February 28th, 2012 §

I remember the old days.

I remember the old days.

I remember the way my father looked at my mother.

I remember when they were married and living together.

Those days are no more.

……………

I remember when they danced in the living room as my brother and I watched.

I remember my mother clicking her tongue to the beat, waving her arms in small circles, wrists cocked, like windshield wipers gone awry.

I remember my father smiling, biting his lower lip, chin extended outwards, hopping and bobbing to the beat.

……………

I remember when he would ask me, “Isn’t she cute? Isn’t she adorable?” and playfully pat her on the rear.

I remember the way she said her heart went pitter-patter when he walked in the room.

I remember when she listened to talk radio as she cooked, the wire antenna taped to the underside of a cabinet so that her favorite station’s reception would be strong. Masking tape marked with surgically precise lines identified the stations she would tune to.

The radio always got turned off when he pulled in the driveway.

……………….

I remember falling asleep in the backseat of the car.

I remember waking up, startled, not realizing where I was.

I remember them twisting from the front seat to say, “Surprise! We brought you to see the panda bears at the National Zoo!”

I didn’t think life could get any better than that.

……………….

I remember the fights. The yelling. I remember newspapers on a kitchen chair, shoes on the table. I remember so much more.

I remember their wedding anniversaries on Christmas Day. Nothing open, nowhere to go, no good way to celebrate.

I remember cardboard cartons of Chinese food.

……………….

I remember the beginning of the end.

I remember their being close to the precipice once before, my relief that it went on.

I remember it finally being the end.

……………

There is a small guest room in the house that I now call my father’s. It used to have a crib in it; now, as my three children have grown, it’s been replaced with a twin bed.

I know that in the closet there used to be a small white leather briefcase.

Inside that briefcase is a Viewmaster and two rows of dual-image slides. These are my parents’ wedding photos: three-dimensional images that get popped into the Viewmaster and looked at through light.

I haven’t looked at them in years; suddenly, it’s the only thing I want to do.

My mother’s brother, so young in those images, died in his 40s. My father’s brother, now dead too. Neither has living siblings, nor living parents. There are so few of us in the family left now.

…………….

I see the disbelief, how people are unwilling or unable to accept that something that lasted for so long is over.

It scares them.

Like cancer that recurs after a decade, it means we are vulnerable even after a seemingly safe waiting period has elapsed.

Divorce can happen after 50 years.

……………..

“They’ll get back together,” one of my doctors insists whenever I see him for an appointment.

“No,” I say, “they won’t.”

…………….

“Did you see it coming?”

“Do you think they’ll reconcile?”

“What happened?”

“Are you surprised?”

…………..

“You’re the writer,” my mother says, “Maybe you’ll write about this.”

……………

I took my mother’s wedding ring out of the drawer this morning.

She gave the ring to me years ago when Dad eventually bought her the diamond one he hadn’t been able to afford when they got married.

I rubbed the ring, imagining the two young people who stood exchanging vows.

Hopes. Dreams. Compromises.

A lifetime together. Their lifetimes together.

Until now.

I know my mother has a receipt for that ring, 50 years old, in a file.

I know where that file was when she lived in the house.

But now she doesn’t live there anymore.

Her papers are in boxes in storage.

Somewhere in a box in my mother’s apartment building there is a receipt for the ring my father bought for her.

That paper will outlast their marriage.

……………

I remember when that ring proudly announced to the world that my parents were happily living together.

Those days are no more.

December 14th, 2011 §

My mother retired a few years ago. For much of her adult life she was a psychologist specializing in grief and loss, death and dying. She wrote her dissertation on the impact a child’s death has on family dynamics. She used a case study method, doing in-depth interviews with surviving family members of various tragic events that happened. In one case, a house fire killed a child; in another, a baby died of SIDS.

They were heart-wrenching stories, and even as a child I could tell this was “heavy stuff.” Of course I couldn’t comprehend the magnitude of a parent’s love for his/her child until I had my own; but, I realized in reading the transcripts that grief is a multi-faceted emotion. And that loss is a process.

Having my mother work in this somewhat unusual profession was excellent training. I learned at an early age so much about sympathy, empathy, guilt, regret, and the discomfort our society feels about the subject of death. Despite the fact that it is the one thing that unites us all, the one common thread in all our lives, most people just don’t want to explore the subject of death. It makes people uncomfortable, makes them squirm, and almost universally makes people change the subject.

When you have had a death in the family, people don’t know what to say. In fact, it is likely many people won’t bring it up. Often, they worry that they will be reminding you of the tragedy, as if you have forgotten it. Anyone who has experienced a death of a loved one knows this isn’t true. The deceased person is never far from your mind, from your heart. And more often than not, you want to talk about that person. My mother taught me this. She taught me that people will never be upset if you remember and talk about the person they loved; it means their legacy lives on. Everyone wants to be remembered. You honor this desire when you talk about a deceased person.

I have said many times that growing up with my two parents was the best training for my string of illnesses through the years. While cancer has been the most serious, it has by no means been the only medical challenge I’ve had. But having a surgeon for a father and a psychologist for a mother was perfect.

I was able to digest complex medical information. When surgeons told me what needed to be done I could weigh my options methodically. I could weigh options of treatment and ask good questions to determine the best course of action for me. I could read pathology reports with ease. And then I could be insightful into my emotional response, being introspective and analytic

And being insightful and analytic about a life-threatening disease means confronting mortality. Often I hear stories of people dying without a will. In fact, often it’s only once people have children that they feel sufficiently motivated to create a will, because their love for their child (and making plans for a guardian) is the only thing that can make them confront this fear.

Often when I was in the midst of chemotherapy I wanted to have conversations about the “what ifs.”

What if they didn’t get it all.

What if the chemo doesn’t work.

What if the cancer comes back.

What if I get another (worse) kind of cancer from the chemo.

What if I die.

No one really wanted to talk about the last possibility even though it wasn’t outlandish. (Interestingly, people are very intrigued with my recurrence likelihood and mortality statistics… they view the numbers as easier to talk about in the aggregate rather than just discussing my own death).

I viewed talking about my death as responsible. I wanted to make sure Clarke understood that if I died, I wanted him to find another wife. I wanted him to be happy and loved. I wanted our children to have a mother to love them. Unsurprisingly, my greatest worries centered on my children.

I sat with a friend at coffee one day and voiced some of these concerns. With 5 children of her own, my friend is an amazing wife and mother in all respects. At first she was resistant to talk about my death with me. She didn’t want to entertain that notion. But I pressed the issue. And finally she looked me in the eye and said, “If you die, I promise I will watch over your children. I promise I will make sure they have the right person love them and raise them. I promise you that I will make sure that happens.” I think she figured it was the fastest way to shut me up. I think she figured she would agree to anything I was asking just so we could get off the subject. But at some point I think she realized that it was really important to me. I wasn’t going to let it go. And I wasn’t going to be able to get past it until I felt they would be safe and watched over. So she told me what I needed to hear. And I know she meant what she said.

Like a balloon slowly deflating, I felt my body go lax. Finally, I could let it go. She had promised me she would do for me what I wanted. I could trust her, and I could move my worry to something else. She did more for me by making this promise than she will ever know.

Here is one of the things I’ve learned from my mother: When someone you love is talking about death, don’t change the subject. Don’t trivialize their worries. Don’t say, “Let’s not talk about that now.” If they want to talk about it, it means it’s important to them, it’s weighing on them.

Focus on the fact that while we don’t need to sit around thinking about death all the time, there unfortunately might be times in our lives when we might not be able to think of anything else. If you haven’t experienced that, I applaud you. But sooner or later, you or someone you love will.

December 2nd, 2011 §

I’m working on a new piece about grief during the holiday season, but really want to re-share this short post for those who missed it. I actually re-read it from time to time to remind myself of a valuable insight I had with two of our three children. This was originally written two days after their grandmother was killed in a car crash in 2009.

……………………………………………………..

Children are different.

From adults.

From each other.

I had to give two of my children different directives this morning:

One I told, “It’s okay to be sad.”

One I told, “It’s okay to be happy.”

I needed to tell my 7 year-old son that it was okay to cry, to be sad, to miss his grandmother.

I miss her too.

