November 7th, 2014 §

This week has been one of disappointment and adjustment. I met with the interventional radiologist on Wednesday afternoon to discuss what can be done for the metastases to my liver and what options are available. While chemotherapy has done a remarkable job in clearing up the cancer in my chest (it is resolved; if there, is small enough that it doesn’t show up on the scan), there are metastases to my liver that are chemotherapy-resistant. This means they have grown despite the fact that chemo that has worked well in other areas of my body.

This week has been one of disappointment and adjustment. I met with the interventional radiologist on Wednesday afternoon to discuss what can be done for the metastases to my liver and what options are available. While chemotherapy has done a remarkable job in clearing up the cancer in my chest (it is resolved; if there, is small enough that it doesn’t show up on the scan), there are metastases to my liver that are chemotherapy-resistant. This means they have grown despite the fact that chemo that has worked well in other areas of my body.

Unfortunately, what I learned while reviewing the scan with him is that I don’t just have two tumors in the liver. Instead there are actually many tumors in my liver, with those two being the largest. The fact there are so many tumors is why I am not a candidate for external beam radiation or other non-invasive treatment.

So far I am still a candidate for the Yttrium 90 radioembolyzation procedure where radioactive beads are inserted via a catheter snaked up through the groin into the hepatic artery and subsequently “feed” the tumors radioactive material as the beads work their way into the liver.

It will take three separate procedures spaced about two weeks apart to get this done. I will start the first week of December and finish in January. The first procedure involves mapping things out (in essence, a “dry run” where mock beads are inserted) and the next two are actual placement procedures. This is all a joint approach between interventional radiology and nuclear medicine. Before I start I will need a CT angiogram of the liver and a PET scan. After treatment I will have to monitor progress with PET scans every three months.

In the meantime we need to start on a new IV chemotherapy right away to try to see if we can find a chemo that will work on the liver tumors. We have no way of knowing if we will find one or what it will be. Right now my oncologist is eyeing Cisplatin, a platinum-based chemo like the Carboplatin I was on this summer. We will make the decision by next week and begin then.

The liver situation is serious. The cancer is growing rapidly there and we need to get it under control. Results of using Yttrium 90 for breast mets is pretty good, definitely good enough to proceed with it. To be honest, it is not a choice about whether to do it (I’m not at a point where I would consider doing nothing and stopping treatment, I realize that proceeding with any type of treatment is a choice in and of itself). There aren’t other options to treat these in a “batch” way.

So, there is a lot of adjustment right now. I feel sadness, disappointment, and anger that chemo has worked so well in some areas but the liver has been resistant. Things change so fast with this disease. One day things are relatively stable and within weeks they can be spiraling out of control.

As always, I will continue to educate and do what I can to show what my life with metastatic breast cancer is, what life with the disease can be.

For now, I will begin a new chemo and proceed with plans and pre-surgical testing for December. I’ve appreciated the emails and comments so much and I thank you all for your concern and wishes. I am sorry that I can’t respond to them all individually.

October 17th, 2014 §

My last post (“The Hardest Conversation”) showed you what a conversation with my teen daughter was like when we talked about my diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer in 2012. Today I wanted to share a conversation with my youngest child (now 8) that happened last year so you can see the variation in what their concerns were and how I dealt with each one.

As always, with cancer, age-appropriate explanations are important. Another vital piece of advice I’d like to share is that with all children, but especially young children, it is important to talk more than once about the topic. At the end of the first conversation I recommend asking young children, “Can you tell me what we talked about today?” to see if they have absorbed the most important pieces of information and that these pieces are correct. A day or two later it is always a good idea to ask, “Now that you’ve had time to think about our chat, do you have any questions?”

The following post was written in late 2013 on the eve of the surgery to put my medi-port in.

………………………………………………

“Why do you have to have surgery tomorrow?” seven year-old Tristan asks from the back seat after we drop off his 11 and 15 year old siblings this morning.

“Why do you have to have surgery tomorrow?” seven year-old Tristan asks from the back seat after we drop off his 11 and 15 year old siblings this morning.

“Because I need to have something put in my body called a port. It’s a little container made of something cool called titanium that lets the doctors put some of my medicines into my body in an easier way.”

“Can you see it?”

“Yes, you will be able to see that there is a lump under my skin, about the size of a quarter. But you will only see the lump. You won’t see the actual thing because that will be inside my body. You know how I have the scar on the front of my neck? It will be like that, here, off to the side, same size scar but with a bump under it.”

“Is it like the bubble I had on my neck when I was a baby?”

“Well, that was a skin tag, so that was a lot smaller. And they were taking that away. This is something they are putting in to help make it easier to get some of my medicines. And you know when you go with me and I have blood taken from my hand? Well now sometimes they will be able to just take it from there instead. So it helps with a few jobs.”

“Will you have it forever or do they take it out when your cancer goes away?”

(Driving the car, trying to keep tears in check, knowing this is a vitally important conversation. I’ve explained this to him before but I know it’s hard for him to understand.)

“Well, honey, remember I had cancer when you were a baby? Well, this time the cancer is different. A lot of the time you can have cancer and the medicines and surgeries make it go away and it stays away for a long, long time. Maybe even forever. Sometimes any cancer cells that might be left go to sleep and just stay that way. Sometimes you have bad luck and they wake up. Mine woke up after six years. And now the cancer cells are in places that I won’t be able to get rid of them all for good. I am always going to have cancer. This time my cancer is the kind that is always going to be here.”

“You’ll always need medicine. And the thing they are putting in?”

“Yes, honey, I will always need medicine for my cancer. And I will probably need to have the port in forever too.”

Long silence.

