September 27th, 2011 §

September 29, 2010

Most of you probably read the title of this post and thought I was going to write about the guilt we may feel as parents over the course of our children’s lives when we can’t be there for every event they want us to attend or say no to things we know they might want to do.

But that’s not what I mean by “Mommy guilt.” Instead, it’s the feeling I have today because my mother is coming to visit.

I feel guilty because I have a mother who’s alive and many people I know do not.

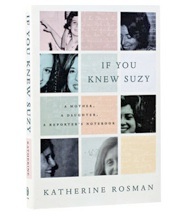

I commented on Twitter this morning that my mother was coming for a few days. Author and friend Katie Rosman tweeted back “jealous.” Katie and I actually met because of the moving book she wrote about her own mother’s death five years ago, If You Knew Suzy. I wrote a blogpost about that book; in it I shared personal feelings about having cancer and what my legacy might be for my children.

But there was more.

Katie’s mom is dead. So is my husband’s mother. So are the mothers of many of my friends. And as I go through middle age this will happen more and more. And someday it will happen to me.

Every time I drive the fifteen minutes to the Amtrak station to pick Mom up (when she and my father don’t arrive by car here together) I think about the night I drove to get her at the train station the first time she came to visit after Barbara died.

When I saw my mother step off the train that night last year I almost had to look the other way: it was like looking at the sun.

The sight of her was

so bright,

so intense,

so welcome,

so wonderful,

that I almost had to look away for a moment.

The guilt over being able to see her step off that train and into my arms again overwhelmed me.

And so, today, when I see her again, I will hold her, kiss her, hug her. I’ll hug her for an extra moment and think to myself: this is for all of you. This is for all of you who have lost your moms and can’t do this simple act anymore. A way I can honor her and you is to appreciate these times we have together because I know there are so many who would give anything to have one of these moments with their mom again.

September 16th, 2011 §

September 16 is the anniversary of the death of two women I loved: my paternal grandmother, Sara, and my mother-in-law, Barbara.

Bubbe (Yiddish for “grandmother”) died in her 80s, many years ago, after her health had begun to fail. She lived in Israel, and I did not have the opportunity to see her one last time before her death. In stark contrast, Barbara died only weeks after I last saw her, laughed with her, attended a family wedding with her. We had no earthly idea she would be killed in a car crash, of course, no time to prepare ourselves for hearing the words that rocked our world.

It was Open House at my children’s elementary school that night, and when the phone rang I didn’t recognize the voice. It was my husband’s voice, strained, hiccuping, sobbing. I didn’t understand at first; I couldn’t process what he was saying. In the same way I quizzically furrowed my brow when I sat in the basement of my daughter’s school in New York City and the principal announced on that first day as our preschoolers were upstairs, “A plane has hit the World Trade Center,” I again heard information and my brain responded with Does Not Compute.

Anticipatory grief is real. A diagnosis, a doctor’s report, an assignment to hospice– all are ways others try to prepare us for the death of our loved one. With each step, with each caution, with each added conversation we start to get our minds used to the idea that it may be the end. Like a threadbare shawl we continue to wrap ourselves in, each time we are comforted less and less by others’ words of reassurance.

When a death is sudden and unexpected, there is so much to get used to, so much to process. It is a task to make sense of the death, to integrate it into our consciousness. We must unbreak habits. I remember so clearly when my uncle Alan died, I still continued to pick up the phone again and again to share a piece of news. I had to keep reminding myself, “You can’t call him anymore.”

There are so many talks I have missed with these women. There are so many things I’ve wanted to show them, share with them. However, I am so lucky to have had them in my life for as long as I did.

September 9th, 2011 §

I drove by it thrice today: the little house with the purple awnings.

It’s on the street near my children’s school… within walking distance, in fact. It almost always has a For Rent sign out front and seems perennially in a state of slight disrepair.

Barbara used to pass the house and say, “Paige, I could rent that house. And then you and your brothers could stay with me and I could walk you to school in the morning.”

We knew she wasn’t going to rent it, but the idea of having her so close was so appealing to us all.

“Whenever the boys are giving you trouble you can just walk over here,” she’d say to Paige. “We could have sleepovers.”

Grandma’s little cottage we sometimes called it.

But then Grandma died in a car crash— almost exactly two years ago. When that happened, our dreams of seeing her often and Paige’s fantasy of having her in the little cottage died too.

And so, today — and every day when I pass the house with the purple awnings– I think of her. And miss her. And all of the memories we could be making in the little house with the purple awnings right now.

September 6th, 2011 §

The house is so quiet… for the first time ever, all three of my children are out the door before 8:00. Tristan will have half days of kindergarten for the first two weeks so the change from preschool won’t be too dramatic. And yet, somehow with his backpack on, lunch pack clipped to it, it is different. He stands at the bus stop with a bunch of other children from the street; some of them were babies when we first moved here seven years ago. I see the changes in them after the summer more easily than in my own.

These are the psychological stretch marks I’ve written about before. These are the moments you know are monumental. Growth happens in fits and starts, not with smooth, sliding grace. This shift is simultaneously sudden and gradual in its arrival; I’ve been counting the days for the last month, but still the finality of its presence takes my breath away. With Tristan it’s different, his life thus far has been a challenge in many ways (background on Tristan and his physical abnormalities here). We’ve been a team, and worked so hard together. He will continue with OT and PT and need a few modifications in the classroom. But I know he’s going to be just fine.

I’m looking forward to writing again… the last month has been busy with things mostly of the unpleasant kind. But the routine of the fall, the schedules, the calendars give me structure. And with structure comes comfort. I can get through this rocky time. I can create the life I want, the one I need. I just have to keep trying.

August 2nd, 2011 §

I thought they would always be together. I thought it would be until the end. When I look back over the things I’ve written about my parents, a constant theme is always how I can’t imagine them without each other.

And yet, this week, my mother moved into her own condo and began her life apart from my father.

Their dynamic just was not working anymore; six months shy of their 50th anniversary, they’ve decided to separate.

I’ve known for a few months, and the children know now too. In fact, as I write this, my parents are (together) spending a week with Paige and Colin as they do each summer. Nothing, even the decision to move forward apart, comes in the way of that this year.

I’m still a child. Their child.

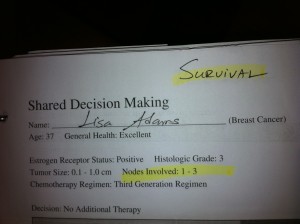

I’m learning that no matter how old you are it affects you; age is not a protective shield against the hurt that can accompany such changes. Now 42, I have two generations to consider: my parents and my children. At the moment my parents’ health is good; I’ve written before about my mother’s stage III cancer diagnosis six years ago (she is in remission). But I confess, even on their healthiest days I play the “what if” game. I feel I need to always be thinking about the future, making sure I have an escape route. Like a stewardess pointing with a flourish to an exit in the forward cabin, I need to show myself that there is always a way out, a plan should something go wrong.

Even in the face of truly excellent health we’ve learned that life can change in an instant; after all, Clarke’s mother was perfectly healthy when she was killed in a car crash almost two years ago. I did not have a “what if” mentally written for that circumstance– how could I? But I have seen the way a tragedy can change a life in a split second. I think my confidence in what the day will bring has been shaken; I no longer believe that the day shall end as it began, life bookmarked in its progress.

I love my parents dearly; I am as close to them as a child could be, I think. We laugh, we talk, we share. I wouldn’t have it any other way. But the fact we are so close means this new chapter of their lives affects me deeply. How can it not? The very foundation of home life I have know my entire life is gone. I’ve been married for fourteen years; I am not a naive child who thinks wanting to make it work is enough.

And so, I program my phone with my mother’s new contact information; she gets her own entry now. I order change-of-address cards for her, and return address labels. Information now needs to go to two places. Anecdotes about the children need to be recounted twice rather than hearing my voice echo on speakerphone in the kitchen.

I support their decision– how could I not? I want them to be happy, and to achieve this goal they must live apart. But my knowledge that it’s what is best doesn’t make the bitter pill any easier to swallow.

I know a lot about grief and loss. I know that it takes time. This loss is something I’m dealing with, and will continue to, day by day.

July 5th, 2011 §

Last summer I wrote the following piece about an upsetting interaction I had with a bookseller. It remains one of the posts that readers mention and still ask me about. The topic of children and death must be a touchy subject for most. I guess because I grew up with a mother who was a psychologist specializing in these topics I have never felt uncomfortable talking about them. Let me know what you think.

……………………………….

June 23, 2010

School is out for my three children. At ages 11, 8, and 4, the days are a hodgepodge of activities to allow them relaxing time at home with each other and some physical activity each day. No matter what their summer plans hold (sleepaway camp for 2 of them later this summer), I always make sure they each have a stack of books they are excited to read. Each night they go up to their rooms for at least 30 minutes before bedtime to read.

Yesterday we took a trip to my favorite independent bookstore. The tiny, jam-packed store has many employees who know and love books working there (all women, it seems). The children’s section is brimming with wonderful books for all ages. My favorite thing to do is bring the older children there and let them chat with a bookseller, telling what they’ve just read and whether they liked it or not. The clerks then can make suggestions about what the kids might like to buy/read next.

When we walked in it was apparent my favorite person was not there to help us. Another woman offered, and off we went to the back room. “What have you just read that you liked?” she asked my 11 year-old daughter. “Elsewhere,” (by Gabrielle Zevin) she answered. The woman immediately snapped, “That’s too old for you. It has death in it,” she said. She looked at me quizzically, silently chastising me for my daughter’s book choice.

“I don’t mind that she reads about death,” I said.

“I loved that book… it was so good!” Paige implored.

“It’s not appropriate for a 7th grader,” the woman persisted.

