October 17th, 2014 §

My last post (“The Hardest Conversation”) showed you what a conversation with my teen daughter was like when we talked about my diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer in 2012. Today I wanted to share a conversation with my youngest child (now 8) that happened last year so you can see the variation in what their concerns were and how I dealt with each one.

As always, with cancer, age-appropriate explanations are important. Another vital piece of advice I’d like to share is that with all children, but especially young children, it is important to talk more than once about the topic. At the end of the first conversation I recommend asking young children, “Can you tell me what we talked about today?” to see if they have absorbed the most important pieces of information and that these pieces are correct. A day or two later it is always a good idea to ask, “Now that you’ve had time to think about our chat, do you have any questions?”

The following post was written in late 2013 on the eve of the surgery to put my medi-port in.

………………………………………………

“Why do you have to have surgery tomorrow?” seven year-old Tristan asks from the back seat after we drop off his 11 and 15 year old siblings this morning.

“Why do you have to have surgery tomorrow?” seven year-old Tristan asks from the back seat after we drop off his 11 and 15 year old siblings this morning.

“Because I need to have something put in my body called a port. It’s a little container made of something cool called titanium that lets the doctors put some of my medicines into my body in an easier way.”

“Can you see it?”

“Yes, you will be able to see that there is a lump under my skin, about the size of a quarter. But you will only see the lump. You won’t see the actual thing because that will be inside my body. You know how I have the scar on the front of my neck? It will be like that, here, off to the side, same size scar but with a bump under it.”

“Is it like the bubble I had on my neck when I was a baby?”

“Well, that was a skin tag, so that was a lot smaller. And they were taking that away. This is something they are putting in to help make it easier to get some of my medicines. And you know when you go with me and I have blood taken from my hand? Well now sometimes they will be able to just take it from there instead. So it helps with a few jobs.”

“Will you have it forever or do they take it out when your cancer goes away?”

(Driving the car, trying to keep tears in check, knowing this is a vitally important conversation. I’ve explained this to him before but I know it’s hard for him to understand.)

“Well, honey, remember I had cancer when you were a baby? Well, this time the cancer is different. A lot of the time you can have cancer and the medicines and surgeries make it go away and it stays away for a long, long time. Maybe even forever. Sometimes any cancer cells that might be left go to sleep and just stay that way. Sometimes you have bad luck and they wake up. Mine woke up after six years. And now the cancer cells are in places that I won’t be able to get rid of them all for good. I am always going to have cancer. This time my cancer is the kind that is always going to be here.”

“You’ll always need medicine. And the thing they are putting in?”

“Yes, honey, I will always need medicine for my cancer. And I will probably need to have the port in forever too.”

Long silence.

“I am glad you are asking me questions about it. I want you to always ask me anything. I will try to explain everything to you. I know it’s complicated. It’s complicated even for grownups to understand.”

Long silence.

“Mom, did you know people whose eyes can’t see use the ridges on the sides of coins to tell which one they are holding? So if you have a big coin with ridges that person would know it is a quarter?”

“That makes sense. How did you learn that?”

“At school. And so if it’s smooth you know it’s a nickel or penny. It’s important that they know what coin it is.”

“I think you’re right. That is very clever.”

( I stay quiet waiting to see where he will take the conversation next.)

“Remember when my ear tube fell out and was trapped in my ear and the doctor pulled it out and I got to see it? It was smaller than I thought it would be.”

“Yes, I thought the same thing.”

“I really wanted to see it. I wanted to see what it looked like.”

“Me too.”

“Can you show me a picture of it?”

“Of what?”

“The thing for tomorrow.”

“The port?”

“Yes. Or don’t you know what it will look like?”

“I know what it will look like. Sure, I will show you on the computer after school.”

“Okay.”

“It’s time for school but I am glad we talked about this. I want you to keep asking questions when you don’t understand something. I love you, Tristan. I hope you know how much. I know this is hard for all of us. I wish it were different. But we are going to keep helping each other. And talking about all of this is good. We can do that whenever you want.”

