We gather friends like seashells throughout our lives, tucking the treasures away to take with us as we walk. At different times, we appreciate different qualities of those friends; characteristics that initially attract us to someone may later be a source of discomfort. Some friendships last entire lifetimes, others are brief but intense. Friendship is an art form, one we must learn and practice daily.

I recently read Lindsey Mead’s post about friendships made during life transitions. She writes, in part: “It strikes me that it is not an accident that our truest and most lasting friendships are forged during times of life transition; we are closest to those who have shared experiences that changed who we are. Whether it was childhood, college, or becoming mothers, this is true for me.”

I’ve thought about this for weeks because while I absolutely understand what she is talking about (and do have some friends like this), I’ve also seen many of those friendships fall by the wayside. I have written before about the ways cancer and friendship sometimes don’t mix. There are friends who just can’t deal with a friend’s illness and/or death of a family member and they just disappear. In contrast, there are friends who seem to thrive on helping when there is a crisis underway.

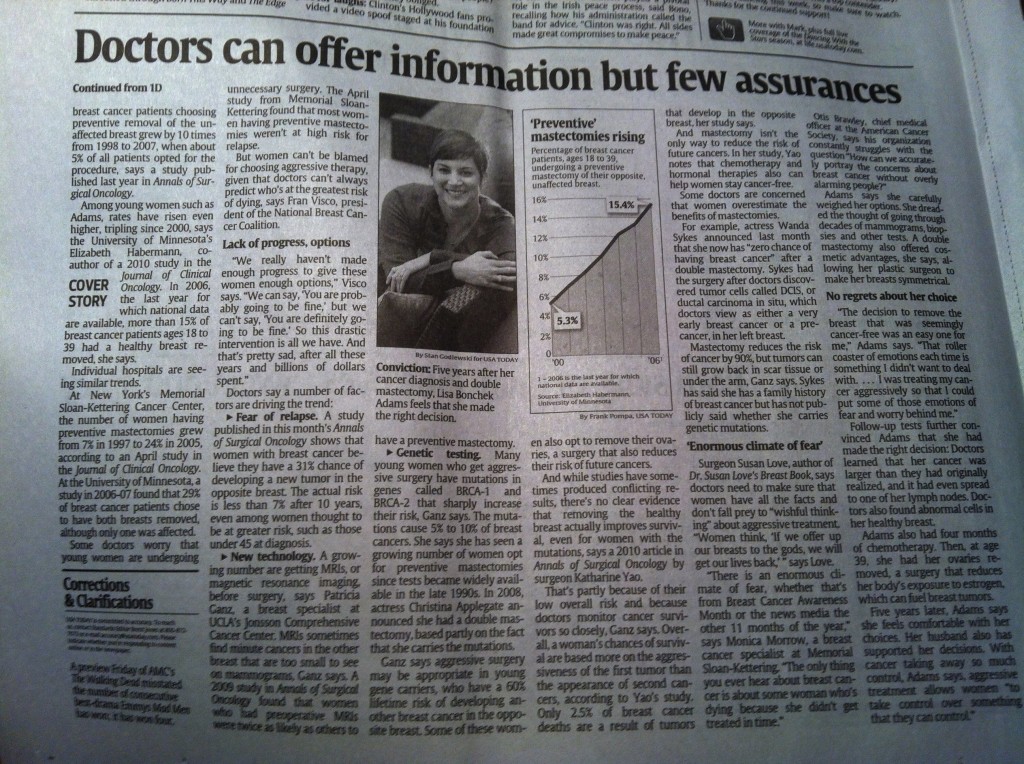

When I was diagnosed with breast cancer at 37 I did not have any friends who had already had the disease. One of my closest friends has a son who had experienced leukemia twice and received a bone marrow transplant from his sister that saved his life. I talked with her a lot, not only because she had some sense of the fears I had but also just because she is my friend and a great listener. While I treasured that connection, though, I didn’t know anyone who had recently had a double mastectomy, chemotherapy, or needed to figure out how to balance those treatments with caring for three young children. My diagnosis preceded my involvement with Facebook and Twitter; social media would have greatly changed my experience with cancer.

I didn’t like support groups; they just weren’t right for me. Instead, I found myself talking to and finding support from a few women who used some of the same surgeons I did. We’d see each other in the waiting room at the plastic surgeon’s office when we went for weekly “fills” to add saline to the tissue expanders in our chest that were stretching the skin and making space for the implants some of us chose to receive. During chemo, nurses would often try to put younger patients in the same semi-private chemo room so they could meet and pass along wisdom and support.

Not every interaction I had led me to a friendship, of course. Sometimes in stressful situations we just need someone to help get us through. Like the stranger in the seat next to you during a turbulent airplane ride who chats with you and passes the nervous minutes, we rely on strangers to steady us when we wobble. We look for cues that everything is okay, that our experience is in the range of what might be expected.