“I think it’s how the subject is handled,” I said. “We talk openly about death and illness in our house, and my daughter is obviously comfortable reading about it,” I pushed.

The subject was over. She was not going to recommend any books that had to do with the death of a teenager or what happens to that character after she dies. And so, she moved on to other books and topics. Eventually, we found a lovely stack for Paige to dive into.

As soon as we left I talked to Paige about what had happened: how the bookseller had steered her away from reading about death and pushed her to “lighter fare.” I told her that I disagreed with this tactic, and fundamentally think it reinforces a fear of death and discomfort with talking about the subject.

While I believe that a teenager’s obsession with death can be a signal of some larger emotional problem, I do not think that reading novels where the main character dies is inherently a bad idea for a mature reader. After all, so many of even young children’s favorite characters in television and movies have absent/dead parents; Bambi, Max and Ruby, and countless others have significant adults missing from their lives.

I don’t believe in forcing children to deal with the topic of death in reading until they are ready. I do believe parents are the best arbiters of what information and topics are appropriate for their children. But if a child is comfortable in reading books where a character dies, I believe it’s healthy for the child to do so. As a springboard for an honest conversation about death, it can even be extremely useful in beginning to have conversations at home about it.

Paige’s grandmother was killed instantly in a car crash in the fall of 2009. She learned that the death of a loved one can greet us at any time, whether we are prepared for it or not. By trying to steer my mature child away from the topic, the salesperson contributed to the emotional shielding that makes death a topic that so many individuals (including children) have difficulty thinking and talking about.

June 6th, 2011 §

The rest of my family is coming back today. After a week in Jackson Hole, Clarke and Paige and Colin will return tonight, just in time for Colin’s 7th birthday tomorrow.

The refrigerator has been really empty this week. With just a 2-year old and me, it doesn’t take much to keep us fed. So I took the opportunity this morning to clean out the refrigerator and freezer– really clean them. Take everything out, throw away all the junk, the ice cream that now is just ice crystals. I tossed all of those “placeholders” that you never eat, they just take up room.

As I sprayed a wonderful new lemon verbena spray on the glass shelves, I start contemplating this week. The last seven days were my week to recover from surgery (an oophorectomy), to get stronger, to close out my year. I know I made the right decision not to join my family in Wyoming this year. It’s been a reflective time, a time for my soul to be quiet and heal. I think it’s done that a little. I think another week might help. I’ve loved my one-on-one time with Tristan; we have a nice little routine going, and I feel like he’s grown up this week.

But as the new year starts, of course, we are pushed to reflect on ourselves, to make ourselves better in the next 365 days. We reflexively reflect on whether we’ve kept any of those elusive resolutions from the previous year. December 31st is supposed to bring “closure.” In the arbitrary distinction between one year and the next (after all, why is there really a difference between the last day of 2008 and the first of 2009 any more so than any other passage of midnight on any other day of the year), we are pushed to wipe the slate clean and start anew. As I cleaned the house this week, purging old canned goods, papers, clothing, and sprucing up the house I found I was instinctively doing this: “Out with the old, in with the new.”

This annual rehabilitation, then, is supposed to be psychological and physical.

Most of our resolutions are about ways we want to be better, inside and out: concentrating on the new and gaining closure on the past.

One of my dearest friends wrote to me in an email last week, “And yet, you can no more gain ‘closure’ on life-altering events than you can erase moments from your memory.” I read that sentence many times. It is beautiful, and true.

I remember well when my friend Alex’s father died of cancer almost 10 years ago. She was so busy with all of the things that needed to be done, the arrangements that needed to be made, and taking care of her mother who needed constant attention and support. I remember wondering when she was going to grieve. I worried that his death, and his absence from her life, would fester and haunt her.

As I scrubbed the refrigerator shelves this morning I realized that you never grieve the way you think you should.

No one really just sits alone and thinks about the tragedies that befall them.

It’s too painful, too powerful to take that in as one big gulp.

Instead, what we do is weave it into the tapestry of our consciousness.

We make it part of our daily life, quiet, but present.

Maybe at this time of year we reflect more than usual, and maybe that’s why the holidays are painful as we take stock of what we’ve lost during the year and what we’ve gained.

Where that balance lands says a lot.

A year ago I thought surely 2008 would be better than 2007. It really didn’t turn out that way. But I am doggedly optimistic even when I’ve been been proven wrong so many times. I do not believe that there is a “justice meter” in the universe that is going to now dump things on someone else and leave me alone for a year. But maybe as my own tapestry of consciousness keeps getting woven, it will be stronger and more resilient to keep me going this year.

At least I’m starting with a clean refrigerator.

originally written January 2, 2009. Modified June 6, 2011

June 3rd, 2011 §

More often than not, cancer creeps into conversations with friends. New friends, old friends.

I don’t think I’m obsessed with it. I don’t have to talk about it. Why does it come up?

Is there a cancer radar?

Is it just that when cancer folks are together we let our guard down to share?

Do we want to compare notes and try to get information from each other?

Probably all of the above.

Here’s also where I think it comes from: talking about illness is grounding. It puts the emphasis where it should be. I have many friends who have family members who either have had or currently have cancer. We’re a club. There is a support we can provide for each other, a language we can speak. Stages, grades, blood counts, oncologists, PET scans, MRIs, tumor markers… and on it goes. I really think I should get credit for CSL… cancer as a second language.

I like people who “get it”; I find more and more that I am naturally drawn to them. I’m rarely surprised to find that new friends of mine have had some type of hardship in their lives.

Maybe it’s just that more and more people have “something” in their life story.

Maybe those are the people I gravitate to.

Maybe they are drawn to me (or the “vacuous people need not talk to me” sign I have on my back scares others away).

It’s not that I don’t like talking about shoes or The Bachelorette or movies. I do– a lot. And I actually do think they matter. It’s important to have a break from the heavy, serious stuff. Some people think that the small stuff is all there is– that it matters. Those people are hard for me to take.

One day, shortly after I was diagnosed, I sat watching my son take a tennis lesson. I was still numb and reeling from the news that I had cancer. I hadn’t started chemo, and was still awaiting surgery. I knew what I was facing: double mastectomy and chemo. But to the outside world I looked totally normal; no one would know what news I had received.

There were two moms sitting near me chatting loudly while their kids had their lesson. These were the days before the recession, when women in my town were flush with cash, and living high on the hog. They were talking about vacations. “I just can’t decide where we should go for vacations this year,” one said, “John has so many vacation days it’s going to be hard to use them all. We could go to Switzerland again. But that’s kind of boring. And there’s the Caribbean. But I kind of want to do something different. What do you think?” she said to her friend.

I know what I thought. I thought someone needed to hogtie me to the chair before I punched her out. That was a problem? It was one of the few times I really wanted to say “Lady, let me tell you about a problem.” But I didn’t.

Why?

Because maybe her mammogram was the next day.

Maybe she was a day from being told there was something suspicious on it.

Maybe she was a week away from having a biopsy.

Maybe she was a month from having a double mastectomy.

Maybe she was six weeks from starting chemo.

Maybe she was just about to learn the lessons I was learning.

May 25th, 2011 §

A few months ago I asked my mother to share some thoughts on the difference between guilt and regret (A Psychologist’s Perspective on Guilt vs Regret, February 7, 2011). That post quickly became one of my most-read pieces. When I knew my mom was coming to visit this past weekend I asked, via Twitter, if anyone had any questions they wanted me to ask her.

One reader wrote:

My mom passed away six years ago, when I was 24, after a five-year battle with cancer. I’m getting married in a few months and I’m finding two things difficult: 1) going through a big life change, and the actual planning of the event, is making her loss feel much more at the forefront than I expected; 2) I’m struggling with marrying someone who didn’t know my mother and doesn’t understand (and honestly, not sure how he can, not being there) my grief.

My questions are: how do you help the new people in your life know the person you lost and understand the depth of your grief? And how do you deal with the new kind of grief that comes with entering a new phase of life?

……………………………………..

My mother, Dr. Rita Bonchek, spent her career as a psychologist specializing in grief, loss, death, and dying. She had some thoughts on the subject. I decided to add my own take on it; that perspective appears after hers.

……………………………………….

Dr. Rita Bonchek writes:

In American society, the topic of death causes great discomfort so people do not think about or discuss the subject. When the death of a loved one occurs, the bereaved are often encouraged to put the occurrence in the past. Freud felt that the mourner needed to ” let go” in order to move on. However, when Freud experienced the death of his favorite grand-child, he often expressed with great sadness that he would never get over the loss.

What is not appreciated about the death of a loved one is that “Death ends a life but it doesn’t end a relationship that lives on in the mind of the survivor.” Some studies have shown that mourners hold onto the relationship with the deceased with no notable ill effects.

A childhood death of a parent can be a devastating event. How the child grieves is extremely individual and based on the child’s age when the parent died, the cause of the loss, the quality of the parent-child relationship prior to the death, and the support system available both at the time of the loss and afterwards. If a surviving parent removes all items and pictures of the deceased and does not talk about him or her, the child is denied the grieving process. The secrecy and the inability to have a shared grieving between the child and family that shares the loss is a travesty.

The mourning for a mother never really ends. Even after many years while there may not be active grieving, there are what one child called “mommy-missing feelings.” And what does a mother provide for a daughter: support, advice, a significant person who can help and validate the child during development. No one else is so uniquely important to the child as a mother who helps her to form an image of herself. With this self-image, a daughter is helped to determine how to interact with the world and the people in this world. A daughter’s feelings, thoughts, hopes, desires and attitudes are influenced by a mother. But this mother does not have to be the mother who existed in real life but who is a mother who exists in the daughter’s heart and mind. This is a mother who is carried within a daughter forever.