October 15th, 2014 §

From the time my oldest child, Paige, was born everyone kept telling me, “Just you wait.”

From the time my oldest child, Paige, was born everyone kept telling me, “Just you wait.”

When she made it through the terrible twos without much of a tantrum everyone kept telling me, “Just you wait.”

When she made it through elementary school and a move from NYC without trouble they kept saying, “Just you wait.”

“Just you wait,” they said, “girls are drama. You got lucky before. But the teen years? Oh boy… just you wait.”

Today she prepared me a bowl of soup and brought it up to my bedroom. I was resting after my surgery to remove malignant lymph nodes and tissue for testing yesterday, the room was dark. I invited her to come snuggle with me in the big bed. We’ve never let our children sleep in our bed so they think climbing in is a big treat.

I asked her if she wanted to talk about what was going on, about my news about having metastatic breast cancer. She did.

And so it began: an hour-long talk that started with her first question, “Are you scared?”

She asked questions about genetics and risks of getting cancer to what kind of treatments I might need.

She asked me again, as if to confirm for herself, “It’s not curable, right?”

We talked about my writing, about being public with my health status, about being open and honest with her and her brothers.

I told her that yes, I was scared. I explained that my fear usually comes from the unknown, in this case just how I will respond to treatments. I told her it was okay to be scared. That it’s normal, that sometimes fear makes you brave enough to do things you don’t think you can otherwise do.

I told her that I understood that sickness could be scary, that I didn’t want her to be afraid of me as I got sicker someday. “I would never be afraid of you, Mom. I’m only afraid of cancer,” she said. My heart squeezed and thrashed and the tears flowed.

We talked about her desire to be a doctor, a surgeon. She wanted to know what all of my surgeries and treatments had done. She wanted to know the difference between cancer “stage” and “grade.” We talked about the genetics of breast cancer and discussed the BRCA-1 and 2 genes (which I do not have). We talked about hormones and their role in puberty, menopause, and cancer. She wanted to know why outcomes are so variable. How will we know if treatments are working? I told her about the importance of her monitoring her own health, how hopefully we will have better screenings down the road.

I told her that for now I want her to live her life, for our house to be as normal as it can be for as long as it can be.

I told her she should try to focus on her schoolwork, her sports, and her friends. She told me that I was more important.

I told her that eventually I might need someone to help take care of me. “I will take care of you, Mom. You’ve always taken care of us,” she said.

We talked about her brothers, ages 11 and 6 and how she was going to have to help them. And her dad too. “I’m really good with hospitals and medical things, Mom… I’m just like you.”

She said she liked that I was open about it. That people knew. She thought it was best to be honest and appreciated the offers of support she’d received from friends and adults she knows.

I told her that what we were doing, lying there talking for an hour together about this, was the most important thing we could be doing today. I told her there wasn’t anything more important to me than my family. My job is to help them deal with this. Whatever this is.

I explained that what she needed from me would likely differ from what her brothers need; she is older and each of them would have different needs along the way. It’s my job to figure that out and address it. And my husband’s job now, too. How I take the lead on this will be important.

She asked if that was a lot of pressure, to have so many people reading my words, watching what I was doing. I told her it was. I told her it was my way of trying to help people. The same way that she wants to be a doctor to help others… well, I have always tried to see if I could help in my own way. And the way we talked before about the unknown being what’s scary? Well, my writing here means it’s less mysterious. Knowledge helps. Even if the knowledge is not what you want to hear, knowing is better.

Denial won’t change the course of things, and often makes things worse.

Secrecy is bad. Sharing and supporting are what I champion. And I know that de-mystification is a constant effort. I will continue to teach my children daily. I said I hoped that somewhere in all of this she could see how important science and medicine are in my world. And that if she does decide to be a doctor that is a noble effort. She will make me proud in whatever she does. As will my boys.

The funny thing is how much better I felt after we talked. The conversation was the hardest one I’ve had. The topics are gut-wrenching. But shining the light on them, on this disease, on what happens next, is the only way I know to cope, to help, to keep going.

