talking about shoes or The Bachelorette or movies. I do– a lot. And I actually do think they matter. It’s important to have a break from the heavy, serious stuff. Some people think that the small stuff is all there is– that it matters. Those people are hard for me to take.

One day, shortly after I was diagnosed, I sat watching my son take a tennis lesson. I was still numb and reeling from the news that I had cancer. I hadn’t started chemo, and was still awaiting surgery. I knew what I was facing: double mastectomy and chemo. But to the outside world I looked totally normal; no one would know what news I had received.

There were two moms sitting near me chatting loudly while their kids had their lesson. These were the days before the recession, when women in my town were flush with cash, and living high on the hog. They were talking about vacations. “I just can’t decide where we should go for vacations this year,” one said, “John has so many vacation days it’s going to be hard to use them all. We could go to Switzerland again. But that’s kind of boring. And there’s the Caribbean. But I kind of want to do something different. What do you think?” she said to her friend.

I know what I thought. I thought someone needed to hogtie me to the chair before I punched her out. That was a problem? It was one of the few times I really wanted to say “Lady, let me tell you about a problem.” But I didn’t.

Why?

Because maybe her mammogram was the next day.

Maybe she was a day from being told there was something suspicious on it.

Maybe she was a week away from having a biopsy.

Maybe she was a month from having a double mastectomy.

Maybe she was six weeks from starting chemo.

Maybe she was just about to learn the lessons I was learning.

May 18th, 2011 §

A few weeks ago I was talking with a friend about our blogs. She said that she never writes about her husband; some readers didn’t even know she was married. I don’t directly write about my husband Clarke often. I’ve written endlessly about his mother Barbara’s sudden death in a car crash in 2009 (if you want to read more about her, please click on the tag “Barbara” on the lower right of the page) but not about Clarke. Clarke is private, and I respect the fact that he doesn’t want to write or discuss topics that I do.

Clarke wrote a piece that I treasure. In 2009 he nominated me as a “Brave Chick” for a website that celebrated women who had tackled adversity (www.onebravechick.com). The interesting thing to me as I re-read the essay now is how much more has happened since then. We’ve had many medical and emotional challenges since this letter was written. I like to think that the seeds of strength were sown during some of these experiences.

I am re-posting this today not to celebrate myself, but rather to celebrate my husband. We are a team in this thing called life and I couldn’t do it without him. I hope I will get him back here on the blog sometime to write about some more of the issues we have dealt with; I think hearing it from his point of view might be helpful for some readers. But for now I will let his words sing, and hopefully honor him by doing so.

…………………………………..

“The bravest sight in the world is to see a great man (or woman) struggling against adversity.”

-Seneca

“Let us do our duty, in our shop in our kitchen, in the market, the street, the office, the school, the home, just as faithfully as if we stood in the front rank of some great battle, and knew that victory for mankind depends on our bravery, strength, and skill. When we do that, the humblest of us will be serving in that great army which achieves the welfare of the world”

-William Makepeace Thackeray

My wife Lisa and I met for the very first time at the George Foreman / Evander Holyfield fight in the spring of 1991 when, in a scene straight out of Rocky, a forty-two year old Foreman went the distance with the undefeated Holyfield. We met again at a Halloween party later that year and began dating. We got engaged in 1995 and married in the summer of the 1997. Over the course of our 18 years together and in particular the last three, it has become clear to me that my wife possesses more than her share of courage.

As with any 18 year period we have had our ups and downs together but mostly it has been up. We have three beautiful and intelligent children, loving and supportive families and great friends.

In the grand scheme of things, our life together was pretty smooth which is why I think we were completely unprepared for what the last three years have brought us. In August of 2006 we learned that our five month old baby boy was born with a condition that required immediate open heart surgery. He also had complex problems with his cervical vertebrae and the muscles of his hands that would require a significant ongoing investment of time and energy in medical care and therapy.