When a mother-daughter relationship has been strong and positive, a mother loves a child in a very intense and special way. A daughter will miss a mother’s protectiveness, loyalty, encouragement, praise, warmth, and, as the daughter becomes a woman, an adult-to-adult friendship. There are special times in the developing daughter’s life in which the absence of a loving person is painful: graduation, confirmation, Bar/Bas Mitzvah, a wedding celebration, the birth of a child, etc. This is when the wound is re-opened.

Who the daughter was when her mother died is not who she was after the painful event. Every death of a loved one changes us and causes us to re-grieve the loss of other loved ones. Hope Edelman, in her book Motherless Daughters encourages women to acknowledge, understand and learn from the changes that occurred as a result of the early loss of a mother. It can take years. With reflection and understanding of what was lost when her mother died, a daughter can, with greater sensitivity, become her own role model as she creates a strong family and friend network of her own.

…………………………….

I had the following thoughts:

Even though the death was six years ago, it happened to you at a time before marriage and/or motherhood. While not relevant to all women, these are often defining events in their lives. While you had your mother for your childhood, oftentimes daughters do not fully appreciate their mothers until they become wives and mothers themselves. When you no longer have a mother to admit “now I understand what you meant” or “I’m sorry for how I behaved as a child” it can feel that there is unresolved business at hand. Not being able to ask, “Is this how you felt on your wedding day?” or “What was your day like?” is difficult.

Of course, a wedding is one of these events that is tied to family. How can you possibly explain the ways in which these occasions make you miss your mother? As my mom said, it’s not just the relationship you had that you grieve, it’s the relationship you could be having now. There is no way to fill that void, no one can fill that space. I think that incorporating your mother and her memory into your ceremony may provide a way for her to be remembered and present during your wedding. Because your fiance did not know her, he will not miss her in this event. You will, however, as some of the guests at your wedding will too.

It’s a common misconception that talking about your mother or acknowledging her absence will “make people sad.” On the contrary, I believe that talking about her and her absence is appropriate. One way I think this is appropriate is to mention her in the wedding program and/or light a candle during a portion of the ceremony that names those who are “special to us but not here to share this day.” I have seen an acknowledgement of special friends and family who are deceased but remembered on this special day. A paragraph, properly worded, could mention your mother’s role in raising you, making you who you are today, and how you wish she were here to share this occasion. Similarly, wearing a piece of her jewelry or clothing (like a veil) or carrying her favorite flower in your bouquet might help you feel closer to her on the actual day.

Grief sneaks up on you when you least expect it; the reflexive reach for the phone is a hard habit to break. Both happy and sad events can make you miss loved ones. Every little thing reminds you of your loved one, the things you did and the things you had yet to do. You grieve the relationship you lost and the one you had yet to build. The relationship was truncated, and that cannot be fully appreciated by someone who has not experienced it.

I don’t know if you have shared a lot about your mother with your fiance, but I think it’s important to do so before you get married. I think it’s important to write about her and talk about her with him. He’ll never be able to understand fully, and he’ll never miss her since he didn’t know her as you did. But he does need to understand how important she is to you now even though she’s no longer alive. That may not be intuitive– although your mother died six years ago she is still a very important part of your life.

It’s important to say that not all of the memories surrounding your wedding would necessarily be happy; after all, weddings can be prime opportunities for mothers and daughters to clash. However, the pivotal moments of walking down the aisle, first dance, photographs, and so on can be especially difficult.

Sometimes when we grieve we don’t know exactly what we need, and in the end, no one can provide the “fix” for us — that could only happen if our loved one came back. Realizing that you don’t really know what you need all the time as you go through this is important, too. Something your fiance says might be incredibly aggravating one minute (a reminder that “he just doesn’t understand”) but other times the same thing may strike you as supportive. He’s in a tough situation because he’s trying to support the woman he loves on a day that is supposed to be one of the happiest days of your lives together. However, it has a component of pain involved for you. He needs to accept that dialectic and not try to gloss over or erase the pain that will accompany all of the happy days you will have together. He needs to know that grief will be a part of every happy event you will have in the future because your mother is not there to share it. The sooner he can accept that truth, the better it will be for both of you, I think.

I hope that some of these thoughts will help you in the months leading up to your wedding and that you can find a way to incorporate your mother’s memory into your ceremony. I know she will be in your heart and on your mind.

May 18th, 2011 §

A few weeks ago I was talking with a friend about our blogs. She said that she never writes about her husband; some readers didn’t even know she was married. I don’t directly write about my husband Clarke often. I’ve written endlessly about his mother Barbara’s sudden death in a car crash in 2009 (if you want to read more about her, please click on the tag “Barbara” on the lower right of the page) but not about Clarke. Clarke is private, and I respect the fact that he doesn’t want to write or discuss topics that I do.

Clarke wrote a piece that I treasure. In 2009 he nominated me as a “Brave Chick” for a website that celebrated women who had tackled adversity (www.onebravechick.com). The interesting thing to me as I re-read the essay now is how much more has happened since then. We’ve had many medical and emotional challenges since this letter was written. I like to think that the seeds of strength were sown during some of these experiences.

I am re-posting this today not to celebrate myself, but rather to celebrate my husband. We are a team in this thing called life and I couldn’t do it without him. I hope I will get him back here on the blog sometime to write about some more of the issues we have dealt with; I think hearing it from his point of view might be helpful for some readers. But for now I will let his words sing, and hopefully honor him by doing so.

…………………………………..

“The bravest sight in the world is to see a great man (or woman) struggling against adversity.”

-Seneca

“Let us do our duty, in our shop in our kitchen, in the market, the street, the office, the school, the home, just as faithfully as if we stood in the front rank of some great battle, and knew that victory for mankind depends on our bravery, strength, and skill. When we do that, the humblest of us will be serving in that great army which achieves the welfare of the world”

-William Makepeace Thackeray

My wife Lisa and I met for the very first time at the George Foreman / Evander Holyfield fight in the spring of 1991 when, in a scene straight out of Rocky, a forty-two year old Foreman went the distance with the undefeated Holyfield. We met again at a Halloween party later that year and began dating. We got engaged in 1995 and married in the summer of the 1997. Over the course of our 18 years together and in particular the last three, it has become clear to me that my wife possesses more than her share of courage.

As with any 18 year period we have had our ups and downs together but mostly it has been up. We have three beautiful and intelligent children, loving and supportive families and great friends.

In the grand scheme of things, our life together was pretty smooth which is why I think we were completely unprepared for what the last three years have brought us. In August of 2006 we learned that our five month old baby boy was born with a condition that required immediate open heart surgery. He also had complex problems with his cervical vertebrae and the muscles of his hands that would require a significant ongoing investment of time and energy in medical care and therapy.

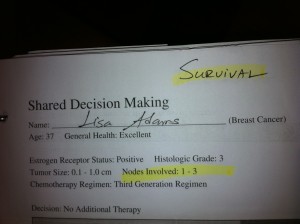

Since Lisa is at home with the kids when I’m at work, the day-to-day heavy lifting of running the house and managing the often crazy logistics of our lives naturally fall to her. In addition, because she is the medically savvy one in our family (her father is a surgeon and her mother is a psychologist), Lisa ended up quarterbacking and supervising Tristan’s care which included (and still does include to some extent) coordinating treatment with four or five different specialists (neurologists, pulmonary specialists, pediatric cardiothoracic and orthopedic surgeons, etc.) in three different cities. Juggling all of those competing priorities was extremely challenging and time-consuming. It seemed like fate was piling on hardship in January of 2007 when Lisa was diagnosed with Stage II breast cancer.

Lisa spent much of 2007 aggressively treating her cancer with a double mastectomy and chemotherapy. I’m sure many women who read your website are acquainted with the harsh reality of how tough a cancer treatment regimen can be on one’s body and, just as importantly, one’s psyche. I must confess that I wasn’t really prepared for what was to follow. Like many things, cancer treatment seems much simpler in the abstract or on television than in the messy reality of real life. It is a process where you are forced to make life-changing and often heartbreaking decisions while in possession of only limited information all the while dealing with the physical, mental, and emotional side effects of disease itself and the treatment. If adversity is the test by which character is revealed then I’m proud to say that my bride has passed her personal test with flying colors.

At least by the romanticized ideals of literature or history you don’t get to see real bravery very often when you live in Darien, Connecticut (braving the long lines at the local Starbucks doesn’t really count). However, there was something quietly heroic in how Lisa handled the myriad of issues she was dealing with in a thoughtful and calm (with some exceptions) manner all the while taking care of the thousand little details that go along with being a mom to a young family. No matter how much personal pain she was in, the kids’ lunches got made, their homework got done, their boo-boos got kissed, and their very real fears addressed and soothed even on the very worst days. Tending to young kids isn’t easy on your best day but being able to do so and face the world in the midst of cancer and chemo and all that implies is something else altogether.

Looking back, the amazing thing to me is how little impact the whole period had on our children; that speaks to how much of her energy and force of will Lisa put into ensuring that that was the case. We had lots of help from our families and our amazing group of friends, but at the center was Lisa getting up each day and doing her best to move forward with grace and determination (kind of like a 42 year-old George Foreman coming out of his corner, taking his licks and getting in some good shots of his own). In my book, that is all any of us can really expect of ourselves and defines what bravery is all about. When my test comes, I hope I do as well and face up to it with as much strength as Lisa did.

A friend whose wife had just gone through the breast cancer experience told me when I learned about Lisa’s diagnosis “the thing about breast cancer (pardon another tortured sports metaphor) is that you never get to spike the ball in the end zone and say you are done. There is always something else.” I thought I understood what he was saying at the time, but I appreciate it much more now. Although chemo ended in the summer of 2007 and her breast reconstruction finished shortly thereafter, Lisa has been dealing with the often frustrating regimen of drugs and side effects that come along with being a cancer survivor. While things are certainly better than they were, it has been a constant challenge and adjustment for both of us.