We talked on and on as I combed my fingers through her long hair. I stroked her smooth, soft cheek. She was giving me strength.

And what I realized about people saying I should just wait because she’s going to eventually act out:

Waiting is a luxury.

Waiting means having time.

And that’s what I want most in this world right now.

August 22nd, 2014 §

Grow up faster,

Grow up faster,

Need me less,

Reach the sky,

Stand up tall.

Make time go,

Speed it up,

Get it done,

Don’t look back.

Hear my voice,

Feel my embrace,

Know I tried,

Look straight ahead.

Keep forging,

Thinking,

Feeling.

There is no choice,

This world is all there is,

Make it last.

Ours will be far shorter a time than it should be:

Years compressed into months, days, hours, minutes.

It will never be long enough,

It simply could never be enough time with you.

December 10th, 2012 §

I wake up in the middle of the night with a start:

Heart racing, breathing fast.

It was a dream, I soon realize. What I fear is not true.

The despair, the nightmare, the horror.

All of it was a creation of my mind.

In the dream I was searching for him.

He was gone.

He just disappeared.

My child jogged off into the woods, his identifiable gait

Seen from behind,

Tennis whites lit up the woods–

But where was his racquet?

I realize now in the dream he didn’t have it.

He ran off never to be seen again.

Did not get to his destination.

I searched. I could not find him.

I failed him.

I quickly erase the fiction from my mind,

It’s not true I tell myself:

It’s a dream.

Focus on something else.

It’s 12:56 AM.

My heart settles back to its rhythm

I hear the rain,

My children are safe in their beds.

I can relax now.

But ease does not come.

My fear is misplaced.

The nightmare still persists.

The reality is a different image.

There is a nightmare.

A waking one.

One that’s real and true, one I cannot shake off with time, or more sleep, or distraction.

My nightmare is loss, it is my children out of my grasp, it is separation.

I still fear all of those things.

But it is I who will wander off into the unknown

Leaving others behind

Waking in the middle of the night with only an image of me,

Fleeting,

As they search for me in vain.

I will be there, with them, but only in memories.

It will have to be enough.

But I know it won’t be.

After all,

This is what cancer nightmares are made of.

This is what grief does.

I cannot do more, be more, than I am right now.

But I can want more.

It is a parent’s prerogative.

I am greedy.

I make no apologies for wanting to see the things I want to see,

Wanting to share the things I want to share,

Wanting to live the life I want to live.

This is what I want.

This is what I hope.

This is what I dream.

October 5th, 2012 §

I loved the book The Age of Miracles by Karen Thompson Walker. I had the pleasure of meeting the author a few months ago. In the book, the earth’s rotation starts to slow. The days stretch longer with obvious consequences on daily life with some not-so-obvious effects on personal lives. I found the book immensely readable, creative, and thought-provoking (My teen daughter thoroughly enjoyed it too. It’s absolutely appropriate for that age group).

My own life has suddenly taken an opposite turn. It feels as if the world has sped up. The days are flying by. There just isn’t enough time.

It’s only been four days since we had an inkling from my oncologist that I had metastatic breast cancer, three days since I have known for sure. And now, in the middle of the night, it’s time I long for. The Earth is spinning so fast… how can it be I’ve been awake for two hours? Have I spent them wisely? What else could I be doing with those days, minutes, seconds?

I’ve done so much already.

I wanted to share a few ideas on things I’ve done already, many of them pertaining to my children. In the dizzying days after a metastatic cancer diagnosis there is so much emotion that it might be hard to think about what to do. You feel helpless. In some ways you are helpless until you get more information. But in the meantime here are some tips about what you can do.

I understand that not all of my readers have children. But for those of us who do, helping children adjust to this news is vital. It not only helps the children but can help relieve some associated stress for the parent.

- Don’t share your news until you know for sure what your particular diagnosis is. I don’t think you need to know your exact treatment; that takes time. But even knowing a general range of what might be used is helpful. If you have had cancer before, children will usually want to know if you will be doing the same thing (especially if it has to do with hair loss) or if it will be different.

