July 5th, 2013 §

Something happened to my brain when I heard the words “Your breast cancer has metastasized.” Suddenly, irreparably, it became a sieve. Surgical menopause without the option of hormone replacement seven years ago started the process. But mental anguish and immediate, lifelong chemotherapy been major contributors to my Swiss cheese mind.

Something happened to my brain when I heard the words “Your breast cancer has metastasized.” Suddenly, irreparably, it became a sieve. Surgical menopause without the option of hormone replacement seven years ago started the process. But mental anguish and immediate, lifelong chemotherapy been major contributors to my Swiss cheese mind.

I used to read a lot. People think of me as a reader. I am sorry to say I’ve become a fraud.

I love to support authors and their books. That has not changed. It never will.

But when it comes to what I’m actually reading (and finishing)… well, I have a confession to make: it’s not much in the past nine months.

My mind jumps all over the place. It simultaneously wants quiet but is restless. It craves nothingness and distraction. It is hard for me to sustain long conversations; I find them exhausting now. This is one reason Twitter has remained such a wonderful social medium for me; it is defined by short chats that can be stopped and started at will.

When it comes to reading, however, I am having trouble. I hope this ability will return. I spend my focused time writing when I can. Even then, as readers here know, I almost always write brief pieces, expressing thoughts in as few words as possible.

When I was first diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent chemo in 2007 I didn’t read either. I hear from so many people that this is how they felt, too. Those who are newly-diagnosed think they will spend their time catching up on books they want to read during chemotherapy or after surgery. It just rarely happens: either your brain is in a fog or you feel rotten. When you feel good, you want to get out and do things with your family and/or friends.

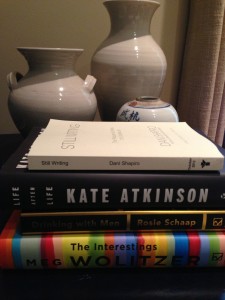

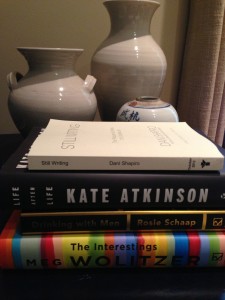

My current stack of “am reading” and “to be read” is shown in the photo above: books by Dani Shapiro (am reading), Kate Atkinson, Rosie Schaap, and Meg Wolitzer (to be read). I’ve cleared out shelves and shelves of books that I know I won’t get to and given these treasures away. It really made me sad to see so many books there, mocking my isolation: tangible reminders of things I will leave undone. And yet, I saved a bookcase or two of books I still want to read. I won’t give up hope completely.

So now I turn it to you, readers: Do you go through phases of reading? What have you noticed about your reading habits when you had bad news? Health issues? Medical treatment of some kind?

On the flip side, what happened to your reading habits after happy events? I didn’t read after the birth of each of my children: middle of the night feedings were accompanied by nodding off, not turning pages of a book. I’m not an audio book person, I should specify. I know how wonderful this format can be, it just doesn’t work for me. I either fall asleep (chemo fatigue and the sound of someone reading to me… isn’t that how we prime our children for bedtime, after all?) or my mind does its trademark wandering and I have to keep rewinding the story.

The beautiful thing about a book is that it endures. It will wait for you. Like a good friend, when you are finally ready, it will share itself with you.

January 6th, 2013 §

I love books. I love reading. I love the power of words to transport us, change us, connect us.

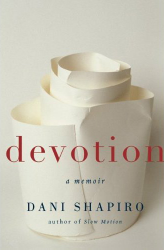

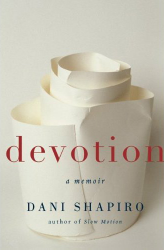

One author I admire in every way — personally and professionally — is Dani Shapiro. This post from 2011 doesn’t talk about the details of her latest book Devotion, but I still want to repost it not only to encourage you to read the book for yourself but also because I think it’s intersting to think about how we interact with what we read. Dani has a new book coming out called Still Writing. There isn’t anyone to me who can capture the art of writing the way she can.

…………………………….

I’m not the kind of person who reads books twice. My husband wears down the fibers in the covers of some of his books, corners frayed by his hands as he holds and bends the written pages. Me? I barely have enough time to read a book once. My attention span is short, my free time small. With three children and a house to take care of there just doesn’t seem to be time to do everything I want.