As I said earlier, one of the most difficult things about having cancer, even a cancer that is as common and well known as breast cancer, is that you really don’t have any idea what is ahead of you as either a patient or a spouse when you begin the process. There are reams of data and academic studies available but despite that fact, it is difficult to distill and digest all of that into a coherent picture as to what you as an individual (or the spouse of one) will experience.

As part of her life as a cancer survivor, Lisa has taken it upon herself to make understanding the long road of treatment, recovery, and being your own best advocate a little easier for women who will face the same challenges she did. She spends hours and hours speaking to women in our community who are just beginning the process about what she has been through in the hopes it will help them be prepared. As an extension of those conversations she began writing (and later blogging) about her experiences and feelings about cancer and posting them on the web. She sometimes writes clinically about the nitty-gritty medical realities of treatment and recovery which are based on her personal experiences, extensive research of the available medical literature, and her own conversations with her doctors.

Other times she examines the darker, emotional, frustrating, and deeply personal places that being a cancer survivor can sometimes bring you as young woman and a young mom. Her writing is often beautiful and poetic and is always thoughtful and enlightening. She puts it all “out there” for public scrutiny. She posts regularly under her own name to help her fellow women (our moms and sisters and daughters) understand and deal with a path that all too many of them will walk down at some point in their lives. I believe this is noble and selfless and courageous.

So as a very small and modest way of acknowledging her daily efforts and recognizing her achievements, I would like to nominate Lisa Adams (age 39), loving wife, wonderful mother, caring friend, talented writer, and strong cancer survivor to be a featured brave chick. I would invite those members of your community who are interested to check out her writing at lisabadams.com.

Thanks for your time and dedication to Brave Chicks everywhere.

Clarke Adams

July 7, 2009

May 13th, 2011 §

One of the defining features of childhood is innocence.

As children we don’t realize that things change. We think the way that things are when we go to bed at night is the way they will be in the morning. We put the bookmark in our lives and expect everything to be the same when we return to it.

Of course, as we grow we realize that’s not true.

That it can’t be true.

That’s not how things happen.

That’s not the way the world works.

And what do we say when someone still believes it? We say he is being childish.

Oftentimes I wish I could retreat to childhood. Not because of how my childhood was, but because I want to recapture that mindset, the one that says that everything is going to be alright. When people tell me “everything is going to be fine” I snort. I recoil. I don’t believe them.

It’s not always going to be alright.

Sometimes it is. Sometimes it isn’t.

But the road you must take to figure it out might break you before you ever find out for sure.

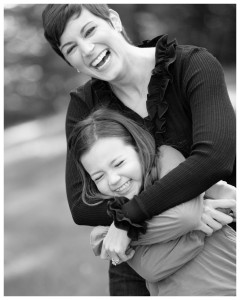

May 8th, 2011 §

I can do better, but I have done my best so far.

I’m not the fun mom, but I’ve taught my children big lessons in their young lives.

I try to be a good wife, mother, daughter, friend.

I try to inhabit the womanly roles even when I don’t always feel feminine.

I spend a lot of time inside my head,

twisting, pulling, ruminating.

It doesn’t mean I’m sad. It means I’m thinking.

I’ve made mistakes,

I regret some of them.

But my children are not those mistakes: they are my legacies.

I look at them and wonder how it can be that Clarke and I have created three people. Literally given them life.

It is a joy for a mother to see her children grow,

learn to inhabit the space they take in the world,

learn to own that property.

It’s as if children need to learn the size of their bodies– the breadth of their being– in order to go out into the world and participate in it.

I love watching this process unfold.

I can do better in the future, but I have done my best so far to mother them.

And really, that’s all anyone can ask.

May 4th, 2011 §

I decided to repost this old piece after reading Katie Rosman’s Wall Street Journal piece “Read It and Weep, Crybaby”

September 3, 2009

It’s 11:30 in the morning and I’ve already done it once today. Cried. Not sobs. But a quiet, empathetic cry. Large tears welling.

It happens less than it used to. I have gotten better at managing it. I can now get to the point where I well up, but the tears don’t actually spill out and run down my cheeks.

It’s progress.

That difference seems to make people less uncomfortable. My doctors are used to it; they know I well up. I figure if you’re dealing with cancer patients you are used to seeing lots of crying– you must have a coping mechanism. Maybe it doesn’t even register anymore. Maybe they are immune to it. I see tissue boxes in all of their offices so it’s likely a common occurrence.

There are certain subjects guaranteed to make me cry.

Tops on the list?

My parents; my mother in particular. Raise the subject of anything happening to my mother— any illness, any harm, most especially her death– these words if spoken aloud instantly make me cry.

My mother is, to me, a prized possession, a beloved security blanket that must remain complete and undamaged.

Other topics do it too.

Today the trigger was talking about a specific day I was bald in front of my plastic surgeon. I remember the way I felt stripped of every ounce of dignity in a way that being naked, topless, breastless countless times in his presence had never made me feel. Obviously I can still connect to that emotion.

I still remember that feeling of being naked. Not clothes-less, but dignity-less, bare of everything that held me together as me. Sitting in a coffeeshop with music playing and the sun shining and my friend sitting with me, I could still feel that feeling two years later.

I could still feel it. And I cried.

I cried for the friend I was with, herself recently diagnosed with breast cancer.

I cried because I didn’t want her to have to feel it too.

I cry for her sometimes. I cry because I want to protect her. I want to be the pit bull. I want to stand guard at her driveway, at her mailbox.

“NO!” I want to yell.

“You cannot have her,” I want to say to the intruder.

To cancer.

To all of the things she might have ahead of her that will cause her pain.

Silly, perhaps.

Childish, perhaps.

But that’s how I feel.

I bet that’s how she feels.

I know that’s how I felt.

As a person with cancer you wake up and think,

You know what?

I don’t want to have cancer today.

I want to take a day off.

I don’t want to go to any doctors.

I don’t want to make appointments.

I don’t want to talk about cancer.

And even though I can’t seem to talk about anything else,

I don’t want to talk about it.

I just want to stay in my pajamas all day

and eat peanut butter from the jar with a spoon

and have the world go on without me

because I don’t want to participate today.

I just want a “sit it out today” note from my mom

so I can just take a break today…

and maybe tomorrow too…

I want to protect my friend.

We moms are good at that.

My daughter started middle school. On the second day she came home and started in on her math homework. Within minutes she was in tears. She got frustrated and started crying. The teacher had given them a very hard sheet of problems and told them to see what they could do. Some of them were complex probability and statistics questions. She brought them to me and was frustrated. I didn’t laugh at her. Or even criticize her for over-reacting. I knew what she was feeling. I knew it was the “everyone else knows what they are doing and I’m the only one who doesn’t” syndrome. I knew that, like me, when frustration takes hold, our kind doesn’t get angry, we get emotional.

It’s not a great trait; it is especially hard for men to deal with. For husbands. For fathers.

My father used to go crazy when I started crying. It was just an irrational, irrelevant act he had to deal with. A distraction.

I know if my husband had been there he would have told our daughter to stop crying. I know the tendency won’t serve her well.

I always think of Tom Hanks’s character Jimmy Dugan in A League of Their Own when he yells “There’s no crying in baseball!”

It’s a good thing there wasn’t a sign on my oncologist’s door that said “There’s no crying in cancer.” Some days I think it’s a necessary part. I think it’s healthy. For me anyway.

I’ve cried on Saturdays.

On my birthday.

I’ve had breakdowns stringing Christmas lights on the trees in my yard when I just couldn’t get it right.

I’ve kicked the tires of my car.

I’ve slammed doors.

I’ve screamed to the sky.

I’ve sworn a blue streak.

I’ve cried so hard my stomach turned inside out and I’ve retched and collapsed because I just couldn’t hold myself up anymore.

I’ve dreaded the night-time because I knew I would be scared and my dreams would frighten me.

I’ve taken medications to muffle the anxiety of the chemo treatments I knew were about to come.

I’ve been terrified and wondered how I was going to get through it.

I’ve faked it and smiled and been the portrait of strength and composure while ready to crap in my pants because I was so scared inside.

I’ve felt the chemo needle go in my arm bringing the drugs in, felt the cold liquid hit my blood and wanted to scream “Wait! I’ve changed my mind! I think it was a mistake! I think it wasn’t me! I think you got it wrong!”

I felt the pre-medication go through me, hit my brain, cross the blood-brain barrier and fog me up.

Pausing, knowing it’s in me.

Thinking

Please.

Please.

Do your work.

Save me.

Drugs, do your work and save me.

How will I know if they did? I won’t.

I don’t say I’m cancer-free. I have no idea if I am.

I will hopefully die of something else and I will have my come-uppance. I will give cancer The Finger.

I will have it say on my tombstone:

Hey, Cancer: I laughed last. I died of something else.

So, call me a crybaby.

I prefer to say I experience the world richly.

Either way, I make no apologies for my tears.

That’s the kind of girl I am.

May 3rd, 2011 §

There isn’t one right way to react to loss. And the thing about grief? It’ll sneak up on you precisely when you’re not looking.

This morning I attended a memorial service for a 38 year-old mother of two. She died of complications from leukemia, leaving a loving husband and two children behind. We were connected by a shared friend and a diagnosis of cancer.

When Kellie was diagnosed fifteen months ago and learned she needed to have chemotherapy I offered her my scarves. I had an extensive collection from my months spent without hair and had been serially loaning them out to friends after my hair grew back. After they’d covered my head, they’d gone to a friend’s sister in Colorado who had breast cancer. Then they went to a friend down the street who also had breast cancer. The fourth head they touched was Kellie’s.