- In my case I needed to have a mediastinoscopy with biopsy after my status was confirmed. It’s an outpatient surgery that inserts a camera through an incision in your neck to grab some lymph nodes for biopsy. I decided to focus on that concrete event mostly… it’s something children can wrap their heads around… Mom is going to the hospital (not uncommon in my household), having a small operation, will be back tomorrow night. I explained the cancer, the metastasis, and answered lots of questions, but I think the “one step at a time” was more easily tangible with the surgery as the immediate hurdle. If you will need an overnight stay for your particular surgery I think it’s best not to spring that news on children if possible. An overnight absence is best with a few days’ notice. Children, in my experience, are usually a bit clingy after bad news and that would provide the opportunity for follow-up questions and reassurance.

- Be sure you understand your diagnosis. Explain what words mean to children and to your friends. There are many misunderstandings about cancer and stage IV cancer. The word “terminal” might be scary. Stage IV cancer is not the same diagnosis in different diseases. Prognoses vary and some types of metastatic cancer can be slow-growing or respond well to treatment, allowing years of life.

- I think the phrase “it’s not curable but it is treatable” is important to teach and use.

- Wait to share your news publicly until after you have told your children (except with a few close friends you can trust to keep the information to themselves. This determination may not be as easy as it sounds). This also gives you a day or two to begin adjusting to the news so that when you do discuss it with your children you might have emotions a little more in check.

- As soon as you tell your children, be sure to tell adults who work with your children on a regular basis. If your children have learned the news, by the time they go to school, lessons, and sports, their teachers need to know. Email coaches, teachers, school administration, guidance counselors, school psychologists, and music teachers. Grief in children is complicated and it’s important that all of the adults know and can be on the lookout for odd behavior. Also, they need to be understanding if things don’t seem to be running as smoothly at home or a child seems tired or preoccupied. Two-way communication is key. Adults need to know they have the opportunity to bring any problems they see to your attention easily. Encourage them to do so, whether what they observe is positive or negative.

- Use counselors, especially school psychologists. My first call yesterday morning before I left for surgery was to reach the high school psychologist. Because Paige is in a new school (high school) I didn’t even know which person it would be. Even though it was only 9 in the morning when I called, the psychologist had already received my email (forwarded from the guidance department to the appropriate person) and had a plan in place to find my daughter during 2nd period study hall. She was able to introduce herself, talk to my daughter, and let her know how to get in touch with her as needed. They set up an appointment to meet to talk more in depth after their initial chat. Paige likes her, feels comfortable with her. This resource is invaluable. After my mother-in-law was killed in a car crash 3 years ago, the middle school guidance counselor became a refuge for Paige. When she was sad, distracted, needed a place to go have a good cry or talk, she had a safe place with an adult to help her. These individuals are part of my team. We are working together and it’s so important to use them.

- I have always felt that it’s important to be honest about a diagnosis; that is, open and public. I know this doesn’t work for everyone. The downsides of being public about a diagnosis are outweighed by the negative pressure for children if they have to keep a secret and bury feelings about such a serious topic. Children take their lead from you. If you are up front and comfortable discussing it, your children will learn to be that way, too.

- Call your other medical professionals and tell them of your diagnosis. Not only will they want to know because they care, but there may be instances where treatments may need to be examined or medications evaluated more often (for example, my endocrinologist wants to monitor my thyroid hormone levels more often than usual). They are all part of your team. They want to know. Many of the most touching and heartfelt phone calls I got were from my doctors this week. They cried with me, gave me information, offers of help, and caring. It also means if you have a situation when you need urgent medical care their office will already be aware of the situation and will likely respond more quickly to get you in to see the doctor.

- A carefully worded email is invaluable. Accurate information is documented so people don’t spread rumors. Friends can refer back to it if needed without asking you. They can forward it to other individuals easily, as can you. Choose your words carefully. The words you use will be repeated so make sure the email says what you want it to say to friends and relatives. The right explanation is much more helpful than a quick one sentence Facebook status update. People will have questions, and you can head many of them off by including that in your email (if you so desire).