And it’s okay to let your emotions show.

It doesn’t make you a sissy or a wimp.

What it does make you is a loving grandson.

A grieving boy.

A bereaved family member.

But my ten year-old daughter needed a different kind of permission slip today.

I sensed she needed permission to smile.

To laugh.

To be happy.

I needed to tell her that it was okay to forget for a moment.

Or two.

To forget for a few moments that Grandma died.

It’s okay to still enjoy life.

The life we have.

Grandma would want that.

I told her that Grandma loved her so much.

And was so proud of the person that she is.

I reminded her how Grandma’s last phone call here last Sunday was specifically to tell Paige how proud she was of her for walking in a breast cancer fundraiser with me.

It’s okay to still feel happiness.

And joy.

It’s okay to let that break through the sadness.

Children are different.

But they take their cues from us.

I know my children.

I know that this morning what they needed from me was a sign that it was okay for them to feel a range of emotions.

It’s healthy.

Because what we are living right now is tragic.

And confusing.

And sad.

And infuriating.

If it is all of those things for me,

It can only be all of those things and more

To my children.

October 11th, 2011 §

Regular readers of this blog know that after more than 49 years of marriage my parents have decided to separate. Over the past few months I’ve memorized a new phone number for my mother. I wrote her new address on a piece of lime green note paper and pinned it to my bulletin board. I’ve repeated stories about my children in the past few weeks twice– first to one of my parents, then to the other.

But six days ago I had the unique and unpleasant experience of driving up the driveway to the house they still own knowing my mother would not be standing out in the driveway waiting for me to arrive.

I was greeted by my father, instead, alone ushering me into my mother’s garage bay, the one she still uses when she has occasion to be at the house.

I walked inside and looked around; her desk in the kitchen was mostly bare, so too some of the walls in each of the rooms. The refrigerator held less than half of what it usually would; even my beloved Nespresso machine was no longer a fixture. I didn’t even go in many of the rooms. I didn’t want to see all of the changes.

Things were different, and not only the things.

Seeing my mother needed to be planned, coordinated. No longer was she only as far as a loud yell down the hall. No more could I stalk her around the house instigating conversation in an attempt to catch up on every little thing we’d missed since our last phone call.

That night I saw her new apartment and everything really started to sink in. By the next morning when I awakened I was overcome with emotion. I went downstairs to the kitchen and still half-expected her to be there, reading the paper, re-heating a cup of coffee that might have been put aside and gotten a chill. I still expected to see her the way I almost always did in the morning: dressed for the day, a full face of makeup save the trademark cherry red lipstick she would wait to apply until she had finished her morning cup of coffee.

For now phone calls via speed dial and texts would have to tie us together.

It wasn’t the same, of course. It couldn’t be. It can’t ever be.

I did keep a constant refrain in my head: my mother is alive, my mother is healthy. I am thankful for that.

She was not under the same roof I was anymore, but she still resides where she always has: in my heart, as close as she can be.

October 9th, 2011 §

Last Wednesday we took Tristan to Shriners Hospital for his checkup with his spine and hand team. He goes every 6 months for monitoring, in particular to make sure the tilt of his head has not increased. His spinal deformity consists of hemivertebrae (vertebrae that are only partially formed) and vertebral fusions (ones that are stuck together). This combination results in his case in something known as a disorganized spine.

As an infant his head was quite crooked on his neck.

During the ensuing months, the tilt measured 25-30 degrees. The severity of the situation increased and Dr. Randal Betz told us if the curve progressed we would have to intervene with surgery to fuse the vertebrae in a straight position. His neck growth would be halted; while his body would mature his neck size would be that of a toddler. He would have no mobility in the neck after the surgery. We prepared ourselves for hearing the news.

We continued to monitor his growth. As he began to sit, and then walk we watched as the neck grew. His two hemivertebrae were growing in such a way that they were balancing each other as he grew. Had the pizza slice-shaped wedges been wide on the same side, surgery would have been inevitable. Because they were on opposite sides, this “z-curve” worked to his advantage. By the time he was a toddler his head was straighter.

Though his neck is short, and always will be, it has continued to grow. Physical therapy since birth has kept his muscles stretched and strong. Weakness on one side of his body is imperceptible.

This week his x-rays showed that the tilt once at 25-30 degrees is now less than 8 degrees. His eye sockets and lower jaw are almost even. The three points he has mobility in his neck are stable and should be sufficient to prevent extraordinary wear. He’s doing as well as he possibly can be, given his anatomical issues.