During that time I had to deny others the use of the collection. I know too many women who’ve had cancer, I thought. There isn’t a break in between their tours of duty. The scarves don’t rest, they just keep traveling.

Perhaps some might find it icky to wear a scarf of someone else’s. That never seemed an issue for my friends. In fact, their softness from being washed so often was a bonus; heads are sensitive when hair comes out and the softer the cotton is, the better.

Kellie had those scarves for a long time. Her own fiery red hair was long gone; my scarves were a poor substitute for that ginger hair of hers. I like the thought of her having something comforting and cheery to cover her head during some of those difficult days though.

After the service today the guests stood talking over coffee and tea and far too many sandwiches and baked goods. Unprompted, our mutual friend assured me the scarves were safe and would be returned soon. I know when the stack comes back I’ll touch the scarves longingly, wishing Kellie were delivering them herself.

I’m overwhelmed today with emotions… sadness at the second Mother’s Day without my beloved mother-in-law, anger at cancer for claiming another young mother, frustration that oncology is often an art more than a science, worry that it will happen to me.

I just need to think. I just need to cry. I just need to remember. I just need to live.

April 11th, 2011 §

The months and years go by. Like all of you I mourn the quick passage of time. “Where did the fall/winter/year go?” I hear my friends asking.

The months and years go by. Like all of you I mourn the quick passage of time. “Where did the fall/winter/year go?” I hear my friends asking.

Projects we hoped would be accomplished — tasks we hoped would be done — sit unfinished. Organizing photos, cleaning out a closet or a room, reading that book a friend recommended; many things went undone in the dark and cold months of winter.

Maybe there were emergencies, maybe there were health issues, maybe you just couldn’t get the energy together to accomplish everything you wanted.

Regardless the reason, there can be a bit of disappointment when a season ends.

Growth happens in fits and spurts, not with smooth, sliding grace.

With each phase comes

pain,

discomfort,

unease,

restlessness,

sleeplessness,

yearning.

At the time of my mastectomies the reconstructive surgeon placed tissue expanders in my chest. These were temporary bags of saline that would be slowly filled to stretch out my skin to make room for the silicone implants that would eventually take their place. Each week, like clockwork, I returned to my surgeon’s office. He accessed a port in each expander with a needle and added saline to each side. Each time after a “fill” my chest would feel tight. The skin wasn’t big enough for the volume inside, and it would react to the increased pressure by stretching. Until the skin could replicate there was achiness, tightness, a slight ripping or tearing feeling.

A similar sensation happened to me during my pregnancies. The growth happened fast; I got stretch marks. I had visible proof my skin just couldn’t keep up; the growth was too rapid, too harsh, too vigorous.

I often wonder if mothers and fathers get psychological stretch marks when we are asked to accommodate changes we’re not quite ready for.

What can we do? What options do we have? None. We must “go with the flow” and do the best we can. Our children grow and change whether we like it or not. We do them no favors by trying to protect them, coddle them, and keep them young.

We give them wings to fly when we give them tools to be

confident

and caring

and inquisitive

and trusting

individuals.

I am often moved to tears as I watch my children grow.

I sit in wonder at the succession of infancy, childhood, and adolescence.

I know that as a mother I lack many skills, but I also know that the words I have written in my blogs and essays will one day be a gift to them too.

Not a gift to the children that they are, but instead a gift to the adults that I am raising them to be.

Each August as they go back to school I marvel that another school year has passed and yet another is here.

No matter how you measure time it always goes too fast.

The growth happens too fast.

The growing pains hurt.

The stretch marks might be invisible, but they are surely there.

April 7th, 2011 §

I’m cranky, I’m sad, I’m frustrated.

I don’t want to explain how I feel to family members. I don’t want to have to.

I want to yell, “If you’d had cancer you would understand!” But I know their ignorance is my prize… the prize I get for the fact that some of the people I treasure most haven’t had cancer.

I’ve seen a comaraderie that comes with this disease.

We may have had different types of cancer, different treatments, different prognoses… but… we are tied together.

When I was diagnosed one of the first things I was struck by was how vulnerable I felt. I worried about my family, especially my (then) seven-month old son Tristan who had his own medical problems. “Who will fight for him?” I thought. “No one will love him the way I do. No one will be his advocate the way that I will. I have to do it. I have to be here for him. I have to do what it takes to stay alive.” That became my mantra.

But once introduced, the worry could not be abolished. It could be dampened, minimized, controlled. But it could not be removed.

Two days ago a high school classmate died of brain cancer. Today I got word that a woman I know is in intensive care after complications from leukemia.

I ache for their families, for their children. I can’t explain the nuances of these feelings well. I have been here at the keyboard trying to find the words and repeatedly come up short.

And so, perhaps it is enough to say that I don’t always have the right words to convey what it is I am feeling.

But that doesn’t mean I feel it any less.

March 14th, 2011 §

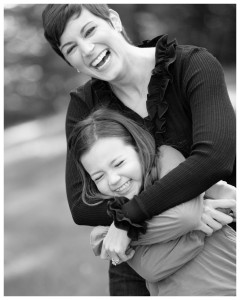

My parents came to visit on Saturday. They stayed for 24 hours, took the kids out for dinner that night and played lots of games of hide-and-go-seek. Nothing extraordinary, nothing particularly notable. It is in these ordinary moments that I find the most pleasure… seeing my parents and my children enjoying each other’s company.

My mother arrives like an environmentally conscious Santa Claus, toting a reusable grocery bag full of mysterious treasures for the kids. Many are newspaper clippings: suggestions for books or reviews of movies they might have seen. Often they are word or logic puzzles from their local paper; for me there are usually cartoons. There’s usually something from the dollar store. Tristan is usually obsessed with whatever she brings while she is here; as soon as she leaves, so too does his interest in the item (hence the inherent beauty of the low price).

Another bag of my mother’s always contains her current knitting project. She knits in the car while my father drives. Tristan loves to wrap the house in the balls of yarn; he criss-crosses the furniture legs, counters, and walls until they are spiderwebbed. Paige has learned to knit and whenever Nana comes she enthusiastically picks up her project to join in while my mom knits. Mom knits wherever she goes. Watching Colin’s tennis lesson, sitting and listening to Paige play piano, watching Tristan ride his tricycle. She almost never looks down at her hands, something I was never able to master.

It was warm and sunny this weekend… a welcome break from the endless weeks of snow, ice, and cold we’ve had here in Connecticut. My mother sat out on the front step with Paige and they knit together while Colin shot baskets and Tristan rode his bike. I peered out the window from the kitchen at them sitting there. It made me sad and happy at the same time. I tweeted: “My mom is outside on front step teaching Paige advanced knitting techniques. I smile, I miss my MIL (mother-in-law), I feel lucky to see this moment.”

I can’t separate out the happiness of seeing my children with my mom with the sadness of wishing Barbara were here, too. Maybe that’s selfish. I know there are so many children who don’t have any grandparents that are alive, and mine still have three. But that is part of grief, I think… the effect it can have on happiness. It takes the purity away. I couldn’t just be happy to see the scene; I necessarily wished their other grandmother could have those moments.

I grabbed my phone and went outside. I wanted to capture the picture so mind won’t forget. Children often remember the quiet moments more than the big, fancy events. Paige will always associate knitting with my mom… she’s treasure the talks they had, side by side, as she knit and my mom helped her when she made a mistake. For Colin, having my dad watch him play tennis is one of the ways he likes to share with my parents. He’s proud, and knows my father is proud of him. He always gives a resounding “YES!” when I say Grandpa will be there to watch him play.

After my mom left Paige continued to knit. Shortly thereafter I knocked on her bedroom door. She answered, tears welling up in her eyes. She told me she had made a mistake. She had tried to correct it, but further wrecked the piece she was working on. She had ripped all of her work out. She would start over.

And so she did. And now, as I type, she’s sitting in a chair working diligently to recreate the work she destroyed. I know she’ll work until she goes to bed.

I know how quickly life can change.

For now, I revel in the glory of the ordinary, the everyday, the mundane.

March 6th, 2011 §

Written September 19, 2009

I put makeup on for the first time in days.

I don’t know why.

I know the tears will wash it away.

But it’s a step.

Today, with complex fractures still unset in his right leg,

My father-in-law got out of bed and hopped with a walker.

I don’t quite know how.

But that’s the kind of guy he is.

He will have more surgeries on Monday.

He’s going to have at least twelve weeks without weight-bearing.

His wrist is set, with a plate.

His knee fracture will get repaired on Monday, too.

He’ll need months of physical therapy.

But it’s a step.

