April 2nd, 2013 §

It’s been a wonderful but long few days. I was so run down yesterday that after our egg hunt I got into bed and pretty much didn’t get out for 9 hours. Tristan’s birthday was absolutely delightful. We held a birthday party, something he’s never had before. We’re not big on parties in our family; instead, we always have small family celebrations.

It’s been a wonderful but long few days. I was so run down yesterday that after our egg hunt I got into bed and pretty much didn’t get out for 9 hours. Tristan’s birthday was absolutely delightful. We held a birthday party, something he’s never had before. We’re not big on parties in our family; instead, we always have small family celebrations.

One year, Tristan was at Shriners Hospital for Children on his birthday having hand reconstruction surgery. When the surgeon you want has an opening in his schedule, you don’t say no because it’s your four year-old’s birthday.

When we’ve done parties it’s been my tradition to have a no-presents party. Our children get presents from us and close friends. Party guests, however, are not allowed to bring them (it’s fascinating to me how many people have a difficult time following this rule). Instead, they’re asked to bring the money they would have spent on a gift and donate it to charity (we designate Shriners Hospital for Children). Each party we’ve had in the past has raised at least $500. Paige has had two or three parties through the years, Colin has had two. In those particular years they got the party, cake, and presents from family members. This was more than enough.

We put a donation box out at the party and everyone can stuff the box. This year Paige wrapped and decorated the shoebox. The children who are bringing the donations also get a lesson in the joy of giving to others. Often the parents tell me that their children don’t understand why they can’t bring a present. That’s okay with me, I think it’s fine to force a discussion about giving to those in need. My children take pride in doing something good, and even when they are young and want to know why guests can’t bring gifts, I feel no guilt in explaining that not all children can afford to pay for the operations they need. When parents say to me, “Oh, I would love to do that but I don’t know how my child would respond,” I never quite understand that. It’s our jobs as parents to be role models, to show our children what’s important.

We put a donation box out at the party and everyone can stuff the box. This year Paige wrapped and decorated the shoebox. The children who are bringing the donations also get a lesson in the joy of giving to others. Often the parents tell me that their children don’t understand why they can’t bring a present. That’s okay with me, I think it’s fine to force a discussion about giving to those in need. My children take pride in doing something good, and even when they are young and want to know why guests can’t bring gifts, I feel no guilt in explaining that not all children can afford to pay for the operations they need. When parents say to me, “Oh, I would love to do that but I don’t know how my child would respond,” I never quite understand that. It’s our jobs as parents to be role models, to show our children what’s important.

When I had my own 40th birthday party a few years ago I did the same thing I have my children do: I asked guests to bring donations to charity in place of a gift. We must be willing to do ourselves what we ask of our children.

Shriners Hospitals provides care regardless of financial situation with an emphasis on orthopaedic care, spinal cord injuries, and burns. Tristan’s complex hand reconstruction helped him tremendously, he was able to have 3 procedures at the same time (a tendon transfer, a z-plasty to widen the web space, and a ligament tightening at the base of his thumb). Should he need cervical fusion surgery for the hemivertebrae and malformations in his neck that is where we will go (I’ve written elsewhere about Tristan’s congenital deformities in his spine and left hand). The team in Philadelphia including Dr. Randal Betz, Dr. Scott Kozin and physician’s assistant extraordinaire Janet Cerrone are very special to us.

Invitations and stickers from Easton Place Designs and the most adorable cookies from One Tough Cookie helped to make the day special. Tristan loved his karate party, and I love that I’ll be sending a big envelope to Shriners Hospital in Philadelphia from Tristan. I am so grateful to the families who helped to make this birthday so special for Tristan. I thank them on behalf of the children who will benefit from their generosity. Everyone does what’s right for them. This type of birthday celebration is what feels right to me.

Invitations and stickers from Easton Place Designs and the most adorable cookies from One Tough Cookie helped to make the day special. Tristan loved his karate party, and I love that I’ll be sending a big envelope to Shriners Hospital in Philadelphia from Tristan. I am so grateful to the families who helped to make this birthday so special for Tristan. I thank them on behalf of the children who will benefit from their generosity. Everyone does what’s right for them. This type of birthday celebration is what feels right to me.

…………………………………………………….

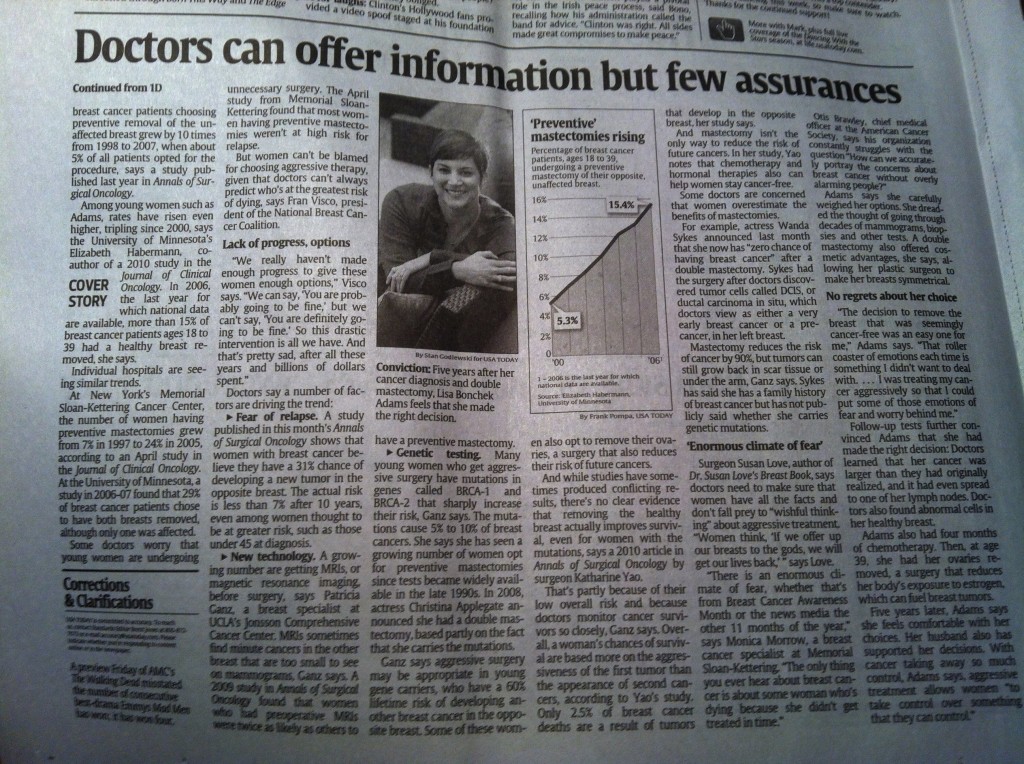

In case you missed it, Seth Mnookin had a great piece on Slate about the Time magazine cover about cancer. He and I had a great talk about this and I’m quoted briefly in the piece. You can read it here.

** Also, a reminder I’ll be on Doctor Radio (SiriusXM channel 81) this Wednesday, April 3rd at 1 PM EST on the Oncology Show. You can check the schedule here, and it does repeat a few times during the week. I am going to try to get an audio file for those of you interested in listening who won’t have access to it live. The topic? One of the most popular here on the blog: how to talk to people with cancer in a sensitive and caring way.

March 28th, 2013 §

Limboland is part of stage 4 cancer. On a daily basis I don’t know what’s happening inside my body. I often think about the cancer cells and wonder what they’re doing. Are they dying? Multiplying? It would be so nice to have a reliable blood test to easily and accurately measure how many of them there are at any given time. But these tests do not yet exist for us.

Limboland is part of stage 4 cancer. On a daily basis I don’t know what’s happening inside my body. I often think about the cancer cells and wonder what they’re doing. Are they dying? Multiplying? It would be so nice to have a reliable blood test to easily and accurately measure how many of them there are at any given time. But these tests do not yet exist for us.

My CA 15-3 test again showed a slight elevation from two weeks ago. The numbers have been bouncing around over the last few months (expected) with a slight upward trend (undesirable). It’s hard to know what this means. A few points here and there are not cause for alarm. This volatibility is inherent in this test (which is why some oncologists don’t do this test at all, and why it can’t be used as a screening device. Also, in some people the test doesn’t reflect changes in the amount of cancer present at all). So… it’s a bit to me like trying to juggle Jello.