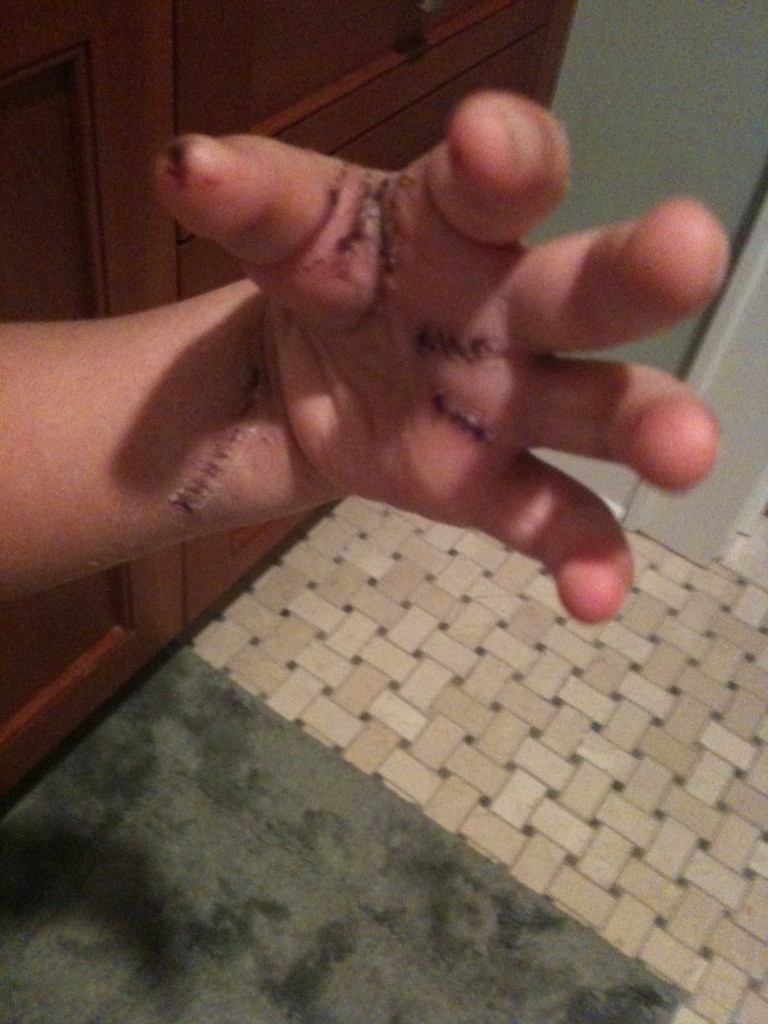

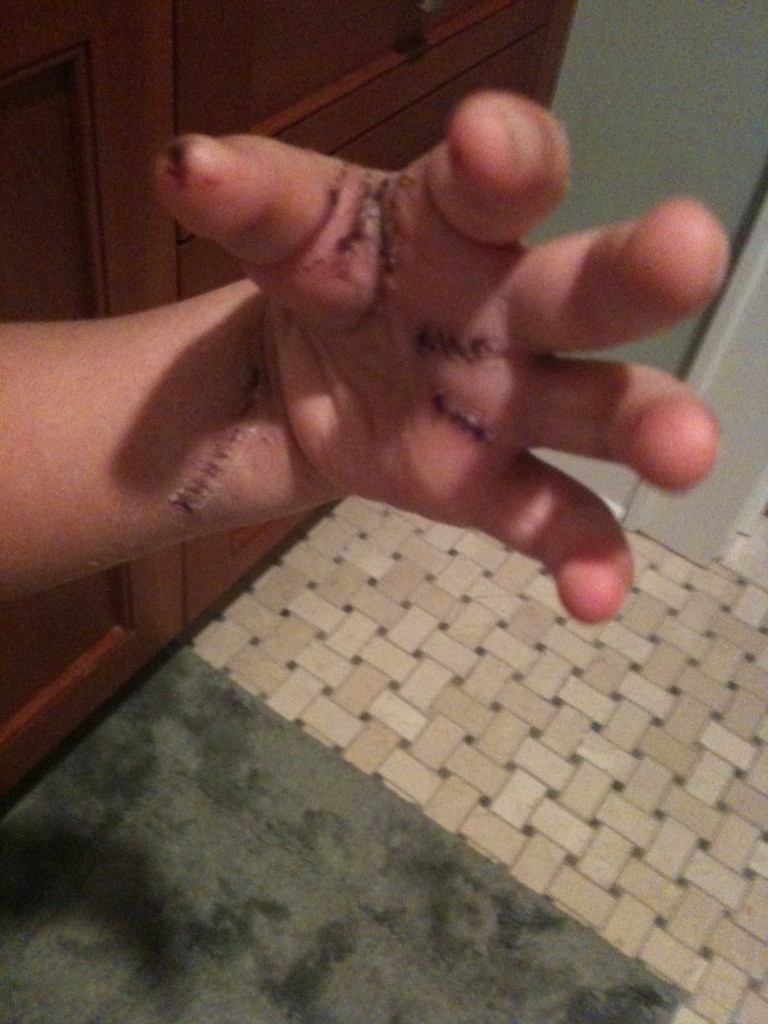

We next had Tristan’s appointment with his hand surgeon. He, too, was pleased with the results of Tristan’s three-pronged surgery last March (you can read about Tristan’s hand deformities here including his lack of a flexor pollicus longus muscle on his left side which makes his thumb unable to bend ). A flexor digitorum superficialis tendon transfer, ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction at the base of the thumb, and a 4 flap z-plasty of the thumb index web space were all successful. The large scar on his wrist is fading and it’s hard to believe it looked like this.

Here he was this week showing that hand with his upper extremity surgeon, Dr. Scott Kozin.

His left thumb will never bend, and the hand will be weaker because of it. He is a lefty, so it does affect his fine motor skills. But we continue to do hand therapy with him and it’s made a world of difference. Each Monday and Tuesday this 5 year-old is doing his therapy sessions at 6:30 A.M. before he heads off to kindergarten. That smile is always on his face. He never complains. He got a great report and we left Shriners happy and exhaling for another six months. We saw many friends there and it’s always like a family reunion. We’ve been through a lot together and we are grateful for their continued support and care.

I do want to mention one thing we learned at this visit. Shriners specializes in orthopaedic and spinal cord injuries; when children have traumatic spinal injuries, this is where they go. Tristan’s spinal surgeon told us there are two activities that they recommend children avoid because the risk of spinal injury is so great (this is for all children, even who do not have any defects): trampolining and riding four wheelers (ATVs). Those two activities have such a rate of injury that the surgeon does not allow his own children to participate in them. I share that information because it was new to me; we do not own either piece of equipment because Tristan is not allowed to do either but we were not aware that those activities were so dangerous to all children.

September 27th, 2011 §

September 29, 2010

Most of you probably read the title of this post and thought I was going to write about the guilt we may feel as parents over the course of our children’s lives when we can’t be there for every event they want us to attend or say no to things we know they might want to do.

But that’s not what I mean by “Mommy guilt.” Instead, it’s the feeling I have today because my mother is coming to visit.

I feel guilty because I have a mother who’s alive and many people I know do not.

I commented on Twitter this morning that my mother was coming for a few days. Author and friend Katie Rosman tweeted back “jealous.” Katie and I actually met because of the moving book she wrote about her own mother’s death five years ago, If You Knew Suzy. I wrote a blogpost about that book; in it I shared personal feelings about having cancer and what my legacy might be for my children.

But there was more.

Katie’s mom is dead. So is my husband’s mother. So are the mothers of many of my friends. And as I go through middle age this will happen more and more. And someday it will happen to me.

Every time I drive the fifteen minutes to the Amtrak station to pick Mom up (when she and my father don’t arrive by car here together) I think about the night I drove to get her at the train station the first time she came to visit after Barbara died.

When I saw my mother step off the train that night last year I almost had to look the other way: it was like looking at the sun.

The sight of her was

so bright,

so intense,

so welcome,

so wonderful,

that I almost had to look away for a moment.

The guilt over being able to see her step off that train and into my arms again overwhelmed me.

And so, today, when I see her again, I will hold her, kiss her, hug her. I’ll hug her for an extra moment and think to myself: this is for all of you. This is for all of you who have lost your moms and can’t do this simple act anymore. A way I can honor her and you is to appreciate these times we have together because I know there are so many who would give anything to have one of these moments with their mom again.

September 27th, 2011 §

A previous discussion about inspiration and setting an example provoked my friend Laura to write to me, “If something ever happens to me where I have to dig deep to find that strength that you have found (and shown), I will think of you. Often. And re-read your blog. Often.”

This was the highest compliment and I appreciated those words immensely. Her words got me thinking.

So many of my friends have mothers who’ve had cancer. In college, my two closest friends, Alex and Deb, both had mothers who had breast cancer. Somewhere in that experience was an expectation for them that someday, inevitably, they would have it too.

It was many years before my own mother did. And then right on her heels, so did I. Before Alex and Deb did. And so, like my mother was for me (see Everyone Needs a Trailbreaker), I suddenly became the trailbreaker for my best friends.

I’ve gone through some cancer scares with friends and acquaintances over the past three years. I’ve sat in waiting rooms, taken phone calls, written emails, met with women in person. I’ve helped friends, strangers, and friends of friends.

When I was young someone teasingly called me a walking encyclopedia. Somehow it still seems true. My husband only half-jokingly shakes his head when he hears some of the questions people ask me. He sometimes says, “They do know you’re not a doctor, right?”

I know that I’m the first of my friends to have breast cancer. And have it “bad.” The whole nine yards. That experience comes with responsibility. I know that having cancer at 37 means that I will be that resource, that friend, that support system.

In the future, others will need me. Friends will ask me how to help, what to do, what things mean.

There is a lot of pressure coming my way and I think about it already: what if I let them down?

That’s the kind of person I am.

I am already worried not only about getting through my own experience; I’m worried how I can help my friends if their time comes.

And statistically it will.

I’m worried who will be next.

I’m angry someone will be next.

I want to be the lightning rod.

I want to take in on for them.

I want to protect them.

Laura, I want to protect you:

I don’t want you to have to read my blog for strength.

I want you to read it because you want a window into a world you never have experienced. And never will.

That is my greatest hope, my greatest dream.

If I could sleep, that would be my dream:

To keep you all safe.

September 16th, 2011 §

September 16 is the anniversary of the death of two women I loved: my paternal grandmother, Sara, and my mother-in-law, Barbara.

Bubbe (Yiddish for “grandmother”) died in her 80s, many years ago, after her health had begun to fail. She lived in Israel, and I did not have the opportunity to see her one last time before her death. In stark contrast, Barbara died only weeks after I last saw her, laughed with her, attended a family wedding with her. We had no earthly idea she would be killed in a car crash, of course, no time to prepare ourselves for hearing the words that rocked our world.

It was Open House at my children’s elementary school that night, and when the phone rang I didn’t recognize the voice. It was my husband’s voice, strained, hiccuping, sobbing. I didn’t understand at first; I couldn’t process what he was saying. In the same way I quizzically furrowed my brow when I sat in the basement of my daughter’s school in New York City and the principal announced on that first day as our preschoolers were upstairs, “A plane has hit the World Trade Center,” I again heard information and my brain responded with Does Not Compute.

Anticipatory grief is real. A diagnosis, a doctor’s report, an assignment to hospice– all are ways others try to prepare us for the death of our loved one. With each step, with each caution, with each added conversation we start to get our minds used to the idea that it may be the end. Like a threadbare shawl we continue to wrap ourselves in, each time we are comforted less and less by others’ words of reassurance.

When a death is sudden and unexpected, there is so much to get used to, so much to process. It is a task to make sense of the death, to integrate it into our consciousness. We must unbreak habits. I remember so clearly when my uncle Alan died, I still continued to pick up the phone again and again to share a piece of news. I had to keep reminding myself, “You can’t call him anymore.”