“I am glad you are asking me questions about it. I want you to always ask me anything. I will try to explain everything to you. I know it’s complicated. It’s complicated even for grownups to understand.”

Long silence.

“Mom, did you know people whose eyes can’t see use the ridges on the sides of coins to tell which one they are holding? So if you have a big coin with ridges that person would know it is a quarter?”

“That makes sense. How did you learn that?”

“At school. And so if it’s smooth you know it’s a nickel or penny. It’s important that they know what coin it is.”

“I think you’re right. That is very clever.”

( I stay quiet waiting to see where he will take the conversation next.)

“Remember when my ear tube fell out and was trapped in my ear and the doctor pulled it out and I got to see it? It was smaller than I thought it would be.”

“Yes, I thought the same thing.”

“I really wanted to see it. I wanted to see what it looked like.”

“Me too.”

“Can you show me a picture of it?”

“Of what?”

“The thing for tomorrow.”

“The port?”

“Yes. Or don’t you know what it will look like?”

“I know what it will look like. Sure, I will show you on the computer after school.”

“Okay.”

“It’s time for school but I am glad we talked about this. I want you to keep asking questions when you don’t understand something. I love you, Tristan. I hope you know how much. I know this is hard for all of us. I wish it were different. But we are going to keep helping each other. And talking about all of this is good. We can do that whenever you want.”

November 26th, 2013 §

On Friday morning after I sent our three children off to school I traveled to Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) to have a port implanted. My first appointment of the day was at 10:15 to have an electrocardiogram (EKG/ECG). MSK requires an EKG on one of their machines within 48 hours of the port procedure. It takes longer to find the bathroom than it does to have this test done. Electronic leads are attached with sticky sensors to specific points all over your body and hooked up to a machine. After about one minute of recording you are done, and the sticky round patches and the attached wires are removed. Easy as can be. The test measures the electrical activity of your heart to make sure it is normal. I won’t go into details on this test because it’s such a piece of cake and so common.

On Friday morning after I sent our three children off to school I traveled to Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) to have a port implanted. My first appointment of the day was at 10:15 to have an electrocardiogram (EKG/ECG). MSK requires an EKG on one of their machines within 48 hours of the port procedure. It takes longer to find the bathroom than it does to have this test done. Electronic leads are attached with sticky sensors to specific points all over your body and hooked up to a machine. After about one minute of recording you are done, and the sticky round patches and the attached wires are removed. Easy as can be. The test measures the electrical activity of your heart to make sure it is normal. I won’t go into details on this test because it’s such a piece of cake and so common.

After that test was complete (by 10:08) I went to a different floor in the same building to the Interventional Radiology department. There, a friendly team checked me in and sent me to the waiting room, a large attractive area brimming with patients and family members. After a little while a woman called my name and I was taken back to be prepped for surgery about 30 minutes before my scheduled 11:15 arrival time. I will say that for every test and procedure I’ve had so far at MSK’s main hospital they have been on early or on time. This has been a pleasant surprise at such a large medical center.

Once we reached a small prep room a very cheerful nurse gave me a garment bag to store my clothes in and I changed into a standard issue hospital gown with a thin navy blue bathrobe to wear over the top. She weighed me, measured my height, and reviewed my medical history. This was the first surgery I had at MSK so I had to review my surgeries and allergies along with current medications, etc. They wanted to do another pregnancy test but I refused on the grounds that I had an oophorectomy and the test was unnecessary. Because the surgery had not been done there they didn’t have the exemption in my file. They confirmed that I had not used any blood thinners (including medications or pain remedies that can act as blood thinners) in the days prior to surgery.

I then met the surgeon for the first time and he and I discussed the precise placement site of the port and also the ramifications of my sensitivity to adhesives. Usually it’s not too much of an issue but for this procedure the surgeons usually close the incisions with Dermabond (skin glue) and my skin cannot tolerate that. Sutures would be used instead.

The surgeon pinched the skin between my collarbone and the top of my breast implant and said that there was enough tissue there to use the preferred port, called a MediPort or PowerPort. Each person has a different amount of fatty tissue in this area, and a mastectomy may affect this as well. Age, body type and other factors can affect which model of port can be used and where it will be positioned. Obviously, children and people using a port for only a short period of time may have different limitations and needs. There were a few times during the day when someone said to me, “You’ll just have this for a while and won’t even know it’s been there after it’s gone.” They assumed that I would only need it temporarily. “It’s here for good,” I said more than once.

There are many different kinds of ports. They have changed a lot over the years. The one I have is quite small and is triangular in shape. This shape is an indicator that the port can be used for injections of contrast dye (these are called “power-injectable”) in addition to being used for blood draws and any future IV chemo. The power-injectable feature means that when I go for CT scans, bone scans, or PET scans, the technician can inject any dye that might be needed for that test into the port rather than having to use an IV line into my hand or arm. This is one reason I decided to get the port. Being in clinical trials now means frequent blood draws and scans.

The nurse started an IV in the holding area and I was wheeled through a maze of hallways until we stopped outside the operating room. I got off the gurney, walked into the OR, and hopped onto the table. After a lot of prep including hooking me up to monitors and draping and cleaning the area, they finally pushed Fentanyl and Versed into my IV. I didn’t actually go to sleep but probably could have. They numbed the two incision areas with local anesthetic and after about 15 minutes including a few periods of tugging and pushing it was over. I’m going to just link to the actual description that MSK gives about the procedure itself. I’m not sure I can explain it any better than they do.

I stayed in the OR for about ten minutes and then was wheeled to a very small private recovery room where I stayed for about an hour. The one surprise is that in the Interventional Radiology department’s recovery area at MSK they do not give you anything to eat or drink after procedures. So I needed to wait until I left to have anything (tip: if you are going to have a port placed, tuck a snack and drink in your bag. After fasting until the procedure you will want something convenient to eat and drink afterwards and radiology departments might not provide them the way that surgical recovery areas often do).