This morning I awoke knowing what I wanted to do. I wanted to re-read sections of Dani Shapiro‘s second memoir, Devotion. About twenty pages into it I realized I was literally itching to do something: write in the book. I hadn’t allowed myself to do that the first time. Lately I had felt that my books (especially ones written by people I knew in person or on Twitter, even moreso if signed by the author) should remain pristine. I have eschewed e-readers in every form for this very reason… typing notes in margins is not as satisfying as using colored ink to have my interactive conversation with the author. Sometimes exclamation points or “YES!” will interrupt the creamy expanse of the margin, but more often than that my graduate school training has led me to issue challenges to the author. Questions that start with “But what about…” or the challenging, “Does not take into account…” are what you will find in my books. As I try to process what the author says I imagine I am conversing with them. And, in fact, I am; writers write to start a conversation with the reader. If all the reader does is absorb without processing I think the author might be disappointed.

As I started Dani’s book this morning I realized the pristine condition of my hardcover was getting in my way. I needed to interact with it to really get the full benefit of her words. It seems the right thing to do. Only pages in to this second time through, I was already finding questions I want to ask her. I was, after all, a different person by my second reading. I was coming to the book with more experiences, different concerns and thoughts than I previously had. I came to the book with many of the same questions Dani herself was seeking to answer when she started writing. I realized that in the same way she had made sense of what happened to her by writing, I needed to do that too. Writing in the margins was my microcosm of that experience; without “talking back” I had missed a lot of the beauty and significance of her words.

I already feel myself digesting her words in a different way. The same way I cannot experience major events in my life without writing I realized this morning I cannot make sense of words without reacting. As my memory has declined and my mental capacities have suffered over the past few years I can’t rely on them to retain the memories of the sentences and paragraphs that have spoken to me. I need to wrestle with them, tease them out, formulate responses.

My book will be riddled with ink by the time I am done. But I realized today that is precisely as it should be. I think Dani would like that. I think it means I’m learning.

January 13th, 2012 §

Today’s post is one of the rare ones that discusses a book I’ve read. I’ve previously written about Dani Shapiro’s Devotion and Katie Rosman’s If You Knew Suzy. Today I share some thoughts I have after reading Darin Strauss’s memoir Half a Life. The book won The National Book Critics’ Circle Award. If you’d like to hear some excerpts, you can listen to an NPR podcast here. It’s gripping radio.

Today’s post is one of the rare ones that discusses a book I’ve read. I’ve previously written about Dani Shapiro’s Devotion and Katie Rosman’s If You Knew Suzy. Today I share some thoughts I have after reading Darin Strauss’s memoir Half a Life. The book won The National Book Critics’ Circle Award. If you’d like to hear some excerpts, you can listen to an NPR podcast here. It’s gripping radio.

I’m not a book reviewer, and this post isn’t a review; I consider it more of a response piece. Half a Life touched me in many ways and I still find myself thinking about it weeks after closing the cover.

One reason I like to write about books is because our reading of them is so personal. We bring our own experiences to bear on an author’s words; passages which seem to have been written just for us may go unnoticed or unappreciated by others. Reading is a solitary activity, yet we are a community of readers. I welcome comments about this book and/or the general topics.

………………………………

I think the Zilke family is lucky.

You might think that is a crazy statement if you know the story of how more than twenty years ago their teenage daughter Celine suddenly jerked her bicycle across two lanes of traffic and into the immediate path of fellow classmate Darin Strauss’s car. He couldn’t hit the brake in time; in truth, there was no time. Whether or not Celine intended to die on that day remains a mystery, we will never know what caused her to swerve. But die she did, with Darin behind the wheel, on that road, on that day, at that moment.

It wasn’t Darin’s fault; it could have been anyone in that particular place at that particular time. If his shoe had been untied and he’d taken a moment to tie it, if he’d forgotten his wallet upstairs, if he’d decided to use the bathroom one more time before heading out with his friends for a round of mini-golf, if… well, if anything… things might have been different.

If games are so common with grief: If only _____, things would be different. We create counterfactuals in our minds, imagining an alternate reality to the one that we just don’t want to accept. We hide away our truth, conceal the reality of pain. Darin did this for half of his life. For all that time he felt the pressure to live his life for two people; to make his life special, meaningful, and worthy of the fact that he lived while a schoolmate did not. Although Celine’s family originally absolved him of blame (and he was never criminally charged after the accident), they later sued him, settling out of court.

So why do I think they are they lucky?

Well, you have to know a little bit about me, and about my grief. If you’re a regular reader you know that my mother-in-law was killed in a car crash (I don’t ever call it an accident, unlike Darin’s case) when a man was driving in the wrong lane on a Wyoming highway in 2009. He was trying to pass an oversized load and was alongside that load at highway speed around a curve. His view obscured by the load, he didn’t know there was a car carrying my inlaws directly in front of him. The newspaper account appears here.