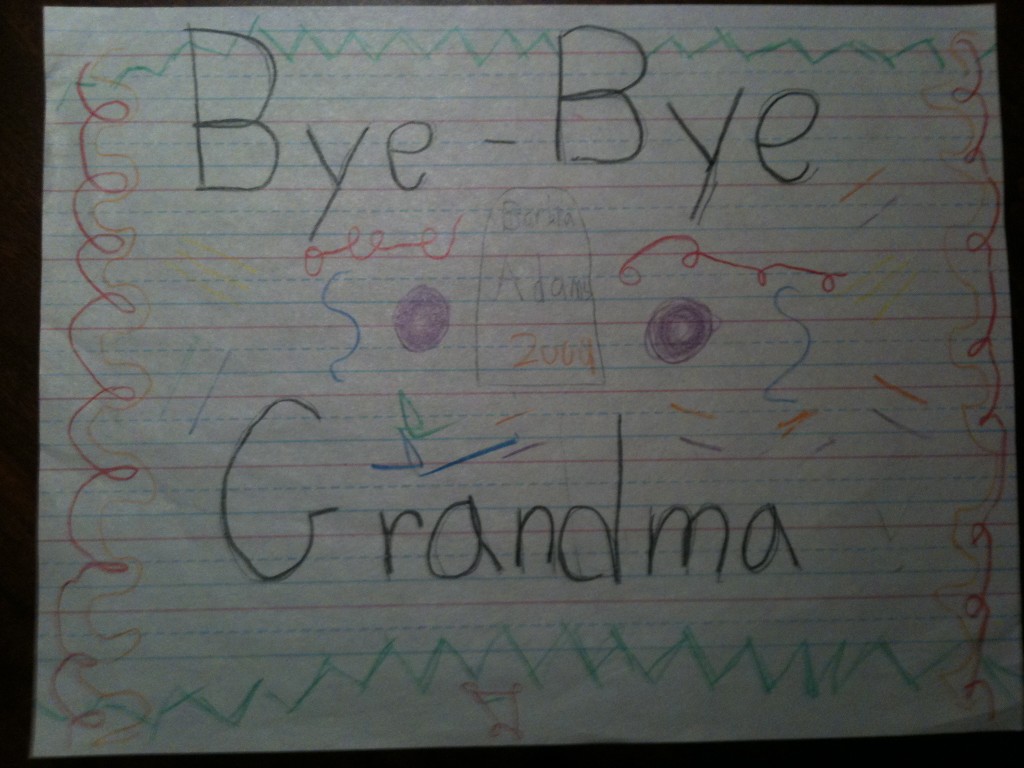

Colin, age 7, was just sitting at the kitchen table.

He had a plastic bone-shaped toy and

Had placed a piece of paper inside.

I asked what it said.

“Grandma 2009” he said.

And he wrapped Scotch tape around and around the bone to make

Sure the sides didn’t come apart.

“It’s like a memory box.”

“Oh,” I said, trying to hold back the tears.

“I think that’s nice.”