My husband was able to join me in this recovery area after I was settled. A nurse reviewed my discharge instructions. I needed to wait slightly longer to get the incisions wet than usual because I did not have the Dermabond. Usually it’s a 1-2 day wait. I was quite sore immediately after and was glad I had put a cushion and pillow in the car. If your port is put on the right side, as mine is, the passenger side seat belt will not be pleasant so I recommend bringing a padded seatbelt cover or other method of cushioning the strap. I was quite sore for about 24 hours, but quickly that shifted from being generally aware of the pain to being very localized and only when using that arm. That quickly became localized discomfort if touching it. Today (three days later) it’s still sore to the touch but otherwise not bothersome. I did not use any pain medication.

The port is much smaller than I would have thought. It’s placed so low that it won’t be visible in a tank top. The surgeon was very careful to try to pinpoint a location that would be cosmetically most appealing which I appreciated since this will not be temporary. Eventually I will need IV chemo and this will be used for that as well. For now there are two red incisions but I know those will fade. They are far more visible than the port, a bump under the skin the size of a quarter.

I will not be able to use the port for blood draws that I do near my home and many people are not aware that not all phlebotomists can access the port. Only certain people (most often at hospitals and oncology offices) can access the port because you need special training and also special equipment. In addition, if you do not use the port for a period of about 30 days you must go to have it flushed (with saline and Heparin) to prevent clotting. It only takes a minute to do that.

I’m happy to answer any questions that readers have about the port or anything I missed in the description.

…………………………………

Today I was back at MSK for my regular clinic day for Cycle 2, Day 1 of my clinical trial of Genentech GDC-0032 + Faslodex. I met with a nurse first who checked my weight, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, did a physical exam, reviewed my side effects (I won’t go into those in this post). Next I met with the Principal Investigator on the trial who is the one in charge of my care during this time. I gave her the four remaining pills of my 30 day supply (two each of 1 mg and 5 mg capsules of GDC-0032) and signed and turned in my medication log which lists what time I stop eating each night and what time I take my pills each morning. We discussed scheduling for the month which includes my CT scan three weeks from now where we will get our first look at what, if any, effect the drug combination is having on the cancer.

Next I went to the chemo suite to get my Faslodex injections and have my blood drawn as required by the protocol. I had a different nurse this time from the last two times. I told her that I had a new port and asked her to explain the process for the draw now. She warned me it might be sore as she palpated it to find the right spot to insert the needle and also said the actual needle stick might be a bit more painful today depending on the exact location of my incision.

We each needed to put masks on to cover our nose and mouth during the blood draw to minimize the chance of infection. She gently felt for the circular center of the port where the reservoir is and inserted a special needle to access it. It was a bit tender but certainly not at all more painful than my usual stick on the back of my hand. It really was just a second and it was great to know there was no chance of “failure”… blood would flow! And it did. Six tubes were done quickly and then she flushed the port with saline and Heparin to prevent clotting. The needle was removed, a gauze and paper tape bandage applied (no adhesives for me) and then we removed our masks. Easy and no anxiety. These steps must be taken every time.

Next it was time for the two nasty Faslodex injections. As I’ve written before these are two jumbo intramuscular injections, one in each butt cheek. The nurse kept apologizing and saying how she hates to give them because they’re just so big and painful. They are always very sympathetic when administering these. Today’s were painful, I think the worst of the 3 rounds I’ve had. I think it’s just chance about where they hit and also that I’ve had to do them every two weeks this month during the loading phase. Now I will only need them every month so there is longer recovery in between from the soreness and muscle pain. I find that a heating pad is the most comforting way to ease the pain, I’m definitely getting used to it and also knowing what to expect.

Once done I stopped into the pharmacy (right next to the chemo suite) to pick up my next month’s supply of GDC-0032. I needed to wait to take today’s dose until after my bloodwork. I took my pills with a glass of water while still standing in the pharmacy and noted the time in my new medication log. I would now need to wait one hour before eating or drinking (as I always do when I take my dose each morning).

I went down one floor to scheduling, made my next appointments, and was on my way about 2.5 hours after I first walked back to the exam room. I met a friend for breakfast and had that blissful first cup of coffee at precisely the time allowed. I took the train home, and fell asleep on the way.

I’ll be back at MSK in two weeks for an appointment with the doctor and bloodwork. The week after that will be my scan and then I’ll be back again a few days before Christmas to begin Cycle 3 if all is stable.

If my cancer has grown (“progressed”) by 20% or more, however, the drug combination is deemed not working. I will stop the trial (and be dropped from it) and I will need to move on to something else. I’m already at work researching what that next choice should be.

…………………………………….

We are entering a fragile time of year. The holidays are difficult for many people. Some miss loved ones who have died. Some mourn their own lives, no longer what they were. Grief takes many forms. The pressure to create memorable and uplifting occasions can sometimes be oppressive.

Be kind to those who are struggling during this time; physical and mental illnesses can be especially difficult to manage. Understand that happiness and sadness can coexist. Reach out to others if you can.

Find a bit of beauty in the world. Share it. If you can’t find it, create it. Some days this may be hard to do. Persevere.

June 6th, 2011 §

The rest of my family is coming back today. After a week in Jackson Hole, Clarke and Paige and Colin will return tonight, just in time for Colin’s 7th birthday tomorrow.

The refrigerator has been really empty this week. With just a 2-year old and me, it doesn’t take much to keep us fed. So I took the opportunity this morning to clean out the refrigerator and freezer– really clean them. Take everything out, throw away all the junk, the ice cream that now is just ice crystals. I tossed all of those “placeholders” that you never eat, they just take up room.