Since Lisa is at home with the kids when I’m at work, the day-to-day heavy lifting of running the house and managing the often crazy logistics of our lives naturally fall to her. In addition, because she is the medically savvy one in our family (her father is a surgeon and her mother is a psychologist), Lisa ended up quarterbacking and supervising Tristan’s care which included (and still does include to some extent) coordinating treatment with four or five different specialists (neurologists, pulmonary specialists, pediatric cardiothoracic and orthopedic surgeons, etc.) in three different cities. Juggling all of those competing priorities was extremely challenging and time-consuming. It seemed like fate was piling on hardship in January of 2007 when Lisa was diagnosed with Stage II breast cancer.

Lisa spent much of 2007 aggressively treating her cancer with a double mastectomy and chemotherapy. I’m sure many women who read your website are acquainted with the harsh reality of how tough a cancer treatment regimen can be on one’s body and, just as importantly, one’s psyche. I must confess that I wasn’t really prepared for what was to follow. Like many things, cancer treatment seems much simpler in the abstract or on television than in the messy reality of real life. It is a process where you are forced to make life-changing and often heartbreaking decisions while in possession of only limited information all the while dealing with the physical, mental, and emotional side effects of disease itself and the treatment. If adversity is the test by which character is revealed then I’m proud to say that my bride has passed her personal test with flying colors.

At least by the romanticized ideals of literature or history you don’t get to see real bravery very often when you live in Darien, Connecticut (braving the long lines at the local Starbucks doesn’t really count). However, there was something quietly heroic in how Lisa handled the myriad of issues she was dealing with in a thoughtful and calm (with some exceptions) manner all the while taking care of the thousand little details that go along with being a mom to a young family. No matter how much personal pain she was in, the kids’ lunches got made, their homework got done, their boo-boos got kissed, and their very real fears addressed and soothed even on the very worst days. Tending to young kids isn’t easy on your best day but being able to do so and face the world in the midst of cancer and chemo and all that implies is something else altogether.

Looking back, the amazing thing to me is how little impact the whole period had on our children; that speaks to how much of her energy and force of will Lisa put into ensuring that that was the case. We had lots of help from our families and our amazing group of friends, but at the center was Lisa getting up each day and doing her best to move forward with grace and determination (kind of like a 42 year-old George Foreman coming out of his corner, taking his licks and getting in some good shots of his own). In my book, that is all any of us can really expect of ourselves and defines what bravery is all about. When my test comes, I hope I do as well and face up to it with as much strength as Lisa did.

A friend whose wife had just gone through the breast cancer experience told me when I learned about Lisa’s diagnosis “the thing about breast cancer (pardon another tortured sports metaphor) is that you never get to spike the ball in the end zone and say you are done. There is always something else.” I thought I understood what he was saying at the time, but I appreciate it much more now. Although chemo ended in the summer of 2007 and her breast reconstruction finished shortly thereafter, Lisa has been dealing with the often frustrating regimen of drugs and side effects that come along with being a cancer survivor. While things are certainly better than they were, it has been a constant challenge and adjustment for both of us.

As I said earlier, one of the most difficult things about having cancer, even a cancer that is as common and well known as breast cancer, is that you really don’t have any idea what is ahead of you as either a patient or a spouse when you begin the process. There are reams of data and academic studies available but despite that fact, it is difficult to distill and digest all of that into a coherent picture as to what you as an individual (or the spouse of one) will experience.

As part of her life as a cancer survivor, Lisa has taken it upon herself to make understanding the long road of treatment, recovery, and being your own best advocate a little easier for women who will face the same challenges she did. She spends hours and hours speaking to women in our community who are just beginning the process about what she has been through in the hopes it will help them be prepared. As an extension of those conversations she began writing (and later blogging) about her experiences and feelings about cancer and posting them on the web. She sometimes writes clinically about the nitty-gritty medical realities of treatment and recovery which are based on her personal experiences, extensive research of the available medical literature, and her own conversations with her doctors.