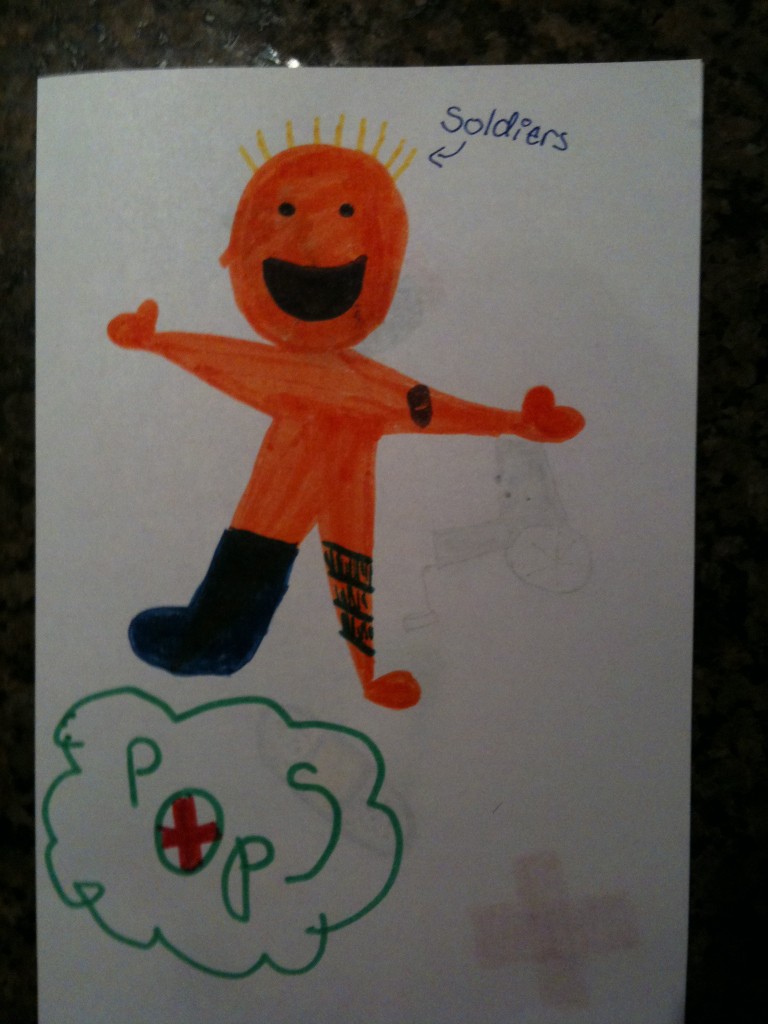

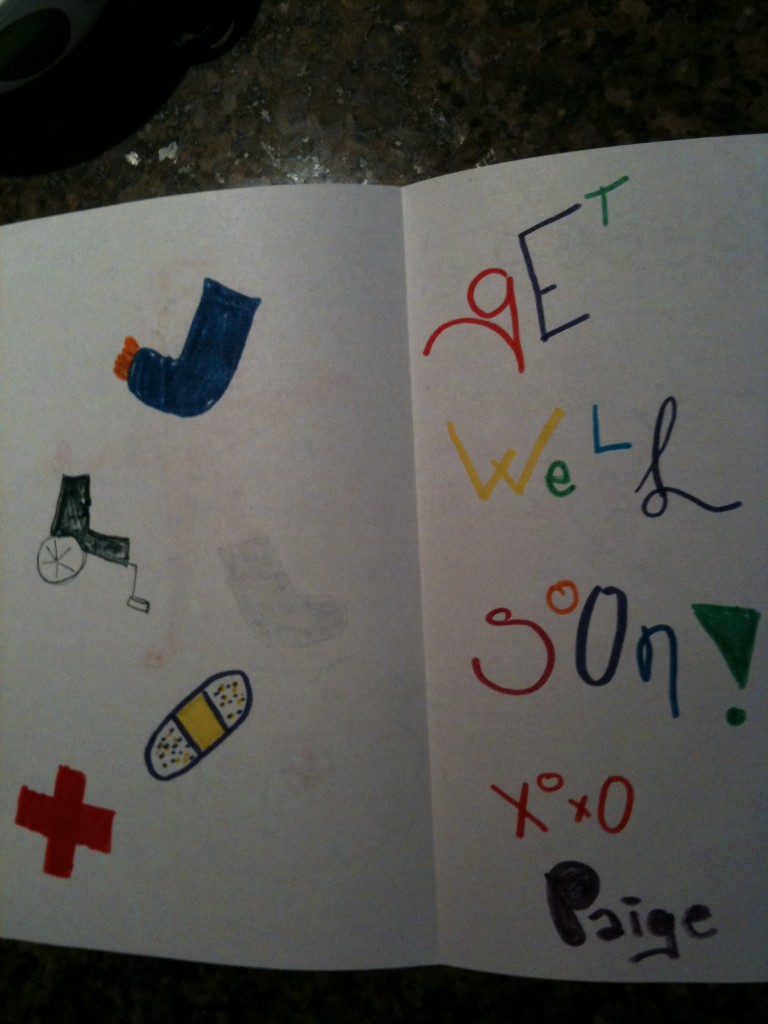

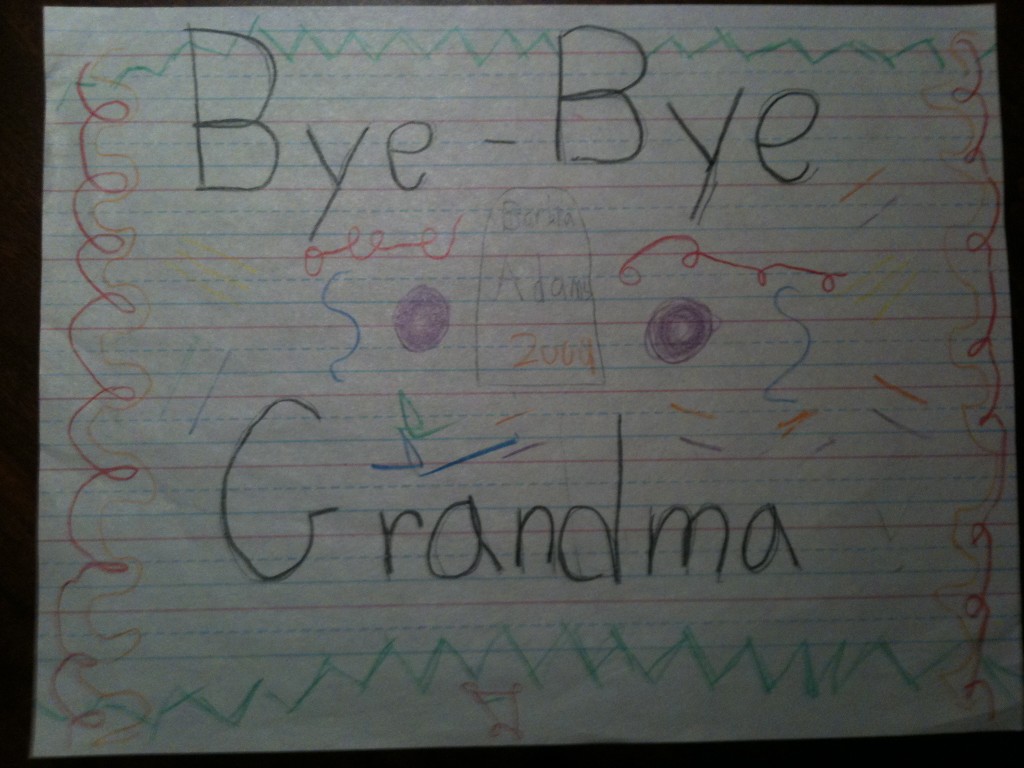

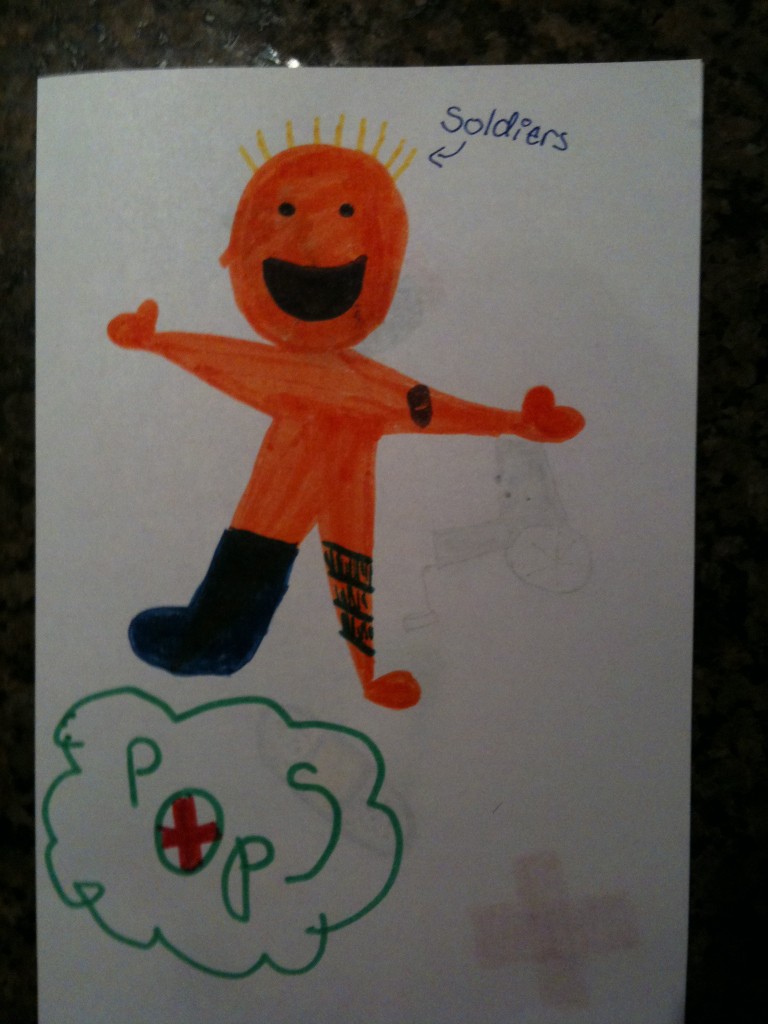

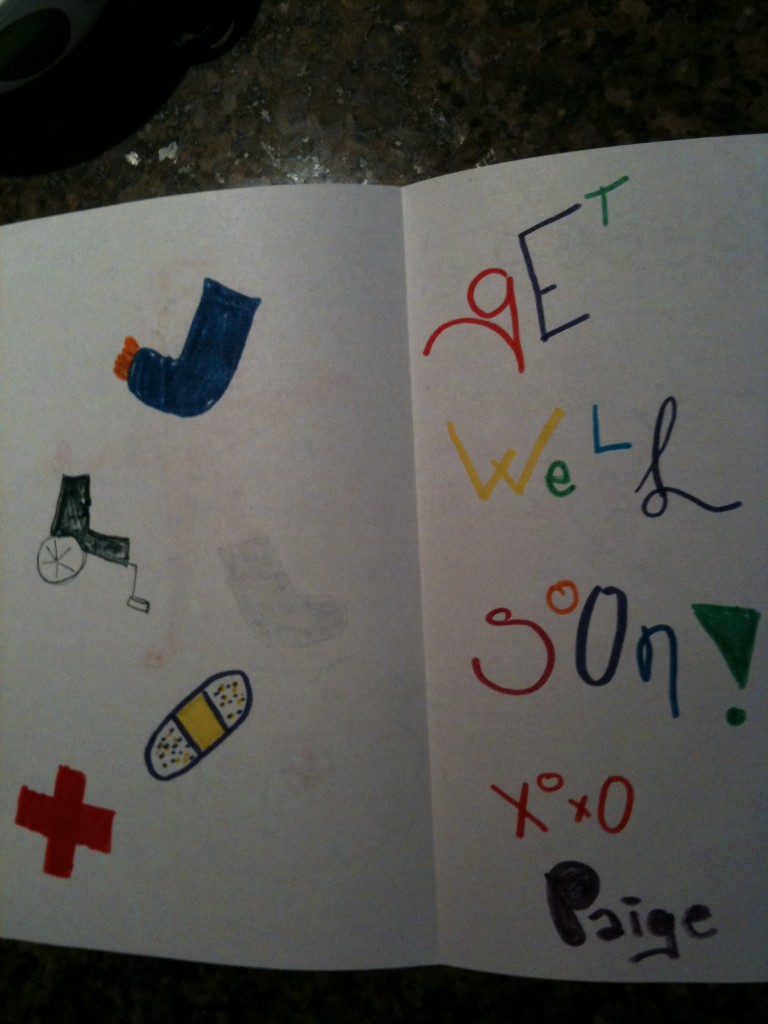

Paige is making a “Get Well Soon” card for Clarke to take to his

Father tomorrow when he goes to see him.

I am sitting in the other room and the thought of it

Brings me to tears.

I’m almost scared to go and look at it.

I just know it’s going to be so special.

So wonderful.

So filled with love

and innocence

and childish adoration

that it will be happy and sad

all wrapped up in one.

It will be painful for him to read I bet.

Being half of “Grandma and Pops”

is going to be like limping along…

But

I keep

reminding myself:

even

a limp

is a step.

March 6th, 2011 §

Written September 18, 2009

I had a lot of breakdowns today.

At Starbucks talking to my friend Brenda.

In my car.

Talking to the director at nursery school.

The most embarrassing?

At the deli counter.

Looking at tuna salad.

The sight of tuna salad made me cry.

Two weeks ago I asked for a small container of tuna salad.

The way I always did when my in-laws came to visit.

Tuna salad from Palmer’s Market.

It was my mother-in-law’s favorite.

Nineteen days ago she sat at my kitchen table.

Twenty days ago I asked for tuna salad.

I just want to ask for tuna salad again.

I just want to say to my favorite deli counter man,

“My mother-in-law is coming to visit,

So I need to get more tuna salad…

You know how much she loves it!”

I just want to say those words.

I just want to make her a tuna sandwich.

That’s all.

Just a little thing really.

Just a sandwich.

Is that too much to ask?

Does that truck driver know that?

That I just want to share a sandwich with my mother-in-law?

I just want to hug her,

Hear her voice,

The way she liltingly said my name when I answered the phone.

The way she said “hello” in a special

Sing-songy way when I called her.

I think of the cotton nightgowns she loved so much.

The way she hated the last haircut she got in Jackson Hole.

How she wondered if they were still wearing linen in

Connecticut in August and if she could wear a linen blazer for

David and Bronwen’s wedding.

How she loved the note paper I got her for her birthday last year.

How she played Webkinz games on the computer

Just to be able to have something to talk to the grandkids about.

How she was jealous I got to hold Baby Owen the day after

He was born this week.

How she was making plans to come and see him.

Does that truck driver know that?

Does he know she had a brand new grandson two days old that

She didn’t get to hold?

Does he know he killed her on her son David’s birthday?

Does he know he killed the mother of six children?

Nine grandchildren?

Many more to come?

Does he?

I bet not.

I haven’t been able to eat more than a few bites since Barbara was killed.

I wonder if the truck driver has.

I wonder what he’s having for dinner in jail.

I wonder if he’s going to have tuna salad.

Because right now,

When I think of it,

All I can do is cry.

March 6th, 2011 §

Written September 18, 2009

Children are different.

From adults.

From each other.

I had to give two of my children different directives this morning:

One I told, “It’s okay to be sad.”

One I told, “It’s okay to be happy.”

I needed to tell my 7 year-old son that it was okay to cry, to be sad, to miss his grandmother.

I miss her too.

And it’s okay to let your emotions show.

It doesn’t make you a sissy or a wimp.

What it does make you is a loving grandson.

A grieving boy.

A bereaved family member.

But my ten year-old daughter needed a different kind of permission slip today.

I sensed she needed permission to smile.

To laugh.

To be happy.

I needed to tell her that it was okay to forget for a moment.

Or two.

To forget for a few moments that Grandma died.

It’s okay to still enjoy life.

The life we have.

Grandma would want that.

I told her that Grandma loved her so much.

And was so proud of the person that she is.

I reminded her how Grandma’s last phone call here last Sunday was specifically to tell Paige how proud she was of her for walking in the Komen Race for the Cure with me.

It’s okay to still feel happiness.

And joy.

It’s okay to let that break through the sadness.

Children are different.

But they take their cues from us.

I know my children.

I know that this morning what they needed from me was a sign that it was okay for them to feel a range of emotions.

It’s healthy.

Because what we are living right now is tragic.

And confusing.

And sad.

And infuriating.

If it is all of those things for me,

It can only be all of those things and more

To my children.

March 6th, 2011 §

Written September 17, 2009

She went up to bed tonight,

Still pink-eyed and shaky.

Finally calmed enough to hopefully get some rest.

And as she walked into her room,

Somehow,

From beneath her bed,

The bright kaleidoscope patterned paper

Caught her eye.

I heard the sobs,

The wails,

The primal,

yearning,

cry.

“My birthday present.

From Grandma.

The one she gave me early.”

She stood pointing at it,

Gaze averted,

Like a child pointing at a dead

Animal in the middle of the road.

Together we looked.

And then all at once it hit me.