There are so many talks I have missed with these women. There are so many things I’ve wanted to show them, share with them. However, I am so lucky to have had them in my life for as long as I did.

September 6th, 2011 §

The house is so quiet… for the first time ever, all three of my children are out the door before 8:00. Tristan will have half days of kindergarten for the first two weeks so the change from preschool won’t be too dramatic. And yet, somehow with his backpack on, lunch pack clipped to it, it is different. He stands at the bus stop with a bunch of other children from the street; some of them were babies when we first moved here seven years ago. I see the changes in them after the summer more easily than in my own.

These are the psychological stretch marks I’ve written about before. These are the moments you know are monumental. Growth happens in fits and starts, not with smooth, sliding grace. This shift is simultaneously sudden and gradual in its arrival; I’ve been counting the days for the last month, but still the finality of its presence takes my breath away. With Tristan it’s different, his life thus far has been a challenge in many ways (background on Tristan and his physical abnormalities here). We’ve been a team, and worked so hard together. He will continue with OT and PT and need a few modifications in the classroom. But I know he’s going to be just fine.

I’m looking forward to writing again… the last month has been busy with things mostly of the unpleasant kind. But the routine of the fall, the schedules, the calendars give me structure. And with structure comes comfort. I can get through this rocky time. I can create the life I want, the one I need. I just have to keep trying.

August 19th, 2011 §

Much writing comes from pain. Much of mine has.

I initially started this blog when I was dealing with the after-effects of my cancer diagnosis, chemotherapy, and surgeries. Later I wrote about my grief when my mother-in-law Barbara was killed suddenly almost two years ago. Back then — and now once again — there is a line I have always tried to walk between exploring my own feelings about my life and those in it while not divulging too much information about people who might not want to be so public with their thoughts as I have.

I haven’t posted much this month; it’s not just because it’s summer vacation time. I’ve been struggling with some issues and unsure how I can write about them while still allowing those I love their privacy.

I try to be the quiet wheel– you know, the one who doesn’t get the grease. With neighbor disputes, school and coaching situations, I do my best to be neutral, to just get along with people. When it comes right down to it, I just hate drama. I could never go on a reality show because my idea of a great day is one that most would term “boring.” I just want quiet and peace, a good cup of coffee and good health for my friends and family.

But lately that’s not possible and there’s a knot in my stomach all the time. And what I’m realizing is that it’s hard for me to write when I can’t be completely open and honest. It’s hard for me to carve out a part of my life and say “but I won’t touch that subject.”

The varied parts of our lives are intertwined; the strands are knotted. It’s one big heaping mess of togetherness.

And so, I want you to know I’m working on it. I’m trying to figure out how to navigate this time in my life.

August 2nd, 2011 §

I thought they would always be together. I thought it would be until the end. When I look back over the things I’ve written about my parents, a constant theme is always how I can’t imagine them without each other.

And yet, this week, my mother moved into her own condo and began her life apart from my father.

Their dynamic just was not working anymore; six months shy of their 50th anniversary, they’ve decided to separate.

I’ve known for a few months, and the children know now too. In fact, as I write this, my parents are (together) spending a week with Paige and Colin as they do each summer. Nothing, even the decision to move forward apart, comes in the way of that this year.

I’m still a child. Their child.

I’m learning that no matter how old you are it affects you; age is not a protective shield against the hurt that can accompany such changes. Now 42, I have two generations to consider: my parents and my children. At the moment my parents’ health is good; I’ve written before about my mother’s stage III cancer diagnosis six years ago (she is in remission). But I confess, even on their healthiest days I play the “what if” game. I feel I need to always be thinking about the future, making sure I have an escape route. Like a stewardess pointing with a flourish to an exit in the forward cabin, I need to show myself that there is always a way out, a plan should something go wrong.

Even in the face of truly excellent health we’ve learned that life can change in an instant; after all, Clarke’s mother was perfectly healthy when she was killed in a car crash almost two years ago. I did not have a “what if” mentally written for that circumstance– how could I? But I have seen the way a tragedy can change a life in a split second. I think my confidence in what the day will bring has been shaken; I no longer believe that the day shall end as it began, life bookmarked in its progress.

I love my parents dearly; I am as close to them as a child could be, I think. We laugh, we talk, we share. I wouldn’t have it any other way. But the fact we are so close means this new chapter of their lives affects me deeply. How can it not? The very foundation of home life I have know my entire life is gone. I’ve been married for fourteen years; I am not a naive child who thinks wanting to make it work is enough.

And so, I program my phone with my mother’s new contact information; she gets her own entry now. I order change-of-address cards for her, and return address labels. Information now needs to go to two places. Anecdotes about the children need to be recounted twice rather than hearing my voice echo on speakerphone in the kitchen.

I support their decision– how could I not? I want them to be happy, and to achieve this goal they must live apart. But my knowledge that it’s what is best doesn’t make the bitter pill any easier to swallow.

I know a lot about grief and loss. I know that it takes time. This loss is something I’m dealing with, and will continue to, day by day.

July 5th, 2011 §

I met a woman who told me something shocking.

It wasn’t that she’d had breast cancer.

Or had a double mastectomy with the TRAM flap procedure for reconstruction.

Or that she’d had chemotherapy.

What made my jaw literally drop open was her statement that she has never told the younger two of her four children that she’s had cancer.

Ever.

Not when she was diagnosed.

Or recovering from any of her surgeries.

Or undergoing chemotherapy.

She never told them.

To this day– five years later– they do not know.

I like to think I’m pretty open-minded. But I confess, it took a lot of self-control not to blurt out, “I think that is a big mistake.”

I’m a big believer in being open and honest with your children about having cancer. My caveat, using common sense, is that you should only give them age-appropriate information.

When I was diagnosed with breast cancer Tristan was six months old. Of course he didn’t understand what cancer was. Colin, age 5 at the time, understood some of what was happening. I explained to him what cancer meant, that I was going to need surgery to take the cancer out, where the cancer was, what chemo was, what it would do to my appearance and energy level. Using words like “I will be more tired than I usually am. I might feel sick to my stomach and need to rest more” explained things in words he could understand.

Age 8 and the oldest at the time, Paige understood the most when I was diagnosed. She had bigger questions and well as concerns about me (“Will I get it too? Who is going to take care of us? Are you going to be okay?”).

It’s not that I think small children always understand everything. But they are certainly able to sense that things are not “normal.” They can tell when people are acting strange. I think it’s important that they know there is a reason for that change. Children have a tendency to be egocentric; they think that everything is their fault. They may think they have done something wrong if everything at home feels different.

The woman told me she didn’t want to worry her children. She thought it “unnecessary” to tell them. She said when they got older she would explain it. I argue that by keeping her cancer a secret, she runs the risk of doing the opposite: making cancer seem scarier and more worrisome.

If children hear words like “cancer” casually in conversation as they grow up they will be comfortable with them; in that way, they won’t be frightened of them. If they understand the truth of the diagnosis and treatment they are dealing with reality. By hiding the truth, the unintended consequence is to make it seem worse than it is. By not telling children, and waiting until they are older, it reinforces the idea that cancer IS something “big and scary.” After all, if it weren’t, you would have told them already.

I think being secretive is a step backward to the days when cancer was only talked about in hushed tones: the “C” word or “a long illness.” These concepts might seem primitive to us now, but it wasn’t long ago that these vague labels were the norm. By showing our children, our friends, our neighbors, that we can live with cancer, live after cancer, we put cancer in its rightful place.

To me, the deception that goes on to lie to children about where you are going, what you are doing is lying about a fundamental part of your life. Cancer isn’t all I am — but it is a part. And it’s an important part of my medical history. If for the past 3 years I’d covered up where I was going and what I was doing, the web of deceit would have been extensive. I can’t (and won’t) live a life like that.

Further, I think it’s a poor example to set for my children.

Lying,

covering up information,

and omitting important information are all wrong.

With rare exception, the truth is always best.

Presented in the proper way,

commensurate with a child’s age,

a difficult situation can be not only tolerable but surmountable.

It takes work. It takes parents who can manage not only their own emotions about having cancer but also be involved with helping their children cope with it. It’s more work, but it’s worth it.