Of course I want to walk in and have my number be lower than the previous time. But that’s not always possible. With the exception of my hands I’ve felt good for the last two weeks. I’ve been in a frenzy of activity this week with Tristan’s 7th birthday this weekend (more about that in the next few days) and lots of activities with the kids. How I feel is important; while blood tests can show how my counts are, lack of pain in new areas is good too. I received my monthly injection of Xgeva today as well.

I’m back at Sloan Kettering next week and Dr. Dang and I will huddle and strategize. Today my local oncologist and I talked about some ideas about how to treat this test result and what it potentially really means. Right now it seems we are in watchful waiting (not that there is anything new about that). As of today no repeat PET scan is scheduled. We will see if that decision changes next week. My prediction is we wait two more weeks to see where the levels are then and re-evaluate at that time.

Chemo starts this Sunday. I’ve been doing the maximum recommended dose for 5 days, and a slight decreased dose for 2 days. I think this time I’ll be pushing to the maximum dose for all 7 days. It’s hard to know what price I’ll pay for doing so, especially during a very busy week next week (Sloan appointment and then another gig on the Doctor Radio Oncology Show on Wednesday at 1 PM which I hope to attend in person). My hands are my biggest issue, this is just what happens with Hand/Foot Syndrome. I continue to treat my hands with all sorts of products and care, but the truth of the matter is that this is what Xeloda does when it is taken and leaches out of the capillaries. The only true remedy is a decreased dose or discontinuing it altogether. That’s not in the cards right now (thankfully).

It is always hard to hear news that’s not what you want. I’m sure some people would be filled with anxiety and upset after this type of news. I like to give myself a ten minute pity party and then get on with life. If I give myself up to worry and dread for the next two weeks, what have I accomplished besides ruining two precious weeks of my life? Instead I went to the grocery store and stocked my house with food for the long weekend. I came home and played with my new dog (sweet Lucy is especially lovable in times like this).

I am a role model: my children are watching how I handle all of this. Raising polite and kind children is not enough. My children’s mastery of resilience is as important as any other life skill I can teach them. If I become debilitated by anxiety, don’t pick myself up and press forward, I am teaching them a lesson they do not need.

It’s okay to be emotional or upset at bad news. Complete denial serves no one. Acknowledging emotions of anger, sadness and fear but still displaying strength, stamina and persistence is what I try to do.

I hate the turn my life has taken. I hate that this is what is happening to my family and to me. For now, though, I continue to focus on all of the things I can do, and am doing. I pour my heart out on this screen. Some people think I must be depressed all of the time if I have these dark emotions evident in my posts. I can assure you that this is not what I am like all the time. Those feelings exist, and are important. I wouldn’t be human if I didn’t have them. It’s important to get them out not only for my own well-being but also because I know many readers with cancer tell me I’m speaking for them.

So, it’s not what I wanted, but I’m not sounding the alarms. We watch, we wait, we treat. I consciously do the best I can every day. Some days I do better than others. Some days I have a short temper and take my anger at cancer out on my husband or my kids. I’m not perfect. I apologize to them. I tell them I’m trying my best but sometimes it just breaks through. They see that I am human too. I make mistakes.

I draw strength from you all every day. Thank you for your support.

March 19th, 2013 §

Alone.

Willing myself to recharge, gather strength, get ready, be stronger.

Chemo starts again.

One more week.

My relationship status with chemo on Facebook would read: It’s complicated.

Chemo keeps me alive.

Buys me time.

Gives me days, weeks, months.

But

Makes me sick.

Causes my hands and feet to numb, get tender, peel, redden, swell, ache, burn, throb.

Tires me, sickens me, weakens me.

How can I hate that which gives me hope?

I check in with friends on Twitter.

I see photos of beautiful people in watercolor places doing things I want to be doing.

I am jealous.

The light hits her hair so perfectly, magically, like a mermaid.

It makes me cry.

I literally weep at the beauty of a friend,

wishing I could be with her,

with them,

anywhere but here.

I had a dream of being at Sirenland.

I set a goal, but it has come and gone, unfulfilled.

I cannot decide if stage IV means I must downsize my dreams or shoot for the moon.

Is there nothing left to lose or simply nothing left?

It is late night in Positano now.

They have done their work for the day.

They have their late European dinner, their drinks, their views of the water shimmering at the base of the hill.

I was supposed to go on a trip there once, coincidentally.

A fifteen year anniversary present and celebration of finishing cancer surgeries and chemo six years ago.

Plans were made, everything was set.

Four days before planned departure, our (then) five year old son’s appendix ruptured.

Nine days of round the clock hospital bedside vigils followed.

No trip. No rebooking. No celebration.

But no regrets at being where our son needed us to be.

Wistful I remain.

Unsure I will see that place now.

I envy those who are there.

I wonder if they know.

How I envy them.

March 18th, 2013 §

Metastatic cancer is an introduction to topsy-turvy world.

Things I once counted down to now I must cheer.

The first time I was diagnosed with breast cancer (stage 2, in December of 2006), I counted my chemo treatments down. “Only 2 more adriamycin/cytoxans to go,” I might say, or “Only 4 Taxols left.”

Now I’m forced to be glad for the chemo rounds.

I started my 12th round of chemo yesterday, on Sunday the 17th. After being sick with a bad cold and stomach virus this week I’m feeling not-quite-ready to start again. I haven’t had enough time to rebound and my side effects are not as reduced as they traditionally have been. My feet and especially my hands are not in great shape and I’m limited as to things I can do. For a few days I had trouble walking. Some days I can’t hold a coffee mug. Most days buttoning and unbuttoning are a lengthy challenge. Typing is sometimes painful as well.

Whereas before I could look forward to the time when chemo would be over, now I must be happy for each round. I must realize that it means another week alive, another week the drugs are working.

Another week to be a wife, mother, friend, daughter.

Another week to write, another week to love.

Another week to hope there is a new treatment brewing.

My milestones used to be measured in how much time I had invested to get through to the other side: putting cancer in the back seat. The goal was successfully completing surgeries and chemo so cancer would be more like background noise rather than an attention-greedy headliner in the spotlight.

But now all of that is backwards. I don’t count down until my treatments are over because they are going to be here for the rest of my life. That’s a hard one to accept some days. There is no “when I’m done with treatment.” Not taking chemo would mean I’ve run out of options or the treatment is worse than the disease. There is no after. There is no “looking forward to being done.” Being done now only means death to me.

This is the way it is.

Everything is upside down.

And that’s how life has felt every day since I was diagnosed with Stage 4 breast cancer.

March 7th, 2013 §

Everything changes with a diagnosis of Stage 4 cancer. I don’t really think that’s an overstatement. My relationship with my oncologists has, by nature, changed as well. With stage 4 one of the things that’s especially important is good communication between physician and patient. It always is, but now two of the topics that are imperative to review at each meeting are side effects of medications/chemo and symptoms I’m having (especially pain).

Everything changes with a diagnosis of Stage 4 cancer. I don’t really think that’s an overstatement. My relationship with my oncologists has, by nature, changed as well. With stage 4 one of the things that’s especially important is good communication between physician and patient. It always is, but now two of the topics that are imperative to review at each meeting are side effects of medications/chemo and symptoms I’m having (especially pain).

I have always had two oncologists’ input on my treatment since my original diagnosis of stage II breast cancer in December of 2006. Even through the more than five years of remission, I continued meeting with them about my adjuvant therapy.

Immediately after I was diagnosed in October with stage IV my oncologists began talking about finding a balance between length of life and quality of life. These two aspects of my life would have to be constantly juggled. The art of medicine and its role in treating cancer suddenly has become crystal clear while the science of decision-making often remains blurred.

For many people it is often reassuring to hear there is a plan, a prescribed protocol. There is a type of comfort in being diagnosed with a disease and being told there are defined steps you need to take. With metastatic cancer it’s not crystal clear. Patients must often help decide what is right for them.