I will be posting more tips about what I’m doing in the weeks and months ahead. Hopefully they will help you or someone you care about. There is so much you can’t control during this time, and that’s unnerving. Even taking steps like these can give you concrete tasks and a feeling of accomplishment that you are helping yourself and those you love.

December 2nd, 2011 §

I’m working on a new piece about grief during the holiday season, but really want to re-share this short post for those who missed it. I actually re-read it from time to time to remind myself of a valuable insight I had with two of our three children. This was originally written two days after their grandmother was killed in a car crash in 2009.

……………………………………………………..

Children are different.

From adults.

From each other.

I had to give two of my children different directives this morning:

One I told, “It’s okay to be sad.”

One I told, “It’s okay to be happy.”

I needed to tell my 7 year-old son that it was okay to cry, to be sad, to miss his grandmother.

I miss her too.

And it’s okay to let your emotions show.

It doesn’t make you a sissy or a wimp.

What it does make you is a loving grandson.

A grieving boy.

A bereaved family member.

But my ten year-old daughter needed a different kind of permission slip today.

I sensed she needed permission to smile.

To laugh.

To be happy.

I needed to tell her that it was okay to forget for a moment.

Or two.

To forget for a few moments that Grandma died.

It’s okay to still enjoy life.

The life we have.

Grandma would want that.

I told her that Grandma loved her so much.

And was so proud of the person that she is.

I reminded her how Grandma’s last phone call here last Sunday was specifically to tell Paige how proud she was of her for walking in a breast cancer fundraiser with me.

It’s okay to still feel happiness.

And joy.

It’s okay to let that break through the sadness.

Children are different.

But they take their cues from us.

I know my children.

I know that this morning what they needed from me was a sign that it was okay for them to feel a range of emotions.

It’s healthy.

Because what we are living right now is tragic.

And confusing.

And sad.

And infuriating.

If it is all of those things for me,

It can only be all of those things and more

To my children.

July 5th, 2011 §

I met a woman who told me something shocking.

It wasn’t that she’d had breast cancer.

Or had a double mastectomy with the TRAM flap procedure for reconstruction.

Or that she’d had chemotherapy.

What made my jaw literally drop open was her statement that she has never told the younger two of her four children that she’s had cancer.

Ever.

Not when she was diagnosed.

Or recovering from any of her surgeries.

Or undergoing chemotherapy.

She never told them.

To this day– five years later– they do not know.

I like to think I’m pretty open-minded. But I confess, it took a lot of self-control not to blurt out, “I think that is a big mistake.”

I’m a big believer in being open and honest with your children about having cancer. My caveat, using common sense, is that you should only give them age-appropriate information.

When I was diagnosed with breast cancer Tristan was six months old. Of course he didn’t understand what cancer was. Colin, age 5 at the time, understood some of what was happening. I explained to him what cancer meant, that I was going to need surgery to take the cancer out, where the cancer was, what chemo was, what it would do to my appearance and energy level. Using words like “I will be more tired than I usually am. I might feel sick to my stomach and need to rest more” explained things in words he could understand.

Age 8 and the oldest at the time, Paige understood the most when I was diagnosed. She had bigger questions and well as concerns about me (“Will I get it too? Who is going to take care of us? Are you going to be okay?”).

It’s not that I think small children always understand everything. But they are certainly able to sense that things are not “normal.” They can tell when people are acting strange. I think it’s important that they know there is a reason for that change. Children have a tendency to be egocentric; they think that everything is their fault. They may think they have done something wrong if everything at home feels different.

The woman told me she didn’t want to worry her children. She thought it “unnecessary” to tell them. She said when they got older she would explain it. I argue that by keeping her cancer a secret, she runs the risk of doing the opposite: making cancer seem scarier and more worrisome.

If children hear words like “cancer” casually in conversation as they grow up they will be comfortable with them; in that way, they won’t be frightened of them. If they understand the truth of the diagnosis and treatment they are dealing with reality. By hiding the truth, the unintended consequence is to make it seem worse than it is. By not telling children, and waiting until they are older, it reinforces the idea that cancer IS something “big and scary.” After all, if it weren’t, you would have told them already.