As I sprayed a wonderful new lemon verbena spray on the glass shelves, I start contemplating this week. The last seven days were my week to recover from surgery (an oophorectomy), to get stronger, to close out my year. I know I made the right decision not to join my family in Wyoming this year. It’s been a reflective time, a time for my soul to be quiet and heal. I think it’s done that a little. I think another week might help. I’ve loved my one-on-one time with Tristan; we have a nice little routine going, and I feel like he’s grown up this week.

But as the new year starts, of course, we are pushed to reflect on ourselves, to make ourselves better in the next 365 days. We reflexively reflect on whether we’ve kept any of those elusive resolutions from the previous year. December 31st is supposed to bring “closure.” In the arbitrary distinction between one year and the next (after all, why is there really a difference between the last day of 2008 and the first of 2009 any more so than any other passage of midnight on any other day of the year), we are pushed to wipe the slate clean and start anew. As I cleaned the house this week, purging old canned goods, papers, clothing, and sprucing up the house I found I was instinctively doing this: “Out with the old, in with the new.”

This annual rehabilitation, then, is supposed to be psychological and physical.

Most of our resolutions are about ways we want to be better, inside and out: concentrating on the new and gaining closure on the past.

One of my dearest friends wrote to me in an email last week, “And yet, you can no more gain ‘closure’ on life-altering events than you can erase moments from your memory.” I read that sentence many times. It is beautiful, and true.

I remember well when my friend Alex’s father died of cancer almost 10 years ago. She was so busy with all of the things that needed to be done, the arrangements that needed to be made, and taking care of her mother who needed constant attention and support. I remember wondering when she was going to grieve. I worried that his death, and his absence from her life, would fester and haunt her.

As I scrubbed the refrigerator shelves this morning I realized that you never grieve the way you think you should.

No one really just sits alone and thinks about the tragedies that befall them.

It’s too painful, too powerful to take that in as one big gulp.

Instead, what we do is weave it into the tapestry of our consciousness.

We make it part of our daily life, quiet, but present.

Maybe at this time of year we reflect more than usual, and maybe that’s why the holidays are painful as we take stock of what we’ve lost during the year and what we’ve gained.

Where that balance lands says a lot.

A year ago I thought surely 2008 would be better than 2007. It really didn’t turn out that way. But I am doggedly optimistic even when I’ve been been proven wrong so many times. I do not believe that there is a “justice meter” in the universe that is going to now dump things on someone else and leave me alone for a year. But maybe as my own tapestry of consciousness keeps getting woven, it will be stronger and more resilient to keep me going this year.

At least I’m starting with a clean refrigerator.

originally written January 2, 2009. Modified June 6, 2011

May 1st, 2011 §

In the weeks before my surgery, I looked at pictures of double mastectomy patients on the Internet. I Googled “bilateral mastectomy images before and after” thinking I was doing research. I thought I was preparing myself for what was coming.

In reality I was trying to scare myself. I wanted to see if I could handle the worst; if I could, I would be ready. My reaction to those images would be my litmus test.

Some of the pictures were horrific. I sat transfixed. I looked. I sobbed. I saw scarred, bizarre, transformed bodies and couldn’t believe that was going to be my body.

Days later, when I met my surgeon for my pre-op appointment he said, “From now on, don’t look at pictures on the Internet. If you want to see before and after pictures, ask me– look at ones in my office. You can’t look at random pictures and think that’s necessarily what you are going to look like.”

All I could do was duck my head in an admission of guilt. How did he know what I’d done? I realized how he knew: other women must do this. Other women must have made this mistake.

The aftermath is terrible to me though not in the ways I’d anticipated. I have no sensation in most of my chest. I never will.

A major erogenous zone has been completely taken away from me. Yes, I have new nipples constructed, but they have no feeling in them; they are completely cosmetic. The entire reconstruction looks great but I can’t feel any of it. It does help me psychologically beyond measure to have had these procedures though.

Here I sit, two gel-filled silicone shells inside my body simulating the biologically feminine body parts I should have. And sometimes that thought is disturbing.

To be clear: I don’t regret having them put in. I’ve never regretted that. It was a decision I made, and made deliberately. I knew that reconstructing my breasts was the right decision for me. I’m getting used to them– I’m almost there.

I definitely don’t remember what my breasts looked like before. I only remember these.

I once asked my plastic surgeon to see my “before” pictures a year or two after my reconstruction was over. You know what? My “before” breasts didn’t look so great. In my mind they did.

In my mind, everything about my life before cancer was better.

But that’s not the truth.

My mind distorts the memory of my body before cancer. Then forgets it.

My mind distorts the memory of my life before cancer. Then forgets it.

With time, I can get used to a new self.

It’s like catching my reflection in the mirror: only lately do I recognize the person staring back at me.

For over a year the new hair threw me. It’s darker than I remember it being before it fell out. It’s shorter than it was before, too.

And the look in my eyes? That’s different also.

I just don’t recognize myself some days.

Sounds like a cliché if you haven’t lived it.

But it’s true.

April 15, 2009

April 28th, 2011 §

I almost stole it: the tape measure with the purple finger prints.

After all, my surgeon had left it in my room by accident. After he had marked me with his purple pen and left my room on his way to get ready for my surgery, he left it sitting on the counter by the sink. In my nervousness and tranquilized haze I didn’t see it until after he’d left. I figured I shouldn’t hold onto it as I was wheeled in (“Who knows what germs lurk in tape measures!” I thought), and that if I gave it to a nurse it might get misplaced. So I shoved it in my bag of personal belongings knowing I’d be in for an office visit shortly after surgery.