I was offered options about which treatment to try first: a traditional chemo or an anti-hormonal combination. One would attack cancer cells, but also attack the healthy cells in my body. The other would aim to “starve” the cancer of some of its fuel (hormones). One important positive feature about my cancer is that there are choices about how to try to keep it in check. This hopefully will equate to having stable disease for a while so I can live longer. Some types of cancer do not respond to certain therapies and therefore there are fewer options in treating them.

When I went to see my medical oncologist at Sloan Kettering, this week she pulled the chair over and sat only inches from me. I was on the exam table, in the modest red and peach Seersucker bathrobe Sloan uses for their exam gowns. We sat and talked about research and trials and side effects and my blog and my family. She gets emotional sometimes when we talk about the current situation. So do I.

Then Dr. Chau Dang said something that I will always remember. She said that many doctors start to distance themselves from their patients as the patients get sicker and closer to death. She said this is their coping mechanism. Of course I couldn’t help but wonder if the same process is what is behind some of my friends disappearing and rarely contacting me anymore. Some physicians, she said, seem to back away, needing emotional distance not to be weakened each and every time a patient dies.

In contrast, my doctor feels this is precisely the time in her relationship with her patients to embrace them, bring them close, provide them care and comfort as much as possible. It’s important to remember, she always says, that this isn’t a case, this is a life. A person with friends and families who love them. Death happens for all of us. It’s her role to do what she can to prolong life, and when that can’t be done anymore, it’s important to still care for the person, not just treat the disease.

The nature of the doctor-patient relationship changes over the course of illness. Perhaps nowhere is that truer than in oncology. I’ve always been a partner in my care, it’s the only way I know how to be. It’s my life, after all, and the decisions we make as a team are ones I do not want to regret because I gave up control or didn’t have adequate information. However, I also accept that treating cancer is not an exact science.

Some patients do not want to have options. They want their physician to pick the course of treatment that seems best matched for the patient and proceed. A patient sometimes doesn’t want choices; he or she wants the doctor to do the sifting and prescribing. This works for many people, and takes the responsibility off the patient. There is mental comfort in that approach, too. I can understand why some people make that choice.

One of the things that is difficult in being a true participant in your own care is that while you get the satisfaction of partial control, you also must accept responsibility if/when things go wrong. This is part of the deal.

Some things just are.

Some things just happen, even when you do all you can.

I have accepted this jagged truth all along.

But I think some people never do.

March 4th, 2013 §

Once or twice a week I awaken in the middle of the night with a poem in my head. I reach for my phone and I type frantically. I go back in the morning, or after a few days, and read what I’ve written. I know the words are important, streaming from my head like water breaking through a dam. This poem came from one of these middle-of-the-night sessions.

Once or twice a week I awaken in the middle of the night with a poem in my head. I reach for my phone and I type frantically. I go back in the morning, or after a few days, and read what I’ve written. I know the words are important, streaming from my head like water breaking through a dam. This poem came from one of these middle-of-the-night sessions.

If you let me

If you let me

I’ll cry you a river

Scream at the moon

Hold your hand

Kiss your mouth

Feel your heartbeat

Dream of more

Fear the end

Wish it were different

Pound my fists

Swear a blue streak.

If you let me

I’ll give you strength

Find a reason

Deliver some hope

Take a needle

Feel the pain.

If you let me

I’ll be grateful

Feign bravery

Take a stand

Do my best.

In the end

I’ll whimper softly

Try again

Give a last kiss

Take a last breath

Slip away.

February 21st, 2013 §

“I look so old in that picture.”

“I look so old in that picture.”

I hear this one a lot now that my friends and I are what they term “middle-aged.” They want to see and choose pictures before they get saved or shared; the confidence and carefree attitude in photos from our youth has slipped away.

It’s not just people my age, though. For example, my father in his 70s comments on how old he appears in photos I take, too. With a full head of white-gray hair, he doesn’t look old, I think… but even if he does? What’s wrong with looking his age? With plastic surgery and Hollywood showing altered appearances all the time it’s almost shocking when we see people who haven’t adjusted their appearance. Maggie Smith (most recently of Downton Abbey fame) has a face as wrinkled as a Shar-Pei, and we love her for it.

Aging isn’t easy. There are cruel sides: bodies that hurt, diseases like Alzheimer’s that strike mercilessly, loss of independence and body control. For sure, I don’t mean to imply that getting old is pleasant.

Aging is, however, the price one pays for living.

I look at getting old as a positive now. To age means to be alive. For some of us getting old is now a pipe dream. I will miss an entire generation of my life. That is the truth about my stage IV breast cancer.

I face the reality that I am not middle aged. I am living my own old age now, in my 40s.

February 11th, 2013 §

The finish line is the goal.

Runners strap on shoes, push their bodies, train for months.

Do it well. Do it faster. Faster than the others.

Laps around the track, tires squealing, pit stops along the way.

Checkerboad flags, shake the champagne.

Biking stages, climb the hills, pass the others, wear the gold jersey.

You got there first.

You won.

But I do not want the finish line.

I do not want to get there first.

I am dragging my feet.

Digging in my heels.

Fingertips grasping,

Losing touch,

Don’t make me go.

I’m fighting, crawling, resisting, doing everything I can.

Make the time slow down,

Make the days longer,

Make the end out of my sight.

I don’t want to be the first to the finish line.

I want to be last.

This time, losing would be winning.

January 31st, 2013 §

I always think these updates must be boring to read. I know they’re necessary, and important. I know this is how most of you get the nitty gritty details on my treatment. Somehow, though, I always wonder if they are actually educational or if they are too technical. So, that’s why I try to limit them to about once a week or when there are changes. My goal is to show you how these decisions get made (in my case only). Some cancers have very specific and formulaic treatment schedules. Metastatic disease often does not. It’s unclear which drug(s) will work and for how long. It’s never known how a patient will tolerate the drug initially and cumulatively as time goes on. The patient has a lot of leeway in many of these cases. There is no blueprint. A good team has communication about options and constantly revises their strategy.

I had this week “off” from chemo. The last few days I’ve felt very good. I have been spending lots of time with our new dog, Lucy, who has brought joy into our home in so many ways. We just adore her.

I was at Sloan Kettering last week and today I met with my local oncologist. Fortunately everyone in agreement after a review of all of the options. One of the things that’s always a concern is quality of life. My doctors are very keen on making sure I am comfortable and able to do things I enjoy. The balancing act of aggressive treatment to extend life without sacrificing too much quality of life is an integral part of treating metastatic cancer. There is no cure. But the goal is holding off the inevitable as long as possible.

I’ve had lingering trouble with the monthly IV bone drug Zometa. Some readers suggested I ask about the other available drug Xgeva, a subcutaneous injection also given once a month. They anecdotally reported fewer side effects. Both of my doctors do not believe Xgeva actually is better for my needs cancer-wise than Zometa, but also agree it’s not worse. One option was to try an IV steroid infusion of Decadron immediately prior to the Zometa to see if it helped with side effects. The other option was to try to the Xgeva and see if I had any side effects from that (most people report fewer to no problems with it, though most also do not have problems with Zometa after the first one or two times). I’ve opted to try the Xgeva. I would usually have gotten it today (28 day interval) but I have plans this weekend that are very important to me. I don’t want to risk being ill and having to cancel. It will not be a problem to get the injection on Monday, so I will postpone it for a few days. We’ll see how I tolerate the Xgeva shot and go from there.

My tumor marker number stayed relatively constant after that small increase two weeks ago. This is good, but leaves us in a bit of a quandary. We aren’t yet at the point of doing a repeat PET scan. The rise is not enough to warrant that, though we will do it soon. Neither is the increase enough to assume the chemo has stopped working after initially being responsive. We don’t know, as I said in the last update, if it’s an anomaly or a trend. The only things that can show us are more data points. I happen to like data points. I like seeing what happens every 2 weeks even if it means more of an emotional rollercoaster. We are only 4 months into this and I don’t feel that we have a handle on how I’m responding yet. Only time can shed light on that. I did have a good initial reaction to the drug which was encouraging.

So… since we’ve achieved a good decrease in the last 4 months with the Xeloda but now that is slowing down and I seem to have “bottomed out” on its efficacy, what now? We want to keep everything where it is. If we can get more of a decrease, that’s the best. If not, we need it to hold steady. We all agree it’s time to try again to increase the chemotherapy dose and see if I can both tolerate it and get a stronger marker response. I started at 8 pills a day in the beginning (for about 2 months) and had to decrease about two months ago to 7 pills a day when side effects became intolerable.