My mother-in-law was killed instantly; my father-in-law, seriously injured. The driver of the other car was charged with the misdemeanor charge of vehicular homicide and later sentenced to 90 days in jail. My account of that heartwrenching day and my visit to the crash site appears here.

Bruce Carter, the man who killed Barbara, didn’t say a word at the sentencing. He never said he was sorry.

I wonder if he thinks about her. I wonder if he thinks about us, the ones left behind.

I think the Zilkes are lucky because now they know. They know Strauss’s grief, some of his thoughts, his emotional shift from guilt to regret. Celine’s parents don’t need to worry, as I do, that their loved one has been forgotten by the person who took his/her life. Strauss’s agonizingly honest description of his thoughts about his actions and their aftermath resonate because they are so well-analyzed. Though the loss of a child in an accident is difficult, perhaps knowing that Celine’s life became a litmus test for so many events in Strauss’s own life would be a speck of reassurance. As Strauss grows older, Celine’s memory becomes his partner in a 3-legged race, bound together, their lives pulled awkwardly into tandem. I think the worst thing is to be forgotten. With this analysis of his life in the last 20 years, Strauss documents the changing nature of his grief.

……………………….

The theme of living one’s life for two people– of making his life “count” for two after the accident is one that is especially intriguing. Eventually Darin realizes this is impossible. As a high schooler he had reflexively promised Celine’s mother that he would make his life count for two, but this is the knee-jerk automatic response of a young person agreeing with something he doesn’t understand. Just like the ineffective shrink who pigeonholed Darin’s responses (ultimately making therapy a worthless endeavor), Celine’s mother obtained the answer she wanted from a person unable to fully understand what he was agreeing to. In a similar fashion, when a child dies, a sibling often feels he/she now has to carry the added weight of the unfinished life of the deceased family member. This psychological burden can be overwhelming.

We become responsible for others in many ways– as their friends, siblings, children, and especially as parents– but we do not truly understand these obligations when we first enter these relationships, most certainly when we are young. Growing into the recognition and acceptance of these responsibilities is part of the process. In so many ways we are wholly unprepared for the roles we step into both personally and professionally.

Others had been quick to forgive Darin– to tell him it couldn’t have happened any other way. Like the legal standard of the “reasonable man,” Darin had passed the test; there was nothing he could have done to avoid hitting her. However, his own timetable of forgiveness was much longer. While others instantly granted it to him, it took twenty years for Darin to forgive himself.

………………………

Regret and guilt play a large role in Strauss’s book, I did often disagree with his frequent interchangeable use of the terms. Regular readers may remember the guest post my mother (a psychologist specializing in grief and loss, death and dying) wrote about the difference between guilt and regret (full post here). I have certainly come to accept those distinctions and to use them accordingly:

People use the word “guilt” more often than is appropriate. Improperly using the word “guilt” can result in unnecessary emotional distress and harsh self-criticism. The word “guilt” refers to something you did, something which you feel you shouldn’t have done because it was morally or legally wrong. But what if the experience you feel guilty about was not something you caused or had control over? Then you would feel regret, not guilt.

Througout the book Strauss uses the terms interchangeably. He ends up with a painful stomach disorder requiring surgery. He later suffers from IBS and then CPPS (chronic pelvic pain syndrome) summarizing, “That’s the force of guilt for you.” I’d argue that it’s regret he feels; the accident wasn’t his fault. I wonder if Strauss would describe the book as I do, one which documents the evolution from guilt to regret; a journey toward making peace with the fact that things couldn’t have been different on that day.

I couldn’t help but wonder if counseling could have helped him see his actions in the proper light and helped to relieve some of this literal gut-eating self-criticism he’d been experiencing for years. At various points, Strauss believes Celine may have committed suicide, there are clues that this may have been the case. In the end, the only emotion Strauss is justified in feeling is regret; he writes, “Regret doesn’t budge things; it seems crazy that the force of all that human want can’t amend a moment, can’t even stir a pebble.”

Given my upbringing, I couldn’t help but be bothered by the lack of good psychological support for Strauss after the accident– could an insightful therapist trained in grief counseling have helped him negotiate some these feelings? Strauss says in a footnote, “I’d started going to therapy… though not (I really don’t think) as a response to the accident. I’d gone with pretty boilerplate stuff: your typical mid-thirties complaints… my therapy attempts had always been near-misses, fizz-outs if not outright failures.” A psychologist specializing in grief would have certainly been able to show that while Strauss may not have himself seen that he was seeking therapy as a response to the accident, it certainly could not be removed from his problems. While the problems in his thirties may have been boilerplate, the accident which haunted him for twenty years until that point was not.