I think that woman made a mistake. I think her decision was harmful. I am sure she thinks she was doing her children a favor. I totally disagree. I think keeping this type of information from children “in their own best interest” is rarely– if ever– the right thing to do.

April 9, 2010

July 5th, 2011 §

Last summer I wrote the following piece about an upsetting interaction I had with a bookseller. It remains one of the posts that readers mention and still ask me about. The topic of children and death must be a touchy subject for most. I guess because I grew up with a mother who was a psychologist specializing in these topics I have never felt uncomfortable talking about them. Let me know what you think.

……………………………….

June 23, 2010

School is out for my three children. At ages 11, 8, and 4, the days are a hodgepodge of activities to allow them relaxing time at home with each other and some physical activity each day. No matter what their summer plans hold (sleepaway camp for 2 of them later this summer), I always make sure they each have a stack of books they are excited to read. Each night they go up to their rooms for at least 30 minutes before bedtime to read.

Yesterday we took a trip to my favorite independent bookstore. The tiny, jam-packed store has many employees who know and love books working there (all women, it seems). The children’s section is brimming with wonderful books for all ages. My favorite thing to do is bring the older children there and let them chat with a bookseller, telling what they’ve just read and whether they liked it or not. The clerks then can make suggestions about what the kids might like to buy/read next.

When we walked in it was apparent my favorite person was not there to help us. Another woman offered, and off we went to the back room. “What have you just read that you liked?” she asked my 11 year-old daughter. “Elsewhere,” (by Gabrielle Zevin) she answered. The woman immediately snapped, “That’s too old for you. It has death in it,” she said. She looked at me quizzically, silently chastising me for my daughter’s book choice.

“I don’t mind that she reads about death,” I said.

“I loved that book… it was so good!” Paige implored.

“It’s not appropriate for a 7th grader,” the woman persisted.

“I think it’s how the subject is handled,” I said. “We talk openly about death and illness in our house, and my daughter is obviously comfortable reading about it,” I pushed.

The subject was over. She was not going to recommend any books that had to do with the death of a teenager or what happens to that character after she dies. And so, she moved on to other books and topics. Eventually, we found a lovely stack for Paige to dive into.

As soon as we left I talked to Paige about what had happened: how the bookseller had steered her away from reading about death and pushed her to “lighter fare.” I told her that I disagreed with this tactic, and fundamentally think it reinforces a fear of death and discomfort with talking about the subject.

While I believe that a teenager’s obsession with death can be a signal of some larger emotional problem, I do not think that reading novels where the main character dies is inherently a bad idea for a mature reader. After all, so many of even young children’s favorite characters in television and movies have absent/dead parents; Bambi, Max and Ruby, and countless others have significant adults missing from their lives.

I don’t believe in forcing children to deal with the topic of death in reading until they are ready. I do believe parents are the best arbiters of what information and topics are appropriate for their children. But if a child is comfortable in reading books where a character dies, I believe it’s healthy for the child to do so. As a springboard for an honest conversation about death, it can even be extremely useful in beginning to have conversations at home about it.

Paige’s grandmother was killed instantly in a car crash in the fall of 2009. She learned that the death of a loved one can greet us at any time, whether we are prepared for it or not. By trying to steer my mature child away from the topic, the salesperson contributed to the emotional shielding that makes death a topic that so many individuals (including children) have difficulty thinking and talking about.

July 3rd, 2011 §

Katherine Rosman’s piece “Why Friends Help Strengthen a Marriage” in this week’s Wall Street Journal is an insightful look at some ways in which friendships serve as additional support to the ever-challenging marital relationship. Noting that modern times have uprooted many from the anchor of their families, Rosman identifies that friends have become our “family of choice.”

Making friends with other couples is important, not only for practical and social reasons but also because they strengthen our own marriages. Rosman explains, “[A group of friends and I] all agreed that friends help you gather perspective on your relationship to your spouse: When you’re inside a marriage, it’s easy to focus on the points of friction and the minutiae of daily life.” Therefore, friends serve as a buffer, a release valve to ease tension.

As I was reading, however, I began to think of ways in which the opposite could be true. (I should note that I agree with everything Rosman says. Many/most of our own Saturday nights are busy with dinner plans with friends, people my husband and I both enjoy being with. I think it’s not easy to find couples where all four individuals truly enjoy each other’s company. Clarke and I treasure these friendships and really enjoy spending time with the people we care about. I do think it helps our marriage to be with other couples and to see how others interact. The “perspective” concept is vital.)

Here is a dynamic where I think the opposite could be true; that is, friendships with other couples could undermine the marriage:

You go out with couple A and see how they interact. Perhaps one spouse speaks really nicely to the other, compliments him/her in front of others. Or at dinner one spouse doesn’t talk too much and gives the other time to talk. One prompts the other with things like “Tell that story… I love when you tell it. It’s so funny.” Couple A spends time together, helps each other, and/or travels together. While they aren’t perfect as a couple, (who is) they are generally respectful and happy.

Now, Couple B sees this relationship. One person thinks, “Wait a second. Our marriage isn’t like that. Is that what it could be like? Why doesn’t my husband/wife talk about me that way or help me out. Maybe I could do better? Or I would rather be alone than be treated like this if I see some other people have these types of warm and supportive relationships?”

Suddenly, there is a comparison, a reference point. It is precisely this comparison component of friendship which can often be destructive. You might do the comparison on your own, or in a one-on-one chat with a friend (“How does it work in your marriage?”)

Besides comparison, another potential wedge can be introduced into a marriage with critique. Most often, we just need friends to listen. However, sometimes we ask for or they feel compelled to offer opinions, advice, and criticism. In our loyalty and love for our friends we may advise them “you know, your partner doesn’t treat you as well as s/he should.” What we take as normal, tolerable, average, a friend may plant the seed of doubt. In an effort to be supportive they may be “bashing” the spouse. “You could do better,” may be proffered.

I think Rosman’s scenario works but until a tipping point. When all of the couples are happy, (or at least have a similar sense of dissatisfaction) and the disagreements in the marriage don’t escalate, the friendships serve as buffers, releases for some of the frustrations that inevitably accompany two people in a long-term relationship. However, the critique and comparison can ultimately cause trouble. The tolerance for frustration may change as the number of years of marriage increase.

Finally, what happens if one of the couples eventually splits? Not only does that breakdown affect the dynamic of the foursome, (couples will be forced to “pick sides”) but it also serves as an example of how marriage can go awry. “If it can happen to them it can happen to us” may be a question difficult to dislodge. If comparison results in the opinion that their marriage was as happy as your own, the implications for your own long term success may eventually be called into question as the years go by and more and more couples split.

Comparison, critique, and divorce are three ways in which friendships may undermine our own marriages.

I really enjoyed reading Rosman’s piece; once again she has brought a fascinating topic to the page, one that many of us deal with in our daily lives.

July 1st, 2011 §

Okay, so today’s post is something totally different. We’re going to play, “What would you do?”

Clarke came home early for the holiday weekend. As he walked in the door the phone was ringing. I answered it and it was the local taxi company. The man on the phone said he had Clarke’s wallet and told me where we could pick it up. Clarke went back to the train station and retrieved his wallet. Later tonight I asked if he’d tipped the man when he picked it up… in essence giving him a finder’s reward. Clarke said the man hadn’t actually found the wallet; a third person had turned it in. Had the man been the one to find the wallet, he would have given him a reward, he says.

“But the taxi man still could have kept it and not called you,” I said. I thought he deserved a reward, or at least the offer of one. Taxi man could have refused if he felt that doing the right thing was its own reward.

I think that it’s nice to acknowledge that not only did the man did a nice and honest thing, but he also saved Clarke time and money by rescuing his wallet, credit cards, and cash.

What do you think? Would you have actually offered a reward when you picked up the wallet? Remember, the man Clarke picked the wallet up from was NOT the man who actually found it and turned it in, just the one who made the call.

June 17th, 2011 §

I wrote this in 2009 for my father in honor of his 70th birthday.

I am turning forty, and I still call my father Daddy sometimes.

And when I do, my voice still catches in my throat.

I’m still his little girl.

I always will be.

When I found out I was pregnant with Paige, I remember Clarke saying,

“One of the great things about having a daughter is that she will always stay my little girl.”