It’s time to walk into the fire again. There is no manual for how to do this. We all brainstorm, we talk about what my goals are, we talk about what makes scientific sense. The idea this time is to increase, but not go back to the 8 pills for the whole round. Instead, to try to get more chemo in my system, I will alternate 7 and 8 pills for the week. We’ll see how I do. Debilitating nausea, stomach pain, hand/foot syndrome, and migraines have been my issues with this drug in the last month.

Also, I will change my start day. Thursday night was my usual. Lately, however, I’ve felt rotten on the weekends (both weekends this time around, as effects often last into day 10 or 11 which technically are “off” days for me). I will now start chemo on Saturday night or Sunday morning and see if we can shift my “rotten days” to weekdays instead. I want more quality days with my family on weekends if I can get it.

This is all educated guesswork, a constant dance of drugs and schedules and side effects and efficacy.

There is no manual.

There is no “must.”

There is only me, floating away, trying to grasp the fingertips of treatment and hope.

January 19th, 2013 §

I wrote this back in 2010. Just like in this week’s “I think so too” I decided to think about the history of an object.

………………………………..

I took my friend Brenda out to lunch for her birthday today. While we were sharing an appetizer, a group of four people entered the restaurant: three men dressed in business attire accompanied a woman with a knit cap on. I realized in an instant she was bald underneath that covering and postulated that the hat would not be coming off.

They took off their coats and sat down at the table. I watched them for a while, from a distance, across the restaurant. Indeed, the hat did not come off. She was bald, most certainly, and likely undergoing chemotherapy. My mind started to wander, and I started to wonder. Was she at a business lunch and able to keep working during this crisis? Was she done with treatment and waiting for her hair to grow back in or was she on an “off week” of chemo when food might be somewhat appealing?

I kept looking at her hat. It was freezing cold out today, so it wasn’t particularly out of place. But I kept staring at it. It looked handknit. Had someone she knew made it for her? Had she gotten it from the basket at the cancer center where people knit and donate hats for patients?

I wonder what she’ll do with the hat when her hair grows back in: will she throw it away? Burn it? Give it to someone else who needs it? After wearing those head coverings day after day, you don’t want to lay eyes on them again. After my hair grew back, I saved my scarves for a friend’s sister who was set to start chemo shortly after I finished. I recently saw pictures of her wearing them. It’s odd to see them, associated with so many memories for me, on her head too. Now I have the scarves back, and some have already been lent to another member of the club.

My wig, worn twice, is packed away in the basement. I will soon donate it to a charity that provides wigs to women who can’t afford them. I hate that wig. I hate what it looks like. I hate how it feels. I hate how I looked in it. Twice I wore it, and I had to keep from tearing it off every second it was on my head. It wasn’t me; I felt like someone else in it. But I just can’t get rid of it yet. It’s like a trophy for walking through the fire.

I wonder if that woman I saw at lunch today feels like that. She and her group finished their meals and left before I did. I was really sorry I didn’t get to tell her that her hat looked great on her.

January 17th, 2013 §

There is comfort in routine. Some people are superstitious. Sometimes they want the same chemo nurse, the same appointment time, the same chair. “If it’s working don’t mess with it” applies to many things about treating cancer.

I’m always thinking about continuity and the stories that objects tell. I’ve written twice about the tape measure my plastic surgeon used to measure me before surgery. I’ll post those pieces again this month. Whenever I sit in a chair in a doctor’s office I think about all of the people who have sat in it before me.

Each person has a story. So, too, does each chair. Here is one from 2011.

……………………………

Back in 2011 my plastic/reconstructive surgeon asked, “Did you know it’s been four years since your reconstruction surgery?”

Immediately he chuckled, “Of course you know that,” he said, realizing my mental calendar was certainly more precise than his– of course I marked the days off in my head.

Whenever I sit in a waiting room I am instantly transported to that place and time. I sit and watch patients walking in and walking out. I can tell by hearing what the time interval until their next appointment what stage of treatment they are in.

I sit in the chair, the same one I did four years ago.

It’s the same chair, but I am not the same person.

My body is not the same.

There is continuity in that chair.

There is a story it tells me.

I wrote this piece to the next person who sits in that chair.

………………………….

That chair you’re sitting in?

I’ve sat in it too.

In waiting rooms. Chemo rooms. Prep rooms. For tests. Surgeries. Procedures. Inpatient. Outpatient. Emergency visits. Routine visits. Urgent visits. To see generalists. Specialists. Surgeons. Alone. With friends. With family members. As a new patient. Established patient. Good news. Bad news. I’ve left with new scars. Prescriptions. Appointments. Words of wisdom. Theories. Guesses. Opinions. Statistics. Charts. Plans. Tests. Words of assurance. More bloodwork. Nothing new. Nothing gained. Nothing but a bill.

That feeling you’re having?

I’ve had it too.

Shock. Disbelief. Denial. Grief. Anger. Frustration. Numbness. Sadness. Resignation. Confusion. Consternation. Curiosity. Determination. Dread. Anxiety. Guilt. Regret. Loss. Pain. Emptiness. Embarrassment. Shame. Loneliness.

That day you’re dreading?

I’ve dreaded it too.

The first time you speak the words, “I have cancer.” The first time you hear “Mommy has cancer.” The day you wear a pink shirt instead of a white shirt. Anniversary day. Chemo day. Surgery day. PET scan day. Decision day. Baldness day. The day the options run out.

Those reactions you’re getting?

I’ve had them too.

Stares. Questions. Pity. Blank looks. Insensitivity. Jaw-dropping comments. Tears. Avoidance.

Those side effects you dread?

I’ve dreaded them too.

Nausea. Vomiting. Pain. Broken bones. Weakened heart. Baldness. Hair loss. Everywhere. Unrelenting runny nose. Fatigue. Depression. Hot flashes. Insomnia. Night sweats. Migraines. Loss of appetite. Loss of libido. Loss of breasts. Phantom pain. Infection. Fluid accumulation. Bone pain. Neuropathy. Numbness. Joint pain. Taste changes. Weight gain. Weight loss.

That embarrassment you’re feeling?

I’ve felt it too.

Buying a swimsuit. Getting a tight-fitting shirt stuck on my body in the dressing room. Having a child say “You don’t have any eyebrows, do you?” Asking the grocery line folks to “make the bags light, please.” Wearing a scarf. Day after day. Wondering about wearing a wig because it’s windy outside and it might not stay on.

That fear you’re suppressing?

I’ve squelched it too.

Will this kill me? How bad is chemo going to be? How am I going to manage 3 kids and get through it? Will my cancer come back and take me away from my life? Will it make the quality of life I have left so bad I won’t want to be here anymore? Is this pain in my back a recurrence? Do I need to call a doctor? If it comes back would I do any more chemo or is this as much fight as I’ve got in me? What is worse: the disease or the treatment?

That day you’re yearning for?

I’ve celebrated it too.

“Your counts are good” day. “Your x-ray is clear” day. “Now you can go longer between appointments” day. “See you in a year”day. First-sign-of-hair day. First-day-without-covering-your-head day. First taste of food day. First Monday chemo-isn’t-in-the-calendar day. Expanders-out, implants-in day. First walk-without-being-tired day. First game-of-catch-with-the-kids day. First day out for lunch with friends day. First haircut day. “Hey, I went a whole day without thinking about cancer” day. “Someone asked me how I’m doing, I said ‘fine’ and I meant it” day.

That hope you have?

I have it too:

Targeted treatments. Effective treatments.

Ultimately, someday, perhaps: a cure.

Don’t you think that would be amazing?

I think so too.

January 13th, 2013 §

Originally written on January 30, 2009 (the two year anniversary of my surgery).

……………………………..

I had two surgeons that day:

one just wasn’t enough for the job.

The surgical oncologist would take away,

the reconstructive surgeon would begin to put back.

Before I headed off into my slumber,

I stood as one marked me with purple marker.

He drew,

he checked,

he measured.

And then a laugh,

always a laugh to break the tension:

Surgeons must initial the body part to be removed to ensure

they remove the correct one.