Other times she examines the darker, emotional, frustrating, and deeply personal places that being a cancer survivor can sometimes bring you as young woman and a young mom. Her writing is often beautiful and poetic and is always thoughtful and enlightening. She puts it all “out there” for public scrutiny. She posts regularly under her own name to help her fellow women (our moms and sisters and daughters) understand and deal with a path that all too many of them will walk down at some point in their lives. I believe this is noble and selfless and courageous.

So as a very small and modest way of acknowledging her daily efforts and recognizing her achievements, I would like to nominate Lisa Adams (age 39), loving wife, wonderful mother, caring friend, talented writer, and strong cancer survivor to be a featured brave chick. I would invite those members of your community who are interested to check out her writing at lisabadams.com.

Thanks for your time and dedication to Brave Chicks everywhere.

Clarke Adams

July 7, 2009

March 29th, 2011 §

I get asked a lot about health insurance claims. Having had many different diagnoses, surgeries, and procedures I have became all too familiar with interacting with insurance companies. In the last few years my diagnosis of breast cancer and the almost simultaneous diagnosis of our son Tristan with congenital spine and hand abnormalities has meant a level of paperwork, claims, and appeals I could never have imagined.

Navigating the maze of medical care and health insurance has become second nature to me. I think I’ve resisted writing this piece because initially I thought there wasn’t much to say. Having worked on this piece for weeks now, I realize the opposite is true: there is too much to say. Because each case is different it’s very hard to offer advice on what you, the reader, should do. But I’ve decided that’s the beauty of the blog format: I don’t have to cover all the bases. I don’t have to have all of the answers. I just need to do my best to help. And so today I’m starting to tackle this beast.

I’ve had many requests to write pieces about how to win against health insurance companies and many have suggested I go into this as a profession. I’m not sure about that one but I am definitely willing to share some of the insights I’ve learned throughout the past few years. I do think my upbringing in a medical household (my father was a cardiothoracic surgeon) helped familiarize me with medical terminology and how to correctly present a medical history. In addition to my tips you may be interested to read Wendell Potter’s recent advice in The New York Times: “A Health Insurance Insider Offers Words of Advice.”

Don’t take ‘no’ for an answer

The first piece of advice I have is simple: don’t take no for an answer. The fact your claim was denied is the starting point not the ending point. Insurance companies count on the fact that a large percentage of subscribers will receive a denial and either 1) forget about it, 2) intend to file an appeal but not follow through, or 3) incorrectly file the appeal paperwork (see Potter’s article, above). In any case, if they send you a claim denial and you don’t follow up for any reason, they win.

Always appeal

If you receive a rejection to a claim you feel you are entitled to always appeal. When I receive a claim denial I roll my eyes, roll up my sleeves, and say, “here we go again.” It’s what I expect, but it’s never the last word to me. Now, that is not to say that you always win– but it would take way more than one denial for me to accept that I’m not entitled to have a medical service covered. Persistence and determination are a large part of what it takes to win.

Physical (especially congenital) problems are easier to appeal than those related to developmental delays. I have little/no experience with appeals for diagnoses related solely to delays; while many of my general tips will still apply, more specific ideas will hopefully be available elsewhere online for those types of claims. I do know that when it comes to dealing with insurance companies those types of diagnoses are harder to quantify; this often leads to greater challenges with insurance appeals. In my experience, if the delays can be linked to anatomical problems, orthopedic issues, or diagnoses that can be validated with tests like MRIs or CTs, the case will be easier to justify.

Insurance companies must give you a reason whey they are denying a claim. Most often this reason is that 1) the treatment is experimental or investigational, 2) the treatment is not medically necessary, or 3) the treatment is not the standard of care.

In our case, initial denials have most often been because it wasn’t considered medically necessary.

Show the progression of the situation and how options have been exhausted

I always try to base appeals on the phrases “medical necessity” and “medically necessary.” When you document a surgery or service that you or your family member needs:

Be clear how it is necessary to daily functioning.

Describe what will happen if what you are asking for doesn’t happen.

Be sure to tell what you have tried already, and what has failed.

Show how your diagnosis and treatment history has brought you to this place–how there is no other reasonable option to what you are asking for (or how the alternative is not preferable).