He knew this from watching me with my father.

My father is strong, unflappable, and focused–

Things you’d like from a heart surgeon.

Daily in the operating room I know my father displayed strength under pressure. He had to.

But the greatest demonstration of this characteristic came not in his professional life, but in his personal life when his two girls—my mother and I — needed him.

In 2004 my mom was diagnosed with cancer.

Three years later so was I.

I am often asked if my dad took control of my medical care– if he took charge and told me what to do.

Those people obviously don’t know me very well.

After all, I am my father’s daughter.

Nobody tells me what to do.

Not even my father.

That’s how I knew I had earned his respect.

He didn’t take charge.

He met each of my surgeons one time.

He knew immediately I’d chosen well.

While he wanted to know every detail,

It was because he loved me, not because he questioned me.

He trusted me.

Finally I knew I had graduated.

Grasshopper had grown up.

He has always been my teacher.

I have always been his student.

Life with him has been a master class.

He was a tough teacher.

He brought out the best in this student.

That’s what a good teacher does.

He doesn’t ask.

You just know.

You want to do your best.

You want to impress him.

You want him to take notice.

You want to earn his respect.

It’s taken forty years,

But I finally feel I’ve earned it.

It wasn’t in school.

Or with my grades.

Or with a job.

Or by getting into a certain college.

It was, instead, in the school of life.

The way I live each day.

The way I move through the world.

The way I raise my children.

The people they are becoming.

The home I have made,

The challenges I have encountered.

And the tools I have used to meet them.

I learned these life lessons from both my parents.

A girl could have no better teachers.

A thank you to my parents.

You are my supporters,

My teachers,

My friends.

Mom and Dad:

Eternal gratitude.

I love you.

June 6th, 2011 §

The rest of my family is coming back today. After a week in Jackson Hole, Clarke and Paige and Colin will return tonight, just in time for Colin’s 7th birthday tomorrow.

The refrigerator has been really empty this week. With just a 2-year old and me, it doesn’t take much to keep us fed. So I took the opportunity this morning to clean out the refrigerator and freezer– really clean them. Take everything out, throw away all the junk, the ice cream that now is just ice crystals. I tossed all of those “placeholders” that you never eat, they just take up room.

As I sprayed a wonderful new lemon verbena spray on the glass shelves, I start contemplating this week. The last seven days were my week to recover from surgery (an oophorectomy), to get stronger, to close out my year. I know I made the right decision not to join my family in Wyoming this year. It’s been a reflective time, a time for my soul to be quiet and heal. I think it’s done that a little. I think another week might help. I’ve loved my one-on-one time with Tristan; we have a nice little routine going, and I feel like he’s grown up this week.

But as the new year starts, of course, we are pushed to reflect on ourselves, to make ourselves better in the next 365 days. We reflexively reflect on whether we’ve kept any of those elusive resolutions from the previous year. December 31st is supposed to bring “closure.” In the arbitrary distinction between one year and the next (after all, why is there really a difference between the last day of 2008 and the first of 2009 any more so than any other passage of midnight on any other day of the year), we are pushed to wipe the slate clean and start anew. As I cleaned the house this week, purging old canned goods, papers, clothing, and sprucing up the house I found I was instinctively doing this: “Out with the old, in with the new.”

This annual rehabilitation, then, is supposed to be psychological and physical.

Most of our resolutions are about ways we want to be better, inside and out: concentrating on the new and gaining closure on the past.

One of my dearest friends wrote to me in an email last week, “And yet, you can no more gain ‘closure’ on life-altering events than you can erase moments from your memory.” I read that sentence many times. It is beautiful, and true.

I remember well when my friend Alex’s father died of cancer almost 10 years ago. She was so busy with all of the things that needed to be done, the arrangements that needed to be made, and taking care of her mother who needed constant attention and support. I remember wondering when she was going to grieve. I worried that his death, and his absence from her life, would fester and haunt her.

As I scrubbed the refrigerator shelves this morning I realized that you never grieve the way you think you should.

No one really just sits alone and thinks about the tragedies that befall them.

It’s too painful, too powerful to take that in as one big gulp.

Instead, what we do is weave it into the tapestry of our consciousness.

We make it part of our daily life, quiet, but present.

Maybe at this time of year we reflect more than usual, and maybe that’s why the holidays are painful as we take stock of what we’ve lost during the year and what we’ve gained.

Where that balance lands says a lot.

A year ago I thought surely 2008 would be better than 2007. It really didn’t turn out that way. But I am doggedly optimistic even when I’ve been been proven wrong so many times. I do not believe that there is a “justice meter” in the universe that is going to now dump things on someone else and leave me alone for a year. But maybe as my own tapestry of consciousness keeps getting woven, it will be stronger and more resilient to keep me going this year.

At least I’m starting with a clean refrigerator.

originally written January 2, 2009. Modified June 6, 2011

May 30th, 2011 §

Each year my letter to troops stationed overseas is similar. Each year I question whether I should write something new, if it’s “cheating” to say the same thing. In the end I realize that thank you never gets old, it never needs to be re-written. Thank you doesn’t have an expiration date.

This year we went to buy items for the care package drive sponsored by the Darien Little League. Volunteers collect supplies including toiletries, non-perishable food, and games and send them to soldiers far from home. While the supplies are important, and more than 500 boxes will go, the most important items sent are the letters. The letter I sent this year has the same theme: bravery– chance or choice?

May 28, 2011

Dear Servicemen/women,

My family and I are sending you some supplies on this Memorial Day Weekend. We want you to know that we have not forgotten you or the sacrifice you are making every day to be away from your own families and in harm’s way. It’s not much, but perhaps knowing you are in our hearts and minds will help.

Four years ago I was diagnosed with cancer (I am now in remission). When I was going through treatment, people called me brave. I didn’t deserve it. “Brave” was not a word you used about someone like me. I had gotten cancer by chance and I dealt with it, the best I could.

But soldiers? You are brave. You have a choice—you put your lives on the line after making a conscious decision to do so. You know the danger and you do it anyway. To me, that is true bravery, true heroism.

It feels good to say it, to confess it. I have been called a word I haven’t earned.

Seeing danger and making the choice to proceed anyway is precisely how I define bravery. We all find ways to deal with the fear of death. We know the uncertainty that lies ahead. We see the bravery in others before we will see it in ourselves.

What underlies bravery: chance or choice? Can both? Are we just hesitant to see the quality in ourselves? Are we just modest? Do we just act the way we need to, to get the job done?

I think when you choose to throw your hat in the ring, that choice counts for something. That makes you brave. That’s what makes soldiers heroes. Happy Memorial Day to you. And thank you for your continued service to our country.

May 25th, 2011 §

A few months ago I asked my mother to share some thoughts on the difference between guilt and regret (A Psychologist’s Perspective on Guilt vs Regret, February 7, 2011). That post quickly became one of my most-read pieces. When I knew my mom was coming to visit this past weekend I asked, via Twitter, if anyone had any questions they wanted me to ask her.

One reader wrote:

My mom passed away six years ago, when I was 24, after a five-year battle with cancer. I’m getting married in a few months and I’m finding two things difficult: 1) going through a big life change, and the actual planning of the event, is making her loss feel much more at the forefront than I expected; 2) I’m struggling with marrying someone who didn’t know my mother and doesn’t understand (and honestly, not sure how he can, not being there) my grief.

My questions are: how do you help the new people in your life know the person you lost and understand the depth of your grief? And how do you deal with the new kind of grief that comes with entering a new phase of life?

……………………………………..

My mother, Dr. Rita Bonchek, spent her career as a psychologist specializing in grief, loss, death, and dying. She had some thoughts on the subject. I decided to add my own take on it; that perspective appears after hers.

……………………………………….

Dr. Rita Bonchek writes:

In American society, the topic of death causes great discomfort so people do not think about or discuss the subject. When the death of a loved one occurs, the bereaved are often encouraged to put the occurrence in the past. Freud felt that the mourner needed to ” let go” in order to move on. However, when Freud experienced the death of his favorite grand-child, he often expressed with great sadness that he would never get over the loss.