But as my chemo and surgeries and constant doctor appointments waned, there was more room for “the rest of our lives” in the conversations I was having. One woman and I became quite close; we’d meet for coffee and spend hours talking about cancer, its effect on us, our children, our spouses. We were different kinds of people, though, in dealing with our similar cancer diagnoses. As time went on, it became more and more apparent. For example, she didn’t want to share as much information with her children about her cancer as I did. She turned to controlling food as a way to deal with her fears of a recurrence; she felt she would be immune from a recurrence if only she only ate certain foods. She wanted to train to be a Rekei healer. Eventually, though, it was our disparate attitudes about cancer that drove a wedge between us. She felt it was important to always put a sunny face on cancer; she felt it was necessary to find the joy in it. She had a “head painting party” when she went bald from chemo. She had her daughters paint her head with designs and words. She collected positive sayings into a little book that extolled the virtues of positive thinking as a key to remission success.

I could be her friend and listen but I could not agree with what she believed. The thought of someone placing their hands over my skin but not touching it and transferring energy to me (Reiki) did not work for me. I didn’t believe that food was key to avoiding cancer (after all, I had friends who had been vegetarians before they got cancer; if food were the simple key to avoiding cancer we’d have figured that one out by now, I thought). I felt control of food was a grief reaction, a way to manage fear in an uncertain world. That difference alone would not have come between us, though. I think it was the “positive thinking is the key” that I think was the biggest stumbling block. We just fundamentally differed about how to approach this disease that dominated that period in our lives.

I was strong, determined, motivated. I researched the available options and discussed them with my medical team. I pushed back when they suggested certain treatment options. I was a participant in my treatment plan. But I also felt that this thing called cancer SUCKS. And it was okay to say that. It was okay to have a bad day, or hate shaving my head. I didn’t have to have a head painting party and rejoice in the experience of going bald from chemo. It was okay for me to get halfway through shaving my own head in my garage on the morning of my second chemo and tearfully ask my father to help me finish because I couldn’t get it all. It was okay to cry, to scream, to pout for a bit. Then I picked myself up and moved on. That’s what worked for me.

Every time I got a piece of bad news or felt overwhelmed after a doctor’s appointment I allowed myself 24 hours to recover. That day I could complain, feel the injustice of it all, just react. But the next morning: it was time to get on with it. Those negative feelings were important to me. They were real. They were how I felt. And having someone constantly saying that I should only think positive rubbed me the wrong way. It was, to me, “pinkwashing”: making breast cancer seem less awful than it often is. If the only things I expressed were how “cancer is a gift” and I “had to find the beauty in it” (as she did) that denied a very real truth to me: cancer had fundamentally changed my life and those around me, and those changes weren’t always positive.

It didn’t mean there weren’t experiences or people or lessons that I appreciated. It didn’t mean I didn’t want to emerge a wiser person for having gone through it. But “cancer is a gift”? No way. I saw blogs and books where survivors wrote, “Cancer is the best thing to happen to me.” I will never say those words. I think of all of the people in the world who live with cancer every day, whose lives will be cut short by it, who have lost people they love to the disease. In my mind it diminishes their deaths and diminished quality of life to say their disease is a gift. I will not say that cancer was the best thing to happen to me.

My friend and I just sort of fell out of touch, though we have talked a few times in the last few years. We have only warm feelings for each other and wish each other good health and happiness. But we aren’t close. And what that tells me is that cancer is a part of life. You can’t make a relationship work just because you have the same disease. We have different kinds of friends for different reasons. Some we love them because they are “just like us” and share common interests or senses of humor. Some we love them precisely because they are different– they push us in ways we are not accustomed to or expose us to interests or information we otherwise might miss. In this day and age we have Twitter friends, best friends, school friends, Facebook friends, etc. We interact with a variety of people in very different ways.

I also realize that we have different levels of patience for conflicts at different times in our lives. Maybe the differences I had with my friend about cancer wouldn’t bother me so much now. Maybe we were both raw and stressed about managing our illnesses and our families. We supported each other through the hardest times and once that period was over we just moved on in different ways. Maybe that wasn’t even what really caused our relationship to cool off in the first place; after all, we didn’t part ways on bad terms, the friendship just “fizzled.” It happens.

I realize I’m more likely to make friends in the daily grind of life, and my life is full of more people I consider friends than ever before. I have a rich network of people I like, trust, and enjoy spending time with. We are not always similar, and we don’t even have to share the same beliefs all of the time. Respect and kindness are hallmarks of friendship, and every relationship for that matter. I really enjoyed thinking about the friendships I’ve made, how I’ve made them, and which ones haven’t worked. The topic of cancer and friendship is one I will continue to write about. I treasure the friends I have. I am fortunate.

Thank you to Lindsey for planting the seed for me about this topic; she and her blog frequently push me to think, learn, and grow. I’m still ruminating on this subject… and I like that.

Link to Twitter

Link to Twitter