But what if you are removing both?

How silly to sign twice,

we agreed.

And yet he did,

initialing my breasts with his unwelcome autograph.

The edges of the yellow fabric measuring tape he used

had purple fingerprints up and down their sides;

use after use had changed their hue.

And now it was my turn to go under the knife –

a few more purple prints on the tape.

I got marked many a time by him that year.

Endless rounds of

purple dots,

dashes,

and lines

punctuating my body

with their strange, secret blueprint

only those wearing blue understood.

We stood in front of mirrors

making decisions in tandem

as to how my body should and would take new shape.

Two years today and counting.

Moving forward.

Sometimes crawling,

sometimes marching,

and sometimes just stopping to rest

and take note of my location.

Numb inside and out,

but determined.

Grateful,

hopeful,

often melancholy.

Here comes another year

to put more distance

between

it and me.

Let’s go.

January 12th, 2013 §

Now that my cancer is stage IV many things that once seemed important are now at the bottom of my list. I distinctly remember during and after my breast reconstruction that I was very obsessed with every tiny detail about my implants. What size should they be? Were they healing well? Were they even? How did they compare to other women’s reconstructed breasts?

I think after I finished chemo I needed something to focus on. It seemed that this was something positive. Something for me. Something that would make me feel better (after all, those tissue expanders before the implants were the pits).

The time between when I was diagnosed and when I had my double mastectomy was about one month. Those were anxiety-filled weeks. Though I consoled myself with the news that my cancer was confined and surgery would most likely be enough to treat it, later I learned after the mastectomies that my cancer was actually stage II.

I look now at this piece I wrote and I can still connect to it. I still remember what it felt like. But now that I’ve got metastatic cancer I don’t give a damn about how my implants look. None of that matters to me. One of my first phone calls after the new stage IV diagnosis was to my plastic surgeon to ask if there was any reason to consider removing them if it would help any of my treatments that are to come (there isn’t).

This piece was written about my first diagnosis and surgery… when it was all very new. It seems so long ago. A lifetime. It’s been six years.

……………………………………

In the weeks before my surgery, I looked at pictures of double mastectomy patients on the Internet. I Googled “bilateral mastectomy images before and after” thinking I was doing research. I thought I was preparing myself for what was coming.

In reality I was trying to scare myself. I wanted to see if I could handle the worst; if I could, I would be ready. My reaction to those images would be my litmus test.

Some of the pictures were horrific. I sat transfixed. I looked. I sobbed. I saw scarred, bizarre, transformed bodies and couldn’t believe that was going to be my body.

Days later, when I met my surgeon for my pre-op appointment for the first time he said, “From now on, don’t look at pictures on the Internet. If you want to see before and after pictures, ask me: look at ones in my office. You can’t look at random pictures and think that’s necessarily what you are going to look like.”

All I could do was duck my head in an admission of guilt. How did he know what I’d done?

I realized how he knew: other women must do this. Other women must have made this mistake.

The aftermath is terrible to me though not in the ways I’d anticipated. I have no sensation in my chest. I never will.

A major erogenous zone has been completely taken away from me. Yes, I have new nipples constructed, but they have no feeling in them; they are completely cosmetic. The entire reconstruction looks great but I can’t feel any of it. It does help me psychologically beyond measure to have had these procedures though.

Here I sit, two gel-filled silicone shells inside my body simulating the biologically feminine body parts I should have. And sometimes that thought is disturbing.

To be clear: I don’t regret having them put in. I’ve never regretted that. It was a decision I made, and made deliberately. I knew that reconstructing my breasts was the right decision for me. I am overwhelmingly happy with the cosmetic appearance and the wonderful job my talented surgeon did. I will always be grateful to him for what he’s done.

I definitely don’t remember what my breasts looked like before. I only remember these.

I once asked my plastic surgeon to see my “before” pictures a year or two after my reconstruction was over. You know what? My “before” breasts didn’t look so great.

In my mind they did though.

In my mind, everything about my life before cancer was better.

But that’s not the truth.

Don’t take that as an endorsement of the “cancer is a gift” nonsense though.

My mind distorts the memory of my body before cancer. Then forgets it.

My mind distorts the memory of my life before cancer. Then forgets it.

With time, I can get used to a new self.

It’s like catching my reflection in the mirror: only lately do I recognize the person staring back at me.

For over a year the new hair threw me. It’s darker than I remember it being before it fell out. It’s shorter than it was before, too.

And the look in my eyes? That’s different also.

I just don’t recognize myself some days.

Sounds like a cliché if you haven’t lived it.

But it’s true.

January 9th, 2013 §

Elizabeth Edwards reached many people because she was in the public eye, but inspirational people also live quiet lives. We can be inspired by Edwards’s grace and courage as she dealt with the challenging parts of her life in the same way we can find inspirational people around us each and every day. These are all people we can connect with and learn from. In doing so, we better ourselves.

When she was diagnosed with metastatic cancer people told me not to worry: it wouldn’t happen to me just because it happened to her. That’s true. It wouldn’t happen just because it happened to her. But it did happen. And now I look back on everything I’ve said for the past 5.5 years and I am glad I expressed those thoughts as they were happening. Because my fear came true.

…………………………………..

(from December 7, 2010).

I didn’t know Elizabeth Edwards. In fact, I wrote a piece critical of her when she initially stood by John after his affair. I was disappointed when she gave an interview on CNN in May of 2009 and spoke only of John’s “imperfection” rather than calling him the cheater he was and kicking him to the curb. I was angry she hadn’t used her interview time to talk about herself, her cancer, her life: the topics I wanted to hear about. I was angry at her for not claiming her remaining years of life as her own.

So why am I sitting with tears in my eyes because she has died?

I cry because it makes me feel vulnerable and scared of what this disease can do to me: what it did to her.

Yes, I know… there are plenty of men and women who get cancer, have treatment, and stay in remission for the rest of their lives. And, in essence, isn’t that what every cancer patient hopes for, as Betty Rollins wrote, “to die of something else”?

I don’t think it makes me pessimistic, depressing, or negative to think that I am vulnerable.

It’s the truth. It’s my truth.

Anyone who hasn’t been to the oncologist with me to see my risk-of-recurrence charts, my mortality charts, my decision-making discussions along the way can’t say to me “Oh, don’t worry, that won’t be you.” No one, including me, knows how it will go.

People tell me: stay strong, just think positive, you can’t generalize from her situation.

I respond: I am strong, I hope for the best. I don’t think positive thinking is going to save me if there are remaining cancer cells still in me.

I hope that people won’t say to someone who has been diagnosed with cancer, “Don’t worry, what happened to Elizabeth Edwards won’t happen to you.” Because while we do everything we can to ensure we die of something else, it just isn’t always the case. In 2006 her oncologist told her that there were many things going on in her life, “but cancer was not one of them.” Things change quickly, cancer can recur when you least expect it.

I have sympathy for her family. I cry for her children. I am saddened about the years she spent with a man who didn’t deserve her. I am angry about the time she wasted on him. I hoped she would be an example of someone who would keep cancer at bay.

I grieve for that hope, now gone.

January 7th, 2013 §

Revisiting old blogposts is taking me on an emotional rollercoaster. Being on the other side — having things I was most afraid of actually coming true — gives the pieces a whole new meaning. Of course one of my main fears was that my cancer would return. Of course, it has, and worse. The metastases I have now are exactly what I feared most after my treatment was complete the first time around.

Again, I’d like to say that even when I feared it, as I would think most people who have had cancer do have fear of cancer returning/metastasizing, hearing the words “You have Stage IV cancer” bears no relationship whatsoever to the fear you have when it’s a hypothetical. The anxiety, the panic, the worry… all of those were only a fraction of what it felt like to be told it was actually true. This is what my life will be.

As I re-read the post below I got emotional. The words I wrote here over two years ago are still so true for me. This post captures my fervent wish to document my thoughts and feelings for my children. I still feel a strong desire to be understood. Perhaps some of this is because I think in many cases people with cancer do not feel understood.

Katie and I became friends after I read her book. Great friends. We talk about Suzy. We talk about french fries and silly socks and Pilates. We talk about her work and we talk about our kids. We talk about cancer. We talk about the most frivolous parts of life and the most serious. As I write below, “Even after her death, Suzy has the lovely ability to inspire, to entertain, to be present.” In life, so does her daughter, Katie.