What is not appreciated about the death of a loved one is that “Death ends a life but it doesn’t end a relationship that lives on in the mind of the survivor.” Some studies have shown that mourners hold onto the relationship with the deceased with no notable ill effects.

A childhood death of a parent can be a devastating event. How the child grieves is extremely individual and based on the child’s age when the parent died, the cause of the loss, the quality of the parent-child relationship prior to the death, and the support system available both at the time of the loss and afterwards. If a surviving parent removes all items and pictures of the deceased and does not talk about him or her, the child is denied the grieving process. The secrecy and the inability to have a shared grieving between the child and family that shares the loss is a travesty.

The mourning for a mother never really ends. Even after many years while there may not be active grieving, there are what one child called “mommy-missing feelings.” And what does a mother provide for a daughter: support, advice, a significant person who can help and validate the child during development. No one else is so uniquely important to the child as a mother who helps her to form an image of herself. With this self-image, a daughter is helped to determine how to interact with the world and the people in this world. A daughter’s feelings, thoughts, hopes, desires and attitudes are influenced by a mother. But this mother does not have to be the mother who existed in real life but who is a mother who exists in the daughter’s heart and mind. This is a mother who is carried within a daughter forever.

When a mother-daughter relationship has been strong and positive, a mother loves a child in a very intense and special way. A daughter will miss a mother’s protectiveness, loyalty, encouragement, praise, warmth, and, as the daughter becomes a woman, an adult-to-adult friendship. There are special times in the developing daughter’s life in which the absence of a loving person is painful: graduation, confirmation, Bar/Bas Mitzvah, a wedding celebration, the birth of a child, etc. This is when the wound is re-opened.

Who the daughter was when her mother died is not who she was after the painful event. Every death of a loved one changes us and causes us to re-grieve the loss of other loved ones. Hope Edelman, in her book Motherless Daughters encourages women to acknowledge, understand and learn from the changes that occurred as a result of the early loss of a mother. It can take years. With reflection and understanding of what was lost when her mother died, a daughter can, with greater sensitivity, become her own role model as she creates a strong family and friend network of her own.

…………………………….

I had the following thoughts:

Even though the death was six years ago, it happened to you at a time before marriage and/or motherhood. While not relevant to all women, these are often defining events in their lives. While you had your mother for your childhood, oftentimes daughters do not fully appreciate their mothers until they become wives and mothers themselves. When you no longer have a mother to admit “now I understand what you meant” or “I’m sorry for how I behaved as a child” it can feel that there is unresolved business at hand. Not being able to ask, “Is this how you felt on your wedding day?” or “What was your day like?” is difficult.

Of course, a wedding is one of these events that is tied to family. How can you possibly explain the ways in which these occasions make you miss your mother? As my mom said, it’s not just the relationship you had that you grieve, it’s the relationship you could be having now. There is no way to fill that void, no one can fill that space. I think that incorporating your mother and her memory into your ceremony may provide a way for her to be remembered and present during your wedding. Because your fiance did not know her, he will not miss her in this event. You will, however, as some of the guests at your wedding will too.

It’s a common misconception that talking about your mother or acknowledging her absence will “make people sad.” On the contrary, I believe that talking about her and her absence is appropriate. One way I think this is appropriate is to mention her in the wedding program and/or light a candle during a portion of the ceremony that names those who are “special to us but not here to share this day.” I have seen an acknowledgement of special friends and family who are deceased but remembered on this special day. A paragraph, properly worded, could mention your mother’s role in raising you, making you who you are today, and how you wish she were here to share this occasion. Similarly, wearing a piece of her jewelry or clothing (like a veil) or carrying her favorite flower in your bouquet might help you feel closer to her on the actual day.

Grief sneaks up on you when you least expect it; the reflexive reach for the phone is a hard habit to break. Both happy and sad events can make you miss loved ones. Every little thing reminds you of your loved one, the things you did and the things you had yet to do. You grieve the relationship you lost and the one you had yet to build. The relationship was truncated, and that cannot be fully appreciated by someone who has not experienced it.

I don’t know if you have shared a lot about your mother with your fiance, but I think it’s important to do so before you get married. I think it’s important to write about her and talk about her with him. He’ll never be able to understand fully, and he’ll never miss her since he didn’t know her as you did. But he does need to understand how important she is to you now even though she’s no longer alive. That may not be intuitive– although your mother died six years ago she is still a very important part of your life.

It’s important to say that not all of the memories surrounding your wedding would necessarily be happy; after all, weddings can be prime opportunities for mothers and daughters to clash. However, the pivotal moments of walking down the aisle, first dance, photographs, and so on can be especially difficult.

Sometimes when we grieve we don’t know exactly what we need, and in the end, no one can provide the “fix” for us — that could only happen if our loved one came back. Realizing that you don’t really know what you need all the time as you go through this is important, too. Something your fiance says might be incredibly aggravating one minute (a reminder that “he just doesn’t understand”) but other times the same thing may strike you as supportive. He’s in a tough situation because he’s trying to support the woman he loves on a day that is supposed to be one of the happiest days of your lives together. However, it has a component of pain involved for you. He needs to accept that dialectic and not try to gloss over or erase the pain that will accompany all of the happy days you will have together. He needs to know that grief will be a part of every happy event you will have in the future because your mother is not there to share it. The sooner he can accept that truth, the better it will be for both of you, I think.

I hope that some of these thoughts will help you in the months leading up to your wedding and that you can find a way to incorporate your mother’s memory into your ceremony. I know she will be in your heart and on your mind.

May 18th, 2011 §

A few weeks ago I was talking with a friend about our blogs. She said that she never writes about her husband; some readers didn’t even know she was married. I don’t directly write about my husband Clarke often. I’ve written endlessly about his mother Barbara’s sudden death in a car crash in 2009 (if you want to read more about her, please click on the tag “Barbara” on the lower right of the page) but not about Clarke. Clarke is private, and I respect the fact that he doesn’t want to write or discuss topics that I do.

Clarke wrote a piece that I treasure. In 2009 he nominated me as a “Brave Chick” for a website that celebrated women who had tackled adversity (www.onebravechick.com). The interesting thing to me as I re-read the essay now is how much more has happened since then. We’ve had many medical and emotional challenges since this letter was written. I like to think that the seeds of strength were sown during some of these experiences.

I am re-posting this today not to celebrate myself, but rather to celebrate my husband. We are a team in this thing called life and I couldn’t do it without him. I hope I will get him back here on the blog sometime to write about some more of the issues we have dealt with; I think hearing it from his point of view might be helpful for some readers. But for now I will let his words sing, and hopefully honor him by doing so.

…………………………………..

“The bravest sight in the world is to see a great man (or woman) struggling against adversity.”

-Seneca

“Let us do our duty, in our shop in our kitchen, in the market, the street, the office, the school, the home, just as faithfully as if we stood in the front rank of some great battle, and knew that victory for mankind depends on our bravery, strength, and skill. When we do that, the humblest of us will be serving in that great army which achieves the welfare of the world”

-William Makepeace Thackeray

My wife Lisa and I met for the very first time at the George Foreman / Evander Holyfield fight in the spring of 1991 when, in a scene straight out of Rocky, a forty-two year old Foreman went the distance with the undefeated Holyfield. We met again at a Halloween party later that year and began dating. We got engaged in 1995 and married in the summer of the 1997. Over the course of our 18 years together and in particular the last three, it has become clear to me that my wife possesses more than her share of courage.

As with any 18 year period we have had our ups and downs together but mostly it has been up. We have three beautiful and intelligent children, loving and supportive families and great friends.

In the grand scheme of things, our life together was pretty smooth which is why I think we were completely unprepared for what the last three years have brought us. In August of 2006 we learned that our five month old baby boy was born with a condition that required immediate open heart surgery. He also had complex problems with his cervical vertebrae and the muscles of his hands that would require a significant ongoing investment of time and energy in medical care and therapy.

Since Lisa is at home with the kids when I’m at work, the day-to-day heavy lifting of running the house and managing the often crazy logistics of our lives naturally fall to her. In addition, because she is the medically savvy one in our family (her father is a surgeon and her mother is a psychologist), Lisa ended up quarterbacking and supervising Tristan’s care which included (and still does include to some extent) coordinating treatment with four or five different specialists (neurologists, pulmonary specialists, pediatric cardiothoracic and orthopedic surgeons, etc.) in three different cities. Juggling all of those competing priorities was extremely challenging and time-consuming. It seemed like fate was piling on hardship in January of 2007 when Lisa was diagnosed with Stage II breast cancer.