I think being secretive is a step backward to the days when cancer was only talked about in hushed tones: the “C” word or “a long illness.” These concepts might seem primitive to us now, but it wasn’t long ago that these vague labels were the norm. By showing our children, our friends, our neighbors, that we can live with cancer, live after cancer, we put cancer in its rightful place.

To me, the deception that goes on to lie to children about where you are going, what you are doing is lying about a fundamental part of your life. Cancer isn’t all I am — but it is a part. And it’s an important part of my medical history. If for the past 3 years I’d covered up where I was going and what I was doing, the web of deceit would have been extensive. I can’t (and won’t) live a life like that.

Further, I think it’s a poor example to set for my children.

Lying,

covering up information,

and omitting important information are all wrong.

With rare exception, the truth is always best.

Presented in the proper way,

commensurate with a child’s age,

a difficult situation can be not only tolerable but surmountable.

It takes work. It takes parents who can manage not only their own emotions about having cancer but also be involved with helping their children cope with it. It’s more work, but it’s worth it.

I think that woman made a mistake. I think her decision was harmful. I am sure she thinks she was doing her children a favor. I totally disagree. I think keeping this type of information from children “in their own best interest” is rarely– if ever– the right thing to do.

April 9, 2010

March 6th, 2011 §

Written September 18, 2009

Children are different.

From adults.

From each other.

I had to give two of my children different directives this morning:

One I told, “It’s okay to be sad.”

One I told, “It’s okay to be happy.”

I needed to tell my 7 year-old son that it was okay to cry, to be sad, to miss his grandmother.

I miss her too.

And it’s okay to let your emotions show.

It doesn’t make you a sissy or a wimp.

What it does make you is a loving grandson.

A grieving boy.

A bereaved family member.

But my ten year-old daughter needed a different kind of permission slip today.

I sensed she needed permission to smile.

To laugh.

To be happy.

I needed to tell her that it was okay to forget for a moment.

Or two.

To forget for a few moments that Grandma died.

It’s okay to still enjoy life.

The life we have.

Grandma would want that.

I told her that Grandma loved her so much.

And was so proud of the person that she is.

I reminded her how Grandma’s last phone call here last Sunday was specifically to tell Paige how proud she was of her for walking in the Komen Race for the Cure with me.

It’s okay to still feel happiness.

And joy.

It’s okay to let that break through the sadness.

Children are different.

But they take their cues from us.

I know my children.

I know that this morning what they needed from me was a sign that it was okay for them to feel a range of emotions.

It’s healthy.

Because what we are living right now is tragic.

And confusing.

And sad.

And infuriating.

If it is all of those things for me,

It can only be all of those things and more

To my children.

November 21st, 2010 §

The moments catch me off-guard,

like my brother used to do

when we were kids.

He’d lay in wait

around the corner

in the hallway upstairs,

behind the jog in the corridor

outside my bedroom.

He would leap out,

scaring me,

terrifying me,

and I would scream

and shake

and cry.

That’s what these moments do:

they make me

scream

and shake

and cry.

Last night it was Paige,

with her round angelic face,

eyes pink with tears bursting,

coming into the kitchen while I was on the phone with my parents.

“I went to the computer…

to send some email to some friends…

and all of the emails from her are there…

there’s just a whole list of emails from her there…

it just says ‘Barbara Adams’ the whole way down…

and I just keep thinking how she’s never going to write me back…”

And so we cried.

Together.

And we talked.

Together.

Tonight

I was cleaning the kitchen,

packing up backpacks,

doing things I thought were “safe.”

I thought I would be protected from

emotional assault.

I opened Colin’s green homework folder and

put in his math assignment.