………………………………….

There comes a point in your life when you realize that your parents are people too. Not just chaffeurs, laundresses, baseball-catchers, etc.– but people. And when that happens, it is a lightbulb moment, a moment in which a parent’s humanity, flaws, and individuality come into focus.

If you are lucky, like I am, you get a window into that world via an adult relationship with your parents. In this domain you start to learn more about them; you see them through the eyes of their friends, their employer, their spouse, and their other children.

Yesterday I sat transfixed reading Katherine Rosman’s book If You Knew Suzy: A Mother, A Daughter, A Reporter’s Notebook cover to cover. The book arrived at noon and at 11:00 last night I shut the back cover and went to sleep. But by the middle of the night I was up again, thinking about it.

I had read an excerpt of the book in a magazine and had already been following Katie on Twitter. I knew this was going to be a powerful book for me, and I was right. Katie is a columnist for The Wall Street Journal and went on a mission to learn about her mother after her mother died in June, 2005 from lung cancer. In an attempt to assemble a completed puzzle of who her mother was, Katie travels around the country to talk with those who knew her mother: a golf caddy, some of her Pilates students, her doctors, and even people who interacted with Suzy via Ebay when she started buying up decorative glass after her diagnosis.

Katie learns a lot about her mother; she is able to round out the picture of who her mother was as a friend, a wife, a mother, a strong and humorous woman with an intense, fighting spirit. These revelations sit amidst the narrative of Katie’s experience watching her mother going through treatment in both Arizona and New York, ultimately dying at home one night while Katie and some family members are asleep in another room.

I teared up many times during my afternoon getting to know not only Suzy, but also Katie and her sister Lizzie. There were so many parts of the book that affected me. The main themes that really had the mental gears going were those of fear, regret, control, and wonder.

I fear that what happened to Suzy will happen to me:

My cancer will return.

I will have to leave the ones I love.

I will go “unknown.”

My children and my spouse will have to care for me.

My needs will impinge on their worlds.

The day-to-day caretaking will overshadow my life, and who I was.

I will die before I have done all that I want to do, see all that I want to see.

As I read the book I realized the tribute Katie has created to her mother. As a mother of three children myself, I am so sad that Suzy did not live to see this accomplishment (of course, it was Suzy’s death that spurred the project, so it is an inherent Catch-22). Suzy loved to brag about Katie’s accomplishments; I can only imagine if she could have walked around her daily life bragging that her daughter had written a book about her… and a loving one at that.

Rosman has not been without critics as she went on this fact-finding mission in true reporter-style. One dinner party guest she talked with said, ” … you really have no way of knowing what, if anything, any of your discoveries signify.” True: I wondered as others have, where Suzy’s dearest friends were… but where is the mystery in that? To me, Rosman’s book is “significant” (in the words of the guest) because it shows how it is often those with whom we are only tangentially connected, those with whom we may have a unidimensional relationship (a golf caddy, an Ebay seller, a Pilates student) may be the ones we confide in the most. For example, while Katie was researching, she found that her mother had talked with relative strangers about her fear of dying, but rarely (if ever) had extended conversations about the topic with her own children.

It’s precisely the fact that some people find it easier to tell the stranger next to them on the airplane things that they conceal from their own family that makes Katie’s story so accessible. What do her discoveries signify? For me it was less about the details Katie learned about her mother. For me, the story of her mother’s death, the process of dying, the resilient spirit that refuses to give in, the ways in which our health care system and doctors think about and react to patients’ physical and emotional needs– all of these are significant. The things left unsaid as a woman dies of cancer, the people she leaves behind who mourn her loss, the way one person can affect the lives of others in a unique way… these are things that are “significant.”

I woke up in the middle of the night thinking about the book. My head spun with all of the emotions it raised in me. I think that part of the reason writing has become so important to me is precisely because I do realize that cancer can return at any moment. And if you don’t have an author in the family who might undertake an enormous project as Katie did, where will that explanation of who you were — what you thought — come from?

Is my writing an extension of my desire to control things when cancer has taken away so much of this ability?

Is part of the reason I write an attempt to document my thoughts, my perspective for after I am gone… am I, in a smaller way, trying to do for myself what Katie did for her mother?

If I don’t do it, who will do it for me?

And in my odd way of thinking, am I trying to save anyone the considerable effort of having to work to figure out who I was– deep down?

My blog originally had the title “You’d Never Know”: I am telling you things about myself, my worldview, and my life, that you would otherwise have no knowledge of. One of the things people say to me all the time is, “You’d never know to look at you that you had cancer.” After hearing this comment repeatedly I realized that much of our lives are like that:

If we don’t tell someone — share our feelings and experiences — are our lives the proverbial trees falling (unheard) in the forest?

What if you die without being truly understood?

Would that be a life wasted?

If you don’t say things for yourself can you count on others to express them for you?

Further, can anyone really know anyone else in her entirety?

After a loved one dies, there always seems to be at least one mystery person: an individual contacts the family by email, phone, or in person to say, “I knew your loved one: this is how I knew her, this is what I remember about her, and this is what she meant to me.” I know that this happened when Barbara (my beloved mother-in-law) died suddenly in a 2009 car crash. There are stories to be told, memories to be shared. The living gain knowledge about their loved one. Most often, I think families find these insights comforting and informative.

Katie did the work: she’s made a tribute to her mother that will endure not only in its documentation of the person her mother was (and she was quite a character!) but also in sharing her with all of us.

Even after her death, Suzy has the lovely ability to inspire, to entertain, to be present.

I could talk more about the book, Katie’s wonderful writing, and cancer, but I would rather you read it for yourself. I’m still processing it all, making sense of this disease and how it affects families, and being sad that Katie’s children didn’t get to know their grandmother. Katie did have the joy of telling her mother she was pregnant with her first child, but Suzy did not live long enough to see her grandson born. In a heartwarming gesture, Katie names her son Ariel, derived from Suzy’s Hebrew name Ariella Chaya.

I thank Katie for sharing her mother with me, with us. As a writer I learned a lot from reading this book. I’ve said many times recently that “we don’t need another memoir.” I was so wrong. That’s like saying, “I don’t need to meet anyone new. I don’t need another friend.” Truth is, there are many special people. Katie and Suzy Rosman are two of them.

December 20th, 2012 §

Today marks the six year anniversary of the day I was first told I had breast cancer. When the radiologist told me the news, she also said she didn’t know exactly what it was or how bad it was.

This is why you do not schedule mammograms or biopsies right before a holiday. Especially Christmas. You’ll be going on vacation… and if you aren’t going on vacation, the doctors, nurses, and pathologists will.

I was told on December 20, 2006 that I almost certainly had cancer based on the mammogram and ultrasound images. I’d need a biopsy to confirm it. But they couldn’t do the biopsy until after the new year. It’s hard to hear, “We think you have cancer. Now go on your vacation and when you come back we’ll figure it all out.” Weeks later I was told I had extensive DCIS and would need to have my left breast removed. I opted to have a double mastectomy. A few weeks later a second look at the slides revealed I had some breast cancer in one of the lymph nodes that had been removed (I am now a big advocate for a second opinion on pathology). I was reclassified as having stage II breast cancer. I had chemotherapy; later, a salpingo-oophorectomy.

Almost six years later, I have now found out that I have stage IV (metastatic) breast cancer (details here).

Yesterday I went to an appointment with my local oncologist. I go to see him every two weeks right now to review bloodwork and to discuss dosing for the next round of chemotherapy which starts tonight.

The concept of “good news” has been completely redefined since my new diagnosis. There is no cure, so I can’t hope for that. There is never going to be a day I am not aware of running out of time. Now “good news” gets defined as stable disease. If you’re lucky, and the chemo is working, good news can even mean reduced disease. Now I hope for that.

I look at my oncologist’s face when he walks in the room. I scan it for signs of what kind of news day this will be. The day he told me about my metastasis I read his face. When he walked in that day I asked him how he was and he said, “Not good.” I assumed it was something about him, his family. I immediately starting worrying about the bad news he was going to tell me about someone else. But it was my bad news. It was my nightmare.