Lisa spent much of 2007 aggressively treating her cancer with a double mastectomy and chemotherapy. I’m sure many women who read your website are acquainted with the harsh reality of how tough a cancer treatment regimen can be on one’s body and, just as importantly, one’s psyche. I must confess that I wasn’t really prepared for what was to follow. Like many things, cancer treatment seems much simpler in the abstract or on television than in the messy reality of real life. It is a process where you are forced to make life-changing and often heartbreaking decisions while in possession of only limited information all the while dealing with the physical, mental, and emotional side effects of disease itself and the treatment. If adversity is the test by which character is revealed then I’m proud to say that my bride has passed her personal test with flying colors.

At least by the romanticized ideals of literature or history you don’t get to see real bravery very often when you live in Darien, Connecticut (braving the long lines at the local Starbucks doesn’t really count). However, there was something quietly heroic in how Lisa handled the myriad of issues she was dealing with in a thoughtful and calm (with some exceptions) manner all the while taking care of the thousand little details that go along with being a mom to a young family. No matter how much personal pain she was in, the kids’ lunches got made, their homework got done, their boo-boos got kissed, and their very real fears addressed and soothed even on the very worst days. Tending to young kids isn’t easy on your best day but being able to do so and face the world in the midst of cancer and chemo and all that implies is something else altogether.

Looking back, the amazing thing to me is how little impact the whole period had on our children; that speaks to how much of her energy and force of will Lisa put into ensuring that that was the case. We had lots of help from our families and our amazing group of friends, but at the center was Lisa getting up each day and doing her best to move forward with grace and determination (kind of like a 42 year-old George Foreman coming out of his corner, taking his licks and getting in some good shots of his own). In my book, that is all any of us can really expect of ourselves and defines what bravery is all about. When my test comes, I hope I do as well and face up to it with as much strength as Lisa did.

A friend whose wife had just gone through the breast cancer experience told me when I learned about Lisa’s diagnosis “the thing about breast cancer (pardon another tortured sports metaphor) is that you never get to spike the ball in the end zone and say you are done. There is always something else.” I thought I understood what he was saying at the time, but I appreciate it much more now. Although chemo ended in the summer of 2007 and her breast reconstruction finished shortly thereafter, Lisa has been dealing with the often frustrating regimen of drugs and side effects that come along with being a cancer survivor. While things are certainly better than they were, it has been a constant challenge and adjustment for both of us.

As I said earlier, one of the most difficult things about having cancer, even a cancer that is as common and well known as breast cancer, is that you really don’t have any idea what is ahead of you as either a patient or a spouse when you begin the process. There are reams of data and academic studies available but despite that fact, it is difficult to distill and digest all of that into a coherent picture as to what you as an individual (or the spouse of one) will experience.

As part of her life as a cancer survivor, Lisa has taken it upon herself to make understanding the long road of treatment, recovery, and being your own best advocate a little easier for women who will face the same challenges she did. She spends hours and hours speaking to women in our community who are just beginning the process about what she has been through in the hopes it will help them be prepared. As an extension of those conversations she began writing (and later blogging) about her experiences and feelings about cancer and posting them on the web. She sometimes writes clinically about the nitty-gritty medical realities of treatment and recovery which are based on her personal experiences, extensive research of the available medical literature, and her own conversations with her doctors.

Other times she examines the darker, emotional, frustrating, and deeply personal places that being a cancer survivor can sometimes bring you as young woman and a young mom. Her writing is often beautiful and poetic and is always thoughtful and enlightening. She puts it all “out there” for public scrutiny. She posts regularly under her own name to help her fellow women (our moms and sisters and daughters) understand and deal with a path that all too many of them will walk down at some point in their lives. I believe this is noble and selfless and courageous.

So as a very small and modest way of acknowledging her daily efforts and recognizing her achievements, I would like to nominate Lisa Adams (age 39), loving wife, wonderful mother, caring friend, talented writer, and strong cancer survivor to be a featured brave chick. I would invite those members of your community who are interested to check out her writing at lisabadams.com.

Thanks for your time and dedication to Brave Chicks everywhere.

Clarke Adams

July 7, 2009

May 13th, 2011 §

One of the defining features of childhood is innocence.

As children we don’t realize that things change. We think the way that things are when we go to bed at night is the way they will be in the morning. We put the bookmark in our lives and expect everything to be the same when we return to it.

Of course, as we grow we realize that’s not true.

That it can’t be true.

That’s not how things happen.

That’s not the way the world works.

And what do we say when someone still believes it? We say he is being childish.

Oftentimes I wish I could retreat to childhood. Not because of how my childhood was, but because I want to recapture that mindset, the one that says that everything is going to be alright. When people tell me “everything is going to be fine” I snort. I recoil. I don’t believe them.

It’s not always going to be alright.

Sometimes it is. Sometimes it isn’t.

But the road you must take to figure it out might break you before you ever find out for sure.

May 8th, 2011 §

I can do better, but I have done my best so far.

I’m not the fun mom, but I’ve taught my children big lessons in their young lives.

I try to be a good wife, mother, daughter, friend.

I try to inhabit the womanly roles even when I don’t always feel feminine.

I spend a lot of time inside my head,

twisting, pulling, ruminating.

It doesn’t mean I’m sad. It means I’m thinking.

I’ve made mistakes,

I regret some of them.

But my children are not those mistakes: they are my legacies.

I look at them and wonder how it can be that Clarke and I have created three people. Literally given them life.

It is a joy for a mother to see her children grow,

learn to inhabit the space they take in the world,

learn to own that property.

It’s as if children need to learn the size of their bodies– the breadth of their being– in order to go out into the world and participate in it.

I love watching this process unfold.

I can do better in the future, but I have done my best so far to mother them.

And really, that’s all anyone can ask.

April 30th, 2011 §

What does it mean to “be an inspiration”? A few people have said that to me recently: I am an inspiration. At first I laugh. I guess I’m an inspiration because I’m still alive. Maybe that’s enough.

What’s inspirational about me? Trust me, I’m not searching for platitudes here. I’m trying to get at “what makes someone an inspiration” and why do people think I and so many other breast cancer survivors qualify? There’s definitely more than one day’s blog in this question.

Is it being a mother and worrying about your children more than yourself? No. That’s what every mother does.

Is it summoning strength to confront chemo when it’s your greatest fear?

Is it putting a smile on your face when you are crumbling inside?

Is it speaking the words, “I have cancer” to your children, your friends, your husband, your parents, your in-laws, your brother, and all of the people in your life enough times that eventually it starts to sound normal?

Is “inspirational” when you offer to show your post-mastectomy body to women so that they will know the results just aren’t as scary as they are thinking they will be?

Is it answering everything and anything people want to know?

Is it putting words and feelings in black on white?

The essence of inspiration is being strong.

When you least want to be.

When you are faking it.

Strength.

When you lack it.

When you have to dig deep for it.

When your kids need dinner and you want to vomit from the chemo.

When you are too weak to climb the stairs.

And you don’t think you can get through another day.

Or hour.

Or minute.

Or second.

And you just want the pain to end.

Somehow.

Some way.

Any way.

Just have it go away.

When your pride is gone.

Dignity is gone.

All of it.

Being inspirational means being tough.

It means feeling rotten but not wanting others to.

It means wanting to put others at ease with how you are doing.

It means being a lightning rod for everything bad.

A catalyst for everything good.

A spark.

A resource.

A friend.

A wife.

A lover.

A mother.

A daughter.

It means telling your parents you feel okay when you don’t.

A little fib so they will go home and get some rest for the week.

Take some time off for themselves before they come back in 8 days and do it all over again.

A break so they don’t have to see their little girl suffer anymore

Because 6 days in a row is enough.

For anyone.

Because looking good makes others feel better about how you are doing.

So you put makeup on.

And dress well.

And put a big smile on your face.

So they will think you are feeling good.

And when you switch the topic of conversation, they will go along with it–