A sheet was already inside the folder,

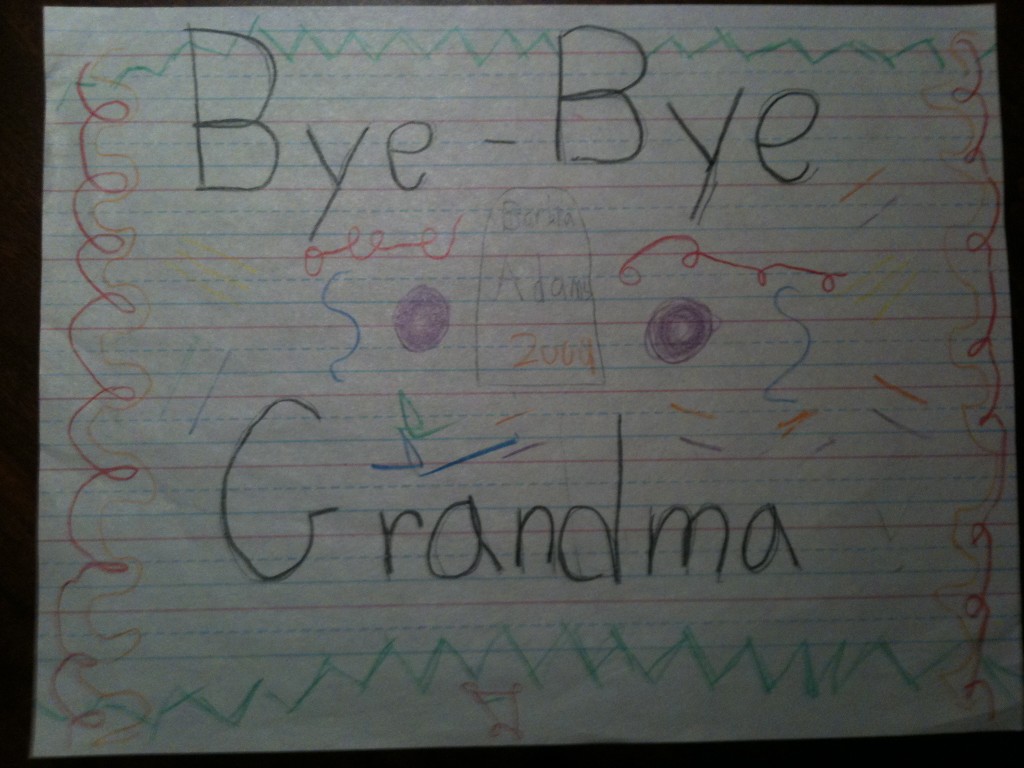

a red squiggly crayon line decorating one edge.

I pulled out the paper with reckless abandon,

expecting an innocent scribble,

a wasted silly drawing.

But instead, it was a piece of writing paper.

On it, neatly printed in his finest handwriting,

it said, “Bye-Bye Grandma”

and there was a tombstone shape in the middle

that said “Barbara Adams 2009.”

There were green zig zags on the top and bottom,

red squiggles on the left and right,

bright colors all around.

I wasn’t ready for it.

I didn’t know it was there,

in the shadows,

waiting,

lurking,

coiled to take advantage when I dropped my guard,

waiting for me to be vulnerable.

And so I acted just like I did when I was a

child and my brother scared me.

I screamed.

I shook.

And I cried.

I vowed not to let my guard down like that

Again.

I love you, Paige.

I love you, Colin.

I love that you loved your Grandma so much.

I loved her too.

I miss her too.

And my hurt may dull a bit,

but it’s never going to go away,

because some of my hurt is for you.

It hurts not only that I don’t have Grandma in my life,

but also that you don’t.

And that’s what makes me cry the most,

because I know how much she loved you both,

and little Tristan too.

One day

we’ll have to explain to him just how special she was

and how much she loved him

and all of the the special things she did to show it.

Thinking about the fact that she’s not going to be here to

show him for herself just breaks my heart…

It makes me want to

scream,

and shake,

and cry.

“Why do you have to have surgery tomorrow?” seven year-old Tristan asks from the back seat after we drop off his 11 and 15 year old siblings this morning.

“Why do you have to have surgery tomorrow?” seven year-old Tristan asks from the back seat after we drop off his 11 and 15 year old siblings this morning.

Link to Twitter

Link to Twitter