I never used the word cured. I never said it. And I don’t like when others do with my kind of cancer. I always prefer the technical terms NED (no evidence of disease) which means it may be there, but we can’t detect it with the tests we have done. I don’t even like the term “cancer-free” for my particular cancer… again, there might be cancer there, but just not enough to be detected or can’t be with the tools used.

Five years had come and came and gone. Even nurses in other specialties would say at my checkups, “Oh! Five years! That means you’re cured!” and when I’d explain to them that it actually didn’t mean that at all with my kind of breast cancer they would look at me quizzically.

“SEE?! I told you!” I want to go back to say to all of them. I was vigilant for a reason. It “shouldn’t” have happened based on the statistics, the predictions. But it did. And now the only life I’ve got is spent dealing with it.

……………..

I watched my oncologist’s face yesterday. We’ve had some bloodwork results in the last two months that have been a good first step but he hasn’t been willing to budge much on declaring that this chemo is working. One or two data points are not enough for either of us to feel confident, actually. But yesterday we got our fifth data point.

I still have metastatic cancer. That isn’t going to change.

But I have some news I can finally share: my bloodwork is showing “indisputably” (in the words of my doctor) that my cancer is shrinking. The chemo is working. The pills I’ve been swallowing, seven or eight a day for seven straight days at a time, in alternate weeks, are doing what we’d hoped. The cancer is still there. But it’s smaller. But it’s responding. It’s been consistently trending down since I started on Xeloda. Now, with more than a few data points, we can finally characterize the effect and I can share it publicly.

……………………….

So what does that mean? I know that’s the question most will ask. It simply means this is the chemo I stay on for now. It means that I just keep doing what I am doing. I’m not “cured” or “feeling better” or “cancer-free.”

It means that modern science and pharmaceuticals are giving me some time. For today, the cancer is responding, shrinking. And in the land of stage IV cancer, that’s unmitigated good news. Make no mistake, it’s no Christmas miracle. It’s not happening for any other reason than the fact that I am aggressively taking as strong a dose of this drug as I can tolerate, and it’s doing its thing.

Six years ago I went on Christmas vacation and feared for my life. I was scared and confused and miserable. Now, six years later I’m in a much worse place vis-a-vis cancer but my mindset is different.

I’m coming to terms with accepting the life I have — the one I thought I’d have is gone. I have created a new one. The best one I can.

For today, I celebrate the good news. I will go to my children’s school holiday parties. I will smile. I will make memories. I will not focus on side effects. I will find beauty in something small.

I will savor the things I can do today.

December 12th, 2012 §

Tuesday’s visit with my oncologist at Sloan Kettering was informative, as always. However, the big question can’t be answered: what is the trajectory of my stage IV cancer?

There will be no answer to that for now.

We start with a chemo. We see (through bloodwork and PET scans) how the cancer responds. If it responds, I stay the course until the treatment stops working or the side effects become untenable or dangerous. There is no way to know how long that will be. Any particular chemo could be ineffective from the get-go. It could fail after months. It could fail after years. Then you go to the list of options and decide on a next chemo regimen. This decision is not always easy; you can’t know which one will be best for you. It is often educated guesswork at best. There can be many chemotherapy options and in the end, I will probably try many/all as each one eventually fails. I’ve talked to women who have gone through more than eight different chemos in the treatment of their metastases. One thing I know is that chemotherapy in one form or another will be a part of my life for the rest of my life.

There is also no way to know if you will tolerate a chemo regimen well. Side effects can be dangerous and variable. Sometimes side effects are serious enough that you must discontinue using a particular drug even if it’s effective in reducing the cancer. As you can imagine, this can be a heartbreaking proposition: find something that works but you are unable to take.

As you know from my last post I have been struggling with HFS (Hand/Foot Syndrome) from the current chemo, Xeloda. I had done some research and found some studies indicating that the selective COX-2 inhibitor and anti-inflammatory drug Celebrex has been used with some success in helping reduce the severity of HFS in patients taking Xeloda (and a few other specific chemos). I had reduced my daily dose of chemo from 4000 mg to 3500 mg for this 5th round (7 days on, 7 days off) to see if the HFS improved with a slightly lower dose. Of course it’s scary to reduce the dose of your chemo but I’ve tolerated the maximum dose for a good number of rounds. It’s normal to need to reduce the dose as time goes on.

My oncologist agreed that the Celebrex was a good thought and definitely might help the HFS. There are risk factors associated with the use of the drug but we both agree that it’s worth the small risk. So I am starting with 200 mg once a day to see how I tolerate the Celebrex and if a low dose helps I will stay with that. If needed, it can be increased to 200 mg twice a day. My hope is that the Celebrex helps the HFS and allows me to go back to the higher 4000 mg (8 pills) a day chemo dosing for the next round.

In the meantime I continue with frequent moisturizing of my hands and feet (at least 10 times a day) with a variety of lotions including shea butter, Eucerin, Aquaphor, and more. I stay away from water, do not apply heat on hands/feet, wear socks and soft shoes/slippers, and wear gloves as much as possible. My feet have been doing very well, my hands holding steady and actually do seem improved today. Here’s hoping!

I know this was a technical discussion today but I want to share it for other people in treatment who might be able to ask their doctors about Celebrex if they suffer from HFS with Xeloda. I also hope that the explanation of chemo and prognosis will be informative.

I continue to do as much as I can everyday and when people see me and say, “You’d never know what you’re going through right now,” I take it as a compliment. I was busy today with routine dentist and endocrinology appointments… you can’t ignore the rest of your body when you are treating cancer. Many other body systems will be affected by the cancer and chemo. My thyroid has been holding steady but shows signs of needing another medication adjustment. Bone treatments like the Zometa infusion I take can cause problems with jaw bones. It’s important to keep a watchful eye on your whole body and not use cancer as an excuse for ignoring routine checkups. That’s my loving nag for the day… stay vigilant with your healthcare appointments and thanks for all of your support.

December 10th, 2012 §

I wake up in the middle of the night with a start:

Heart racing, breathing fast.

It was a dream, I soon realize. What I fear is not true.

The despair, the nightmare, the horror.

All of it was a creation of my mind.

In the dream I was searching for him.

He was gone.

He just disappeared.

My child jogged off into the woods, his identifiable gait

Seen from behind,

Tennis whites lit up the woods–

But where was his racquet?

I realize now in the dream he didn’t have it.

He ran off never to be seen again.

Did not get to his destination.

I searched. I could not find him.

I failed him.

I quickly erase the fiction from my mind,

It’s not true I tell myself:

It’s a dream.

Focus on something else.

It’s 12:56 AM.

My heart settles back to its rhythm

I hear the rain,

My children are safe in their beds.

I can relax now.

But ease does not come.

My fear is misplaced.

The nightmare still persists.

The reality is a different image.

There is a nightmare.

A waking one.

One that’s real and true, one I cannot shake off with time, or more sleep, or distraction.

My nightmare is loss, it is my children out of my grasp, it is separation.

I still fear all of those things.

But it is I who will wander off into the unknown

Leaving others behind

Waking in the middle of the night with only an image of me,

Fleeting,

As they search for me in vain.

I will be there, with them, but only in memories.

It will have to be enough.

But I know it won’t be.

After all,

This is what cancer nightmares are made of.

This is what grief does.

I cannot do more, be more, than I am right now.

But I can want more.

It is a parent’s prerogative.

I am greedy.

I make no apologies for wanting to see the things I want to see,

Wanting to share the things I want to share,

Wanting to live the life I want to live.

This is what I want.

This is what I hope.

This is what I dream.

December 8th, 2012 §

I realized it’s time for an update… but confess I’ve started and stopped this one a few times. Somehow when things are going along somewhat easily it’s easy to do the updates.This is the first one I’ve had to discuss side effects and I hesitated a lot about what to write and whether to post it. I wasn’t sure about talking about these things lest they be seen as complaining. My goal has always been to educate and inform above all.

Friends on Twitter assured me that talking about the daily in and out of chemo treatment for metastatic cancer is important. Not only are they learning what it’s like, but it tells people what I’m dealing with and what activities might be hard for me on a daily basis. One Twitter follower also said that for those who have family members with this disease and might not be forthcoming with detailed information, some of these updates give them an idea of what it might be like for their loved ones. While treatments and surgeries vary so much, I thought this was an excellent point.