I actually forgot about it during the days I was home after my two-day hospital stay. The drugs, the pain, the shock of my breasts gone and numb chest filled with temporary tissue expanders were all I could think about.

I forgot all about it as I was shuttled around for weeks unable to drive. I wasn’t living my normal life, my normal routine. I wasn’t carrying my purse and keys daily. I was living in pajamas and constantly trying to adjust to a new body once the drains were removed.

Then while I was looking for my keys a few weeks after my operation I saw it: the tape measure.

The yellow fabric one with the purple fingerprints up and down its sides.

The one.

The one that had measured and determined where my body was to be cut.

It was there in my bag.

There wasn’t anything particularly special about its practicality; it was just a tape measure.

Just like the ones I have sitting around with all of the odds and ends that inhabit kitchen drawers.

But that doesn’t capture the social meaning of it.

It wasn’t just any tape measure. It was mine.

But it wasn’t just mine, I argued with myself—it wasn’t a personal momento for me.

For a moment or two I wanted it.

I needed it,

as if to remind myself what had been,

of what I had been.

It wasn’t mine, I thought– it was his.

But more than that, it was theirs; it was ours… the other women who had needed it.

Now I was one of them. It was a shared history we had: strangers who had endured the same surgery, whose faces and names I would not know.

We were bound together by this object which had literally touched all of us.

And then I realized it was my responsibility to give it back.

Not for the obvious reason that it didn’t belong to me.

But as usual, I thought of the other women: the ones who didn’t even know they had cancer,

the ones who were going about their normal lives that day, and in the days ahead, only days or weeks or months from learning the life-altering news that would change their lives.

I felt giving back the tape measure would be my way of being bound to them, of saying “I know what you have ahead of you. I’ve come from there, and we are in it together.”

And so when I went to one of my office visits, I took it out of my bag and casually handed it to my surgeon. “You forgot this in my room when I had my surgery,” I said. He thanked me and said “I wondered where it had gone to.”

Little did he know the journey it had taken.

January 10th, 2011 §

January 30, 2009

I had two surgeons that day:

one just wasn’t enough for the job.

The surgical oncologist would take away,

the reconstructive surgeon would begin to put back.

Before I headed off into my slumber,

I stood as one marked me with purple marker.

He drew,

he checked,

he measured.

And then a laugh,

always a laugh to break the tension:

Surgeons must initial the body part to be removed to ensure

they remove the correct one.

But what if you are removing both?

How silly to sign twice,

we agreed.

And yet he did,

initialing my breasts with his unwelcome autograph.

The edges of the yellow fabric measuring tape he used

had purple fingerprints up and down their sides;

use after use had changed their hue.

And now it was my turn to go under the knife–

a few more purple prints on the tape.

I got marked many a time by him that year.

Endless rounds of

purple dots,

dashes,

and lines

punctuating my body

with their strange, secret blueprint

only those wearing blue understood.

We stood in front of mirrors

making decisions in tandem

as to how my body should and would take new shape.

Two years today and counting.

Moving forward.

Sometimes crawling,

sometimes marching,

and sometimes just stopping to rest

and take note of my location.

Numb inside and out,

but determined.

Grateful,

hopeful,

often melancholy.

Here comes another year

to put more distance

between

it and me.

Let’s go.

December 30th, 2010 §

One of my favorite romantic movie moments occurs between Denys (Robert Redford) and Karen (Meryl Streep) in the movie Out of Africa. The two lovers are out in the African desert at a fireside camp. Karen leans her head back into Denys’s hands. He washes her hair gently, then cradles her head in one hand and pours water from a pitcher, slowly and gently rinsing the soap from her hair after he’s done washing it. It’s a tender moment, to me utterly soft and sensual.

Before I left the hospital after I had a double mastectomy, the staff told me I might not be able to lift my arms over my head. With both sides affected, they said, I’d likely be unable to wash my own hair.

Recovery is slow in the week after surgery. A clear thin tube (like aquarium tubing) is literally sewn into a small hole in the skin under each arm. It carries excess fluid away from the mastectomy site as it heals. Fluid is collected into a small “bulb” and measured every few hours. After certain medical criteria are met, the drains are removed, the incisions sewn up, and then you can finally take that longed-for shower. Eight days after the surgery I received the all-clear. As any mastectomy patient will tell you, the day you get your drain(s) out is a great day.

Only then did I try to lift my arms. And hurt it did. I tried to shrink down into my body. I tried to be a tortoise withdrawing my head back inside my shell, shortening my height so I wouldn’t have to lift my hands so high to reach my hair. It was a painful challenge. I worked up a sweat trying to get my fingers to touch my scalp. I knew it was a questionable proposition. But I thought I could do it.

I thought about that scene— that romantic tender scene from Out of Africa. And I started laughing. I laughed and I laughed and tears came down my face. That cry hurt. It was one of those “I’m laughing and I’m crying and I’m not sure if it’s funny or sad or both and I don’t want to think about it so I’ll just go with it and I hope I’m not on Candid Camera right now…”

I was laughing at the absurdity of it. Here I was. It was my chance to get Clarke to wash my hair. My big fantasy moment. I was going to be Meryl Streep and he was going to be Robert Redford and he was going to wash my hair. Except I couldn’t move without pain. And I certainly wasn’t feeling romantic. I had just had my breasts removed. And I had these weird temporary breasts (tissue expanders) in their place. And my chest was numb. And my underarms hurt from having tubes in them for a week.

Because I hadn’t properly showered I still had purple Sharpie hieroglyphics all over my chest. And I had no nipples. And I had big scars and stitches in place of each breast. And a small angry scar with stitches under each armpit where the drain had just been removed. Let me tell you… this was clearly not how I envisioned beckoning my loving husband to come make my little movie scene a reality.