Be complete but don’t ramble.

Be sure to include diagnosis codes and treatment codes (your medical professional will provide these).

Doctors’ offices don’t always have the final say

I should point out that a doctor’s office may tell you that you will have to pay out-of-pocket. They may tell you that they have tried to get your service covered, it was denied and therefore this is the last word. It’s not. For example, my neurologist’s office tried to get my Botox injections covered. Their office appealed the first rejection. They were again denied. They told me that there was “nothing else they could do”; I would have to pay.

Undeterred, I asked for copies of my medical records. I called my insurance company and asked what I needed to do. Despite what the doctor’s office told me, I learned that patients often have a separate appeals process available to them. While physicians’ offices can often get services covered and can be very helpful in knowing what’s been a successful method of appeal in the past, they are not the only way to get services approved. In a case like this there is actually a financial disincentive for them to have insurance cover it; therefore, they may not be as aggressive as you will. What does that mean? If I had paid out of pocket they would have received almost three times the amount of money that they receive when compensated by my insurance company directly.

When the office tried to get the injections covered, the insurance company denied the request on the basis that this was an experimental treatment– not FDA-approved for this use. I provided medical history sheets from my medical file. I documented every drug I had take until that point to try to prevent migraines and the dates I took them. I explained the medical condition/situation that resulted when I had migraines. I told them how the neurologist felt the Botox might help me. I included the original letter he had written to the insurance company. I explained that if they didn’t cover this treatment a more expensive, more medically damaging situation would result– this would mean more claims and more expense for the company. In the case of the migraines I documented how much my “rescue medications” were costing them per month and how a reduction in those would easily pay for the Botox I was asking for. I showed through my history with the numerous failed attempts with other drugs that the situation had not improved and in fact the side effects from those drugs had been debilitating. I also showed the literature about preliminary success in clinical trials with Botox and my neurologist’s observations about its efficacy in others and the potential efficacy in my case. I explained I had no other choice, and while it might be not-yet FDA approved, Botox was actually on the verge of receiving such approval (I was proved right when it did receive approval for this purpose less than one year after my request).

Include all relevant information and send appeal within the required time period

This letter of appeal doesn’t need to be 3 pages long. In fact, even in my most complicated appeals I didn’t write more than a page or two at most (plus the inclusion of the supporting documents). Be sure to appeal/respond within the time frame they dictate. In the letter be sure to include:

your contact information, subscriber number, and the doctor/hospital/treatment facility information

the case reference number that they provide

all relevant diagnosis and procedure codes

Ask doctors and staff for assistance, documents

Do not be afraid to ask your doctor and his/her staff for help: what tactics have they found useful? If there are multiple codes that apply which ones are the best to use? Do they have any sample letters for appealing? What has their experience been with your particular health insurance company?

Use the rejection letter as the foundation for your appeal

Take the rejection letter you received and read it carefully. Don’t just react with “it says no” and throw it away. It is vital; in it, the company must tell you why they are rejecting your claim (usually one of those three reasons I mentioned at the outset). This is the key to your appeal. You must address this issue. They’re telling you the basis, you need to fight based on that. Be thorough but don’t get off track.

Another good example of persistence in appeals came with a corrective band we used for Tristan’s quite-misshapen head (diagnoses of plagiocephaly and brachiocephaly). The facility we used for the DOC band told us that insurance claims were most often denied for this service. Indeed, the first claim was denied; they said the “helmet” to correct his misshapen head was for cosmetic reasons only. I appealed. I explained that because of his neck abnormalities the head deformity was an inevitable result of having his head fixed in one place. Because he was unable to move his head properly he had this inevitable result of a physical abnormality. I ended up having two helmets approved for coverage. Had I accepted the facility’s statement that “insurance companies usually don’t pay for this” or my first rejection letter from the company, we would have had to pay in full for both helmets. I should point out that I’ve seen success getting this particular service covered even when the plagiocephaly was not due to a unique condition like Tristan’s when the subscriber persisted with the appeal process.

You can appeal more than just a denied claim