I also have decided to post this information because I know other metastatic patients will find it through search engines and maybe it will help them. So… I’ve opted to continue to share these things. It’s the reality of cancer. It’s the reality of MY cancer.

I’m struggling at the moment with Palmar/Plantar Erythrodysesthesia or Hand/Foot Syndrome (HFS). This is a common side effect of Xeloda, the chemo I am currently taking. In short, the capillaries in the hands and feet rupture and the chemotherapy spills into the extremities. Redness, swelling, burning, peeling, tenderness, numbness and tingling can accompany it. While it does not always start right away, once you’ve had a few rounds it’s likely to be a cumulative effect.

After receiving another monthly IV infusion of Zometa to strengthen my bones on Tuesday, I started a new round (#5 for those of you keeping track at home) on Thursday night, and had to decrease my dose slightly to deal with the HFS. Rather than 8 pills a day (4000 mg) I’m on 7 now. The hope is that the HFS will stay at its current level and not progress on this dose. This is what feet start to look like with HFS:

It can get much worse than this with blisters and ulcerations but mine is not at that stage. If it were to reach that point we’d have to stop chemo until it healed and then re-introduce it. Driving was one of the hardest things yesterday, the pressure from the steering wheel (or anything against my hands) was difficult to tolerate. I wear cushiony gloves most of the day now and follow all of the guidelines to keep it at a minimum. My hands are more sore and sensitive than my feet this week but not as red as my feet. Thankfully while I could not hold a pen during most of the day, I could still do some typing. A long-term side effect of this particular drug is the potential to lose your fingerprints. I see an episode of CSI coming on that one! An article about the difficulty traveling with such a condition appears here.

Loss of appetite continues to be an issue but my weight has stabilized after a 20 pound loss in the first 6 weeks. It’s weight I needed to take off anyway, actually. I must eat twice a day when I take chemo and once I start eating I usually do just fine. I do better eating in the evening. My blood counts remained fine even during the weight loss and my instructions have been to “keep doing what I’m doing.” The one thing I can’t do is exercise at the moment. Friction on my feet can exacerbate the HFS so for now it’s not happening. A soon as the rib in my shoulder heals I will be trying to get back to Pilates class.

I’ll be back at Sloan Kettering on Tuesday, 12/11 to meet with my oncologist. We’ll evaluate the HFS by then and talk about ways to help me deal with it and make me more comfortable. We will also then be talking about what dose I will take for my next round and also start talking about when my next PET scan will be.

That’s the update for now, I’m still doing everything I can and am out and about as much as possible. I still bring the kids to the bus in the morning and try to do errands like the grocery shopping as often as I can. I ask for help with things that really are tough on my hands like stuffing the holiday cards or doing laundry or dishes. Even small tasks give me a sense of accomplishment and normalcy so while the weather holds I continue to do them. Once ice and snow set in and my concerns about slips and falls and bone breakage rise I will get help with more of the outdoor things.

I’ll have more pieces coming out on HuffPo shortly; thank you all for the excitement and congratulations about that new venue. My piece about what to do as soon as you are diagnosed, especially in regard to children, will be the next one they post. After that I’m looking at writing on the topics of bravery/inspiration, the situation when people you barely know take your condition as seriously as if they were family members, and the story of how I found out I had metastatic cancer to begin with. If you have any topics you’d like to see a piece about leave a comment or email me via the contact form and I’ll definitely take it into consideration!

Thanks for all of the support this week.

December 2nd, 2012 §

For those who were asleep in the wee hours yesterday morning and have asked, here is a link to the radio interview I did with Robin Kall yesterday on WHJJ. It’s about 15 min long… to listen click here.

If you are in a radio mood, the post containing the link to the HashHags interview I did a few weeks ago is here.

November 30th, 2012 §

Good news first: I’ve been asked to be a blogger for the new Huffington Post section called Generation Why which focuses on young people and cancer. At first I had to look to my left and right and ask, “Me?” because I haven’t really thought of myself as young in a while. But certainly issues facing people like me with cancer can be unique. The necessary pushes and pulls of being social for my children with the always magnetic desire to just be alone will be one theme I will write about for sure. A friend commented that he was “impressed” I was writing for HuffPo… I will have to remind him that Jenny McCarthy does, too, so it might not be as impressive as he thinks!

That said, I’m very pleased to have a wider audience for my writing. I hope the readers and commenters will be as nice as you all have been. The first post should go up this week and I’ve decided to have them use this week’s post “Alone” as my inaugural piece because the response to that one was overwhelming. I might as well start with a bang! I hope that piece will be one that represents my perspective well.

So.. the bad news is not terrible, but here is the latest news. While I started with very good tolerance to the 4th round of chemo, the end of the round ended up bringing hand/foot syndrome (palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia) from the Xeloda. Hand/foot syndrome is not the same as neuropathy (though it may include some of those symptoms), which many people on chemotherapy experience.

Hand/foot syndrome is associated with a few particular drugs, Xeloda is one. The capillaries in your hands and feet leak and/or rupture, causing the chemo to spill into the extremities. This causes them to be extremely red, swollen, painful, sensitive to touch, cracked, peeling, and potentially ulcerating. Numbness and tingling also accompany the condition.

For the past month I’ve been trying to keep these effects at bay, but eventually the toxicity builds up. Fine motor activities like tying shoes are hard at the moment, anything that touches/puts pressure on hands and feet. Thankfully I have some shoes with furry insides and cushioning. Socks must be worn 24/7 and slippers at all times. Holding the steering wheel is uncomfortable but doable, thankfully. So many people have suggested I should do something relaxing like go for a massage or manicure/pedicure. Unfortunately between the broken ribs and a “no touching” order for hands and feet these things will have to wait!

I had to skip my last dose (there are 14 in each round right now) of chemo yesterday to prevent a flare. The plan will be to reduce the chemo dose to 3 pills in the morning and 4 at night next round to see if that will be enough of a reduction to stop the progression of the syndrome. If it isn’t, we’ll reduce again. The reduction in dosage is not rare. My understanding is that tolerating 4/4 for 7 days on and 7 days off for more than a few months is pretty unheard of.

I’ll have bloodwork on Monday, December 3rd and then meet with my local oncologist on Tuesday the 4th for a strategy meeting and check on the hands and feet. I’ll also receive my monthly IV of Zometa for my bones at that time.

…………………

Tomorrow (Saturday) sometime between 7-8 AM I’ll be on Robin Kall’s radio show which streams at www.920whjj.com. Stay in your PJs and join us! I think it will be after 7:15 sometime as the 2nd segment.

…………………

Thanks for the continued support and I’ll have a more creative post this weekend.

November 24th, 2012 §

I can see how isolating metastatic cancer can be already.

It has become hard for me to be around other people.

I find myself hiding as much as possible.

When I am in the company of others my mind wanders.

I can’t focus. I feel the need to retreat.

For the time being I just can’t relate to others’ lives which only 6 weeks ago were so similar to my own. Now… we are a world apart.

It’s not their fault. It’s just that circumstances make it so that I am selfish. I try to conserve my energy as much as I can.

Already I can see relationships suffering. There is a fine line between giving space and putting distance. Some are already dropping away, and we’ve only just begun. Others have risen to the occasion and helped more than I could have dreamed. Only true friendships are going to make it under these circumstances. Sometimes the isolation comes from being shut out. Sometimes it comes from locking yourself away.

Phone calls go unanswered, emails often do too. Thank you notes don’t always get written, social commitments get canceled or never scheduled in the first place.

I know that people cannot truly understand.

I don’t want a support group right now because metastatic cancer has a wide range of outcomes. I don’t know if I will be in a rapidly progressing group or not. I don’t know whom to look to that is “like me.” There is no way to know which group I will be in, who my peers are.

Right now I am very sensitive to death, to pain, to suffering. It’s very hard for me to see right now. I’m too raw. I just don’t think I’m ready for a group. But I won’t say I never will be. I need to talk to my oncologists about whether they have patients like me.

It’s difficult to listen to people complain about trivial things, normal things, things I was complaining about two months ago.