Now, don’t get me wrong. Had I called him from the other room, he would have done it in a second. He would have been there for me, washed my hair, and not made me feel the bizarre, odiferous (!) freak I felt at that moment. And I would have loved him for it. But I did not want him to see me like that.

In that moment I had a dilemma. What kind of woman was I going to be?

What kind of person was I going to be with this disease from that moment going forward?

I was going to push myself. Do it myself.

I wasn’t going to be taken care of if I could help it. I knew I was going to have trouble asking for help, have trouble accepting help. I knew these things were going to be necessary. But I also knew they were going to cause me problems. That’s the kind of person I am.

I knew asking for and accepting help were actually going to make me feel weaker than I was already feeling. And it was only the beginning. I knew these actions were going to make me feel weaker than I knew I was going to get. I wanted to do everything myself for as long as I could. That was what was going to make me feel alive: doing it myself.

I am not sure I did the best job washing my hair. I probably missed a spot or two. But I did it. And I didn’t ask for help.

Granted, it was something small.

But in that particular moment, on that particular day, that particular act gave me a feeling of pride as big as anything else I could have possibly accomplished.

a postscript: I wish I had been more accepting of help in the early days. I wish I had not seen it as a personal “weakness” the way that I express here. I don’t want to change what I wrote then, but I do want to say that I don’t think I was right to push myself so hard. If I had it to do over again I would accept help more often; maybe not for the hair-washing, but definitely for other tasks that I should have outsourced. I have learned from my experience.

November 21st, 2010 §

One of the most destructive emotions in my life is regret. Thankfully, I don’t have many decisions in my life that I would change if I had the chance. But there is one big medical one that I question daily: my decision to have my ovaries removed 18 months ago to put me into menopause and remove/significantly decrease some major hormones from being produced in my body.

In consultation with my oncologist, after chemotherapy was over I decided to take ovarian suppression injections. My period had come back within a few months of chemo ending even though I was in my late 30s. I was not going to have any more children. The tamoxifen I was taking had already started giving me ovarian cysts and I needed numerous ultrasounds to monitor them. Ovarian cancer was always in the back of my mind.

After one year of the injections (in which a thick needle is plunged under the skin of your belly and a small pellet of medication is placed which dissolves slowly over the course of one month) I decided I wasn’t going back; I couldn’t tolerate the questions every month with a menstrual cycle and hormone fluctuations. With my kind of breast cancer (estrogen and progesterone receptor positive), any remaning cancer cells in my body would be “fueled” by these hormones. I wanted to minimize them, and hopefully reduce my chance of cancer recurrence.

And so, after the year of injections I consulted with some surgeons. They felt that the ovary removal (oophorectomy) would be no harder on my body than the injections I’d already been taking. I had laparoscopic surgery in December of 2008 and felt good about the aggressive stance I was taking.

Then my world caved in. Within weeks of the surgery I was depressed. My hormones were bottoming out. Not just the estrogen and progesterone, but other ones the ovaries produce. I was plunged into menopause and all of its agony overnight. My hormone levels went not to the point of a menopausal woman (there are still some hormones present) but as my oncologist told me “of a prepubescent girl.”

I was depressed. I cried constantly. I was still getting over the surgery itself (not exactly the “walk in the park” that had been described to me) and had to miss the family Christmas vacation that year. Clarke and the 2 older kids went to Wyoming while I stayed with Tristan and tried to heal and regroup.

The joint pains started, the bone loss continued, the depression loomed. I had to watch my cholesterol numbers and must take osteoporosis medication after breaking ribs in a fall. I have sexual side effects that can’t be remedied with estrogen creams or pills. In the future I worry about the increased risks of dementia, heart disease and lung cancer without the protective benefits of estrogen.

But worse than any of them, the migraines began. I’d never had them before, but the overnight hormone drop brought them on fast and furious. Up to 15 a month.

It really is “always something.” Each decision is not isolated; everything I do to my body has ramifications and risks. I don’t know if I would have made the same decision if I knew what pain I was bringing on myself. All I know is that fear is a motivator. At the time all I could think about was the cancer. I felt that anything I could do to decrease the chance of my cancer recurring was worth it.

Some days I’m not so sure about that. I believe the doctors I consulted vastly underestimated the effect that this surgery can have. Perhaps as more women electively remove their ovaries if they test positive for the BRCA-1 and 2 genes we will learn more about the effect it has on our bodies (I have tested negative for both of those genes but it is a main reason women opt to have oophorectomies).

There’s no way to know if I made the right decision.

If my cancer stays in remission I will feel better about my decision. But as side effects mount and long-term health issues occur throughout my life because of this surgery and its repercussions, I can’t help but question if my fear may have pushed me too far.

October 15th, 2010 §

Part one: Tristan’s Valentine

My son Tristan is about to turn 4. I haven’t written about him much here. I started thinking about why that is, given that his life has given us more twists and turns than either of our other children. I think it’s precisely because he’s had his share of hardships that I have felt overprotective of him. But it really needn’t be that way.

Tristan’s physical problems are a bit unusual. For those of you who don’t know him, he had open heart surgery at seven months old to move an artery that was compressing his trachea, preventing him from breathing properly since the time he was born. He required feeding therapy to learn to eat after having trouble combining eating and breathing until that point.

He also had problems with his neck. From birth his head sat at an awkward angle. Doctors thought it was muscular torticollis that could be fixed with physical therapy. We did a DOC band to correct the flattened head he had as a result of this “fixed” neck position. But after a while my intuition told me it wasn’t muscular. I felt it was orthopedic, something that would be an extremely rare abnormality. I took him to an orthopedic surgeon who confirmed our fear: Tristan’s problems were more serious than just a tightened muscle.