I knew what she was talking about.

Two weeks ago,

When my in-laws were visiting,

Paige’s grandmother had given her a wrapped box

And said,

“This is for your birthday.

Put it somewhere safe.

Don’t open it until October 28th.

I know it’s something you’ll like,

But you have to wait until then,

Okay?”

And so,

Because that’s the kind of 10-year old she is,

Paige didn’t peek,

Or lift the corner of the paper,

Or ask her brother what was in it.

Instead,

She carefully put it under her bed

To wait until October.

We had no way of knowing we’d never see Grandma

Again.

No way of knowing that was the last present that would be

Bought.

No way of knowing that a truck which had no business

Trying to pass anyone,

Much less several vehicles at once,

Would slam head-on into my in-laws’ car and kill our

Loved one.

Tonight,

The very sight of the box,

And the thought of its giver,

Brought her to tears,

Racked her with sobs,

Riddled her with grief,

Filled her with anger,

And sadness,

And loss,

And pain,

And confusion,

And did the very same

To me.

March 6th, 2011 §

written September 17, 2009

I didn’t even recognize his voice when

I answered the phone last night.

It was my husband.

And through the sobs

He told me there had been an accident.

A car crash.

His parents.

Driving from their home in Jackson Hole

To their home in Scottsdale.

A truck had tried to pass some other vehicles

Around a slight bend.

The truck only got alongside an oversized load

when they collided,

at highway speed,

Head on.

In their lane.

The passenger side took the impact.

My beloved mother-in-law,

Barbara,

Killed instantly.

Mother to six,

Grandmother to nine,

Including newest grandson Owen born only two days ago.

Truly beloved woman.

We all grieve her loss.

We ache.

We are stunned.

Clarke’s father, airlifted to Salt Lake City.

Awaits surgeries for his injuries.

Already surrounded by relatives.

More scramble and scurry to be at his side.

We cry and mourn and try to make sense.

There is none to be made.

No reason,

No explanation.

Or maybe there is:

A stupid decision

By a stupid driver.

A moment’s impatience

Let to a

A split second acceleration

But a miscalculation

Let to a

Fatality.

Problem?

Wrong person died.

Wrong person paid the price.

Don’t tell me any logic.

Don’t tell me any cause.

Don’t tell me any plan.

Don’t tell me she’s in a better place.

Don’t tell me she’s looking down on me.

Don’t tell me anything good.

Don’t tell me anything about anything.

Right now

All I feel is pain.

All I know is hurt.

And now?

Now we have to tell our children.

Grandma’s dead.

March 6th, 2011 §

I’m going to be bringing over many of the posts I made when Barbara Smith Adams died on September 16, 2009. I find myself crying reading my words again… reliving those confusing, tragic, raw feelings that I had when I first got the news. I want to have those posts here on the new site; eventually the old website will be taken down. These pieces are some of the ones I am most proud of. Perhaps that sounds odd to say about writing that came from grief. However, to me they are a documentation of my love for a woman I was privileged to call my mother-in-law. I had nineteen years of knowing her, and they weren’t enough.

Every day something makes me think of her.

It might be the necklace I wear that was hers.

It might be my daughter’s round face which looks so much like Barbara’s.

A milestone for Tristan,

a family gathering,

any holiday,

my spring garden,

a pretty set of linens,

a family vacation,

Colin’s essay about making snow ice cream with her…

it’s anything.

I think of her all the time,

and I cry.

February 7th, 2011 §

I’ve written previously about my decision to have my ovaries removed two years ago in order to (hopefully) decrease the likelihood that my breast cancer will recur (“The Impetus of Fear”). Though I tested negative for the BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 genes, my hormone receptor positive cancer feeds off of the hormones that my ovaries produced. To significantly reduce the amount of those hormones circulating in my body (as a pre-menopausal woman of 38) I decided to have a salpingo-oophorectomy (surgical removal of my Fallopian tubes and ovaries). I recovered from the surgery itself within two weeks; the effects of plummeting into menopause overnight have been longer-lasting and in some cases, quite devastating.

As I do with almost any issue in my life, I have repeatedly talked to my mother, Dr. Rita Bonchek, about the ramifications of my decision. This angst has led to many talks about the difference between regret and guilt. As a psychologist specializing in issues of grief, loss, death, and dying for twenty years, she always has a keen ability to separate out what appear to be muddled feelings. She often has ways of explaining complicated topics in easy-to-understand terms and using real-life examples to illustrate her points. She and I have collaborated here to present some thoughts on these two emotions. The ideas on the differences between guilt and regret are hers; I have pushed her to explain things as fully as possible and helped with some of the re-writing.

We hope that they will help you to think more clearly about actions in your life and the emotions you have about them. We look forward to hearing your comments and any follow-up questions you have. Because my mom is not on Twitter, if you have any questions for her, it’s best to put them in a comment below; I’ll post her answers for everyone to read, too. This is meant as an introduction to these two emotions, not a comprehensive analysis of them.

………………………………….

People use the word “guilt” more often than is appropriate. Improperly using the word “guilt” can result in unnecessary emotional distress and harsh self-criticism. The word “guilt” refers to something you did, something which you feel you shouldn’t have done because it was morally or legally wrong. But what if the experience you feel guilty about was not something you caused or had control over? Then you would feel regret, not guilt.

Here is an actual situation: Ann was referred by her family doctor for grief counseling. She was unable to cope with her persistent feelings of guilt related to her husband’s death several months prior. Bob was diagnosed with a terminal illness and he was bed-ridden. He needed constant care and attention which was mainly provided for by his wife. Bob was hospitalized for three weeks prior to his death. Ann was with him throughout that time as well.

On the day of Bob’s death, his wife left the hospital room to use the bathroom. When she returned to the room, the nurse told her that Bob had died in her absence. Ann was overcome with feelings of what she termed “guilt” and punished herself for not having been with Bob at the time of his death. For months she could not function and was preoccupied with thinking how terrible she was in being absent when her husband died. She mentally punished herself for breaking the vow she had made to herself to be with him when he died. Instead of focusing on the 99% of the time she had cared for him while he was ill, she focused on the last minutes he lived.

Why shouldn’t Ann feel guilty? Because she did not do anything that caused her husband’s death; she was not there. If Ann had asked the nurse whether it was “safe” for her to leave for a few minutes and the nurse had cautioned her that Bob could die at any time, and then Ann chose to leave, then she could justly experience guilt because she ignored information indicating he could die during the time she was away. In this alternate scenario, Ann had the personal responsibility for making the decision to go, she had control of making the decision that resulted in her absence, and could therefore justly experience feelings of guilt. As a counselor, if someone is justifiably guilty for an action, I would advise them to make a confession, offer an apology, take responsbility, and — if possible– make reparations.

By disproportionately magnifying these few minutes to overshadow all of the months of care Ann had given Bob, the result was that she could not forgive herself. After discussing the difference between regret and guilt, Ann came to see that there was, in fact, nothing to forgive. She understood that she was only responsible for her own actions; Bob didn’t die because she left the room. By reframing the circumstances of Bob’s death, Ann was better able to properly grieve her loss and move on afterwards.

Though Ann did not experience guilt, she did have regret, a universal experience. Regret refers to circumstances beyond one’s personal control. An unidentified author defined regret as “distress over a desire unfulfilled.” Regrets can pertain to decisions made concerning: education (not getting a degree), career (working at a job that offered good income but no personal satisfaction), marriage (married too young), raising children (being too permissive), medical decisions (sterilization), etc. These and other decisions can be considered mistakes.

As an emotional response to a distressing experience, the sound of the word “guilt” is harsher and more of a self-reproach than the word “regret.” If you say, “I feel so guilty” you should make sure that the deed and circumstances surrounding it actually warrant your feeling of guilt rather than regret.

Dr. Rita Bonchek has a Ph.D. in educational psychology. She spent twenty years in private practice.

Dr. Rita Bonchek has a Ph.D. in educational psychology. She spent twenty years in private practice.

January 16th, 2011 §

I never want people to feel sorry for me– I don’t feel sorry for myself. I feel lucky. I live a great life now; I’ve had a great life so far. I’ve learned a lot along the way and gotten stronger and stretched myself in ways I could not have predicted.

Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night panicked. The other night my worries about Tristan came to the surface. This week I have been working to get him additional physical and occupational therapy sessions from our town in preparation for kindergarten next year (if you don’t know about Tristan’s physical problems you can read about them here).

At 1:47 I lay in the dark wondering, “Who will care for this boy if something happened to me? What if I die — can anyone be his advocate the way I am?” I pondered that question for some time. I thought of the family in a documentary I watched two weeks ago called Monica and David. The film’s subjects have Down’s Syndrome and recently got married. They live in Florida with Monica’s parents in a condominium. Monica’s parents should be retired by now, enjoying their golden years. Instead, they have a full-time job caring for their adult daughter and her husband.

When I was watching the film I kept thinking about the same issue: who would help Monica and David if something catastrophic happened to Monica’s parents?

I realized that her parents have somehow come to terms with uncertainty, as we all must.

In graduate school my Ph.D. proposal dealt with management consultants and their claims of expertise. How did this group of professionals carve out a niche in the business market and claim that only they were qualified to objectively advise companies on what they should do to not only survive, but thrive? The certification of knowledge intrigued me. I never finished my dissertation, but many themes of study from years ago have stayed with me.

I never could have predicted that I’d be thinking about uncertainty in terms of cancer. I never could have known that those advising me on decisions would be oncologists and surgeons.

But just as Monica’s parents have learned to deal with that uncertainty, so must I.

Betty Rollin wrote that having cancer means being a little bit afraid at least some of the time. I know that’s true. But learning to manage uncertainty is a part of everyone’s life.