We were told various diagnoses for his problems when he was about six months old– everything from cerebral palsy to Goldenhar Syndrome. But in the end, when pressed for a diagnosis they jokingly say he has “Tristan Adams Syndrome,” a combination of rare defects in his spine and hands.

The cervical vertebrae in his neck are not formed correctly. Half-formed, or fused together, the vertebrae near the base of his brain are mangled, appearing on x-rays, CT scans, and MRIs almost indistinguishable from one another. His adorable exterior hides a jigsaw puzzle-like appearance on the inside.

While the abnormal vertebrae caused him a severe head tilt to one side as an infant, it now appears from the outside as almost straight. As he’s grown his “z-curve” (two striking jogs in his neck which have thus far balanced eachother out; either one alone would have required surgical intervention already) has improved with growth.

We watch, we test, we monitor. If the congenital scoliosis (meaning a curvature of the spine since birth) worsens, he’ll need surgery to fuse his neck in a fixed state with rods and screws. His neck would not grow any more, and he’d have no mobility in it. Imagine having your neck in a position where it’s extremely short and you can’t turn it at all unless your whole upper body goes with it forever. So far, we’ve escaped this. But we are told that every growth spurt brings risk.

His other oddity are his hands. For the first year of his life we knew something was wrong, but no one could figure out what. He held his hands oddly. His thumbs just looked wrong– more like big toes. And finally, a hand surgeon was able to tell us: he has hypoplastic (underdeveloped) thumbs. He’s missing the muscle at the base of the thumb where the base of the thumb joins the wrist. I had never heard of that before. Likely, you haven’t either. That’s why no one could pick up on it. What does this mean? Functionally, it means his left thumb can’t bend at all. Try to pick something up holding your thumb out straight. Or hold a pencil, write your name. His right thumb bends slightly, but not “normally.” Oh, and yes, of course… he’s a lefty.

He doesn’t like to do things with his hands. He won’t write or draw. He can hold a spoon and fork, but prefers to eat with his hands.

Tristan’s surgeon says around now is a good time to do surgery to help get a bit more function in his left hand. By taking a tendon from another finger on his left hand and transplanting it to Tristan’s thumb, they hope to give him better mobility. It won’t allow him to bend his thumb. There isn’t a surgery that can do this: the muscle and tendon you use for this run all the way up to your elbow (who knew?!).

As I type this I know, looking at my thumbs while I type, that computers will be his saving grace. My thumbs stay straight when I type, and I am sure that he will learn quickly how to type and use a keyboard. He copies Paige and tries to play the piano. I think he might be able to do that too.

I remind myself about the documentaries I’ve seen over the years about people with different disabilities and how they’ve compensated. The YouTube video of the mom without arms who could change a diaper with her feet was one of the most amazing.

I know Tristan’s amazing spirit, his infectious giggle, his sweet and expressive face, his stubborn tenacity will get him through. I know he falls behind on every fine-motor skill evaluation. I know he won’t be able to play many sports well because of his hands or participate in lots of sports or fun activities because of the risk of neck injury.

When he brought home his valentines from school yesterday, his friend Bennett had written his name beautifully on the red paper. Tristan can’t write a letter. He knows them all, but he can’t write them.

My eyes teared up, jealous at the inscription.

I know he’s not going to do that anytime soon.

But I also know that somehow he will.

Someday he will.

And when he does,

that valentine with his name and mine

will go into my special box of keepsakes.

For always.

Shortly after that post, on his 4th birthday, Tristan had his tendon-transfer surgery.

…………………………………………………

Part two: It’s My Birthday and All I Got Was This Lousy Cast

My son Tristan had surgery yesterday. With no food starting at 8 PM the night before, and no drinking after 7 AM the morning of, Tristan was wheeled back to surgery at 3 in the afternoon. He asked only once for something to eat and drink. All day he played with Matchbox cars in his hospital bed waiting. Never a tear, never a complaint. A few times he gently asked, “Can we go home now?”

Surgery finished at 6 and was a success. Our fantastic and caring surgeon at Shriners Hospital, Dr. Scott Kozin, decided in the operating room after seeing the tendon in his ring finger that it wasn’t sufficient; he closed up that finger and used the middle finger instead. The tendon was transferred, the ligament stabilizing his thumb was tightened, the web space between his thumb and pointer deepened. All went well and a large cast was placed on his arm from fingers to shoulder.

Rather than a typical heavy fiberglass cast he received a more modern version of immobilization. To avoid having to “saw” the cast off in 3 weeks, this one will unwrap. For this reason, the pediatric patients are not as scared when the casts come off. These are not usable in every situation, but it was nice that he could benefit. Unfortunately, the worst part will be that there is a pin in his hand stabilizing his thumb right now. That will be pulled out when the cast comes off. I predict that removal is not going to go over too well.

When he woke up, Tristan’s first concerns were for water and his cars. Within an hour of awakening his personality re-emerged. As he started drinking and eating his spark returned. By 9:15 PM we were on the road, anxious to get him home. By midnight he was tucked in bed with a dose of pain meds and his stuffed animals.

The orange striped handmade pillowcase with dog pulltoys on it was a gift from the hospital as well as a cute quilted blanket with trucks on it. Every child gets a set of these handmade comforts.

A nurse found out it was his 4th birthday yesterday and rounded up some toys for him… cars and a book that makes fire engine sounds. He had a stash of toys to carry home from the hospital.

It wasn’t a great way to spend a birthday, but in the long run, it was a good sacrifice. There’s still some leftover cake for him to eat later today. The best present of all was having him come through surgery well and be able to come home with us without even having to spend the night. While there, we saw so many children with orthopedic injuries/issues that would keep them at Shriners for weeks or even months.

About 2 hours after the above picture was taken, Tristan looked like this:

That smile is the best present he could have given me.

……………………………………..

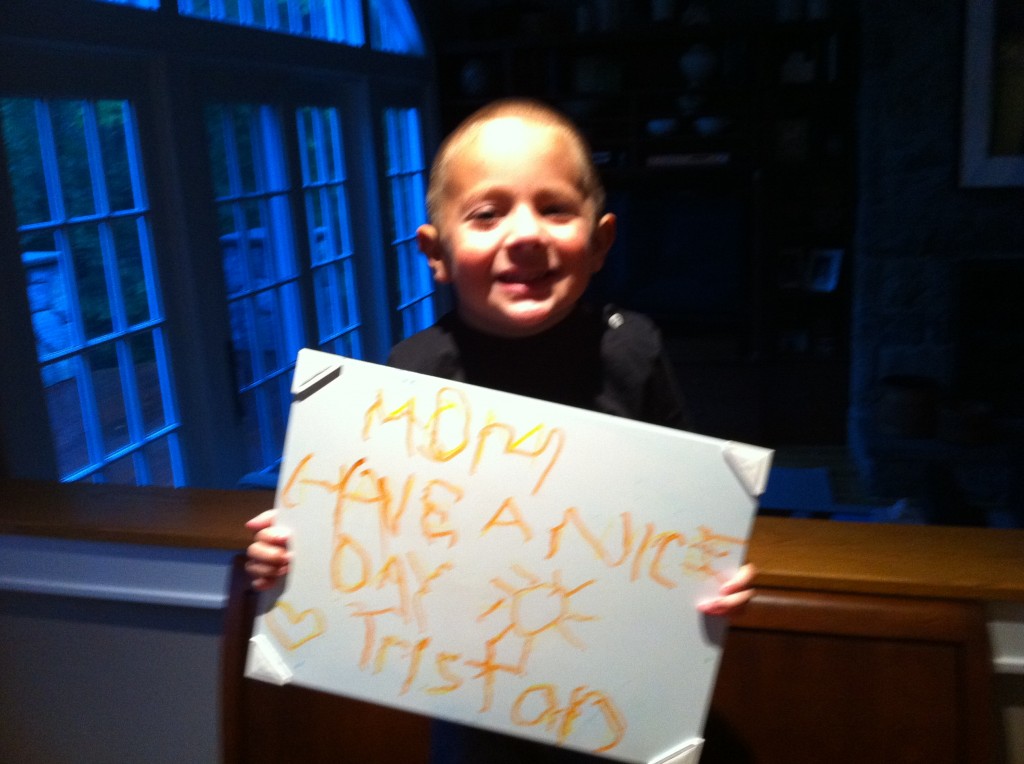

Part three: Have a Nice Day

Tristan recovered well from the surgery. I won’t show the picture of what his hand looked like when they removed the cast and there were black track marks of sutures all across his hand and wrist. The human body is amazing, healing itself after having so many things done to one tiny hand. Now, seven months later, all of the incisions in his hand are almost invisible, the only obvious one remaining is the long diagonal one on his left wrist where one end of the new tendon was attached. It’s still rather red but I know in time it will fade.

When the stitches came out Tristan needed extensive physical therapy to accomplish three tasks: stretch out the new web space, keep scar tissue from forming and tightening up the area, and get his brain used to communicating with the tendon in its new location.

A few months ago we encouraged him to hold a pen again, a paintbrush, any implement. If there’s one thing Tristan has always refused to do it’s written expression of any kind. The coordination and finger strength it takes to hold anything in his hand and make it do something deliberate is not an easy or enjoyable task for him.

About six weeks ago he started writing more. By “more” I mean completing a word without stopping. He had never colored a picture or fingerpainted. But through trial and error we patiently have worked with him to try a variety of options for writing. This week his therapist and I tried a dry-erase white board again. We’ve found that just because something doesn’t work once doesn’t mean it won’t work at a later date.

The combination of the marker making a smoother stroke (rather than the shaky, wavy lines he usually makes with pens, pencils, or crayons) and the smooth writing surface “clicked.”

The therapist was here at 6:45 a.m. on Tuesday morning for Tristan’s appointment. I took Colin to the bus and when I got back home and opened the door to the kitchen here is what I saw:

Now, to be fair, he did use his orange marker to trace the letters over the top of ones written in yellow by the therapist. It was a struggle, and took a lot of work. He still can’t write letters on his own without tracing. But it was a victory. It was a step. No mom could have been happier or prouder than I was. It might take him a little bit longer but he’ll get there.

And I will be there to hug him after every little step, the way I did when I saw this.

Tristan’s wish came true: I had a nice day.

In fact, I had a great day.

This week has been one of disappointment and adjustment. I met with the interventional radiologist on Wednesday afternoon to discuss what can be done for the metastases to my liver and what options are available. While chemotherapy has done a remarkable job in clearing up the cancer in my chest (it is resolved; if there, is small enough that it doesn’t show up on the scan), there are metastases to my liver that are chemotherapy-resistant. This means they have grown despite the fact that chemo that has worked well in other areas of my body.

This week has been one of disappointment and adjustment. I met with the interventional radiologist on Wednesday afternoon to discuss what can be done for the metastases to my liver and what options are available. While chemotherapy has done a remarkable job in clearing up the cancer in my chest (it is resolved; if there, is small enough that it doesn’t show up on the scan), there are metastases to my liver that are chemotherapy-resistant. This means they have grown despite the fact that chemo that has worked well in other areas of my body.

Link to Twitter

Link to Twitter