……………………….

Writing about grief, regret, shame, and inner turmoil can be difficult. By their very nature our most personal and private thoughts can be difficult to express. However, they can also be the most rewarding to document, for these are challenges most people face at some point in their lives. The road maps we have for navigating life’s challenges are some combination of our own instincts, observations of others, and advice along the way.

I would think Strauss has heard hundreds, if not thousands, of stories since he finally began sharing his own. Tragedy invites sharing, camaraderie. I have found a similar experience with cancer; there is a natural tendency for others to connect and say “I have been there too.”

………………………….

Strauss is now a father. I wonder how Celine’s death will impact his next twenty years. Will he be more safety-conscious? What will it be like the first time his sons drive a car? Ride a bike on a busy street? How will he navigate parenthood differently because of this experience? And what are the triggers now for making him think of Celine? There must certainly be a pattern to those. Perhaps because therapy was ineffective in his youth, I was left wondering if parenthood will cause some of these unresolved emotional landmines to crop up yet again.

While time has a way of allowing us to move into a different stage of grief where we can go through minutes, hours, and days without being consumed with emotion, the feelings are always there, just below the surface, ready to rise at a moment’s notice. We can’t possibly always know what might trigger the flood, but it will come.

I started this post saying the Zilkes are lucky; they have a window into the mind of the person who accidentally killed their child. My own unanswered questions about Barbara’s death certainly affected my reading of this book. If I can’t have my own answers, I wanted to read Strauss’s. The truth is that we have to find our own answers, our own ways of weaving experiences into the tapestry of our lives so that we are resilient for what is yet to come.

I really enjoyed reading this book and grappling with some of these difficult questions as I read. The themes of death, regret, perseverance, responsibility, and decision-making are endlesslessly fascinating to me.

November 20th, 2011 §

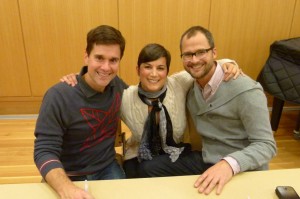

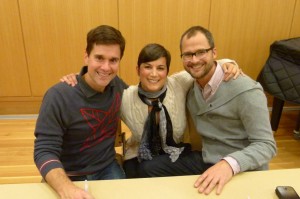

Last week Darien was lucky enough to have the Fabulous Beekman Boys (Dr. Brent Ridge and Josh Kilmer-Purcell) come to do a book signing at the Darien Library. My friend Aimee did a great blog post with more pictures on her own site but I wanted to share the picture she took of the three of us.

I love the photo! Brent and Josh have a farm in Sharon Springs, NY and their business is based there too. When they found and fell in love with the historic hotel/farm, the two men rearranged their lives to make their dream of owning a working farm come true. Brent left his medical practice in geriatrics to be at the farm full-time. Josh divides his time between the farm and working in advertisting and an author. They also had a TV show on Planet Green for a few seasons which chronicled their time getting the farm established. It’s wonderful and I always enjoyed watching it.

Josh has written two memoirs I Am Not Myself These Days (which is about his life as a drag queen) and the book about their farm, The Bucolic Plague. They have a new cookbook (The Beekman 1802 Heirloom Cookbook) which I love because the recipes are very simple and take advantage of foods that are in season. Every detail of the book is beautiful from the sewn pages to the cover which is designed to look like cheese cloth (their handmade cheese called Blaak is a favorite of mine. They make it in limited edition each year; its black ash rind is beautiful).

Josh and Brent were warm, entertaining, and funny… just as I thought (hoped) they would be. They are very involved with their fans on Twitter and Facebook and work very hard not only at the farm but also now on tour. Josh had just gotten off the train in Darien after a full day of work at his office in the city. They are tireless advocates for small town businesses and the craftspeople who make fine wares.

You can find them at www.beekman1802.com

here is a link to Aimee’s post about the evening: The Fabulous Beekman Boys

July 5th, 2011 §

Last summer I wrote the following piece about an upsetting interaction I had with a bookseller. It remains one of the posts that readers mention and still ask me about. The topic of children and death must be a touchy subject for most. I guess because I grew up with a mother who was a psychologist specializing in these topics I have never felt uncomfortable talking about them. Let me know what you think.

……………………………….

June 23, 2010

School is out for my three children. At ages 11, 8, and 4, the days are a hodgepodge of activities to allow them relaxing time at home with each other and some physical activity each day. No matter what their summer plans hold (sleepaway camp for 2 of them later this summer), I always make sure they each have a stack of books they are excited to read. Each night they go up to their rooms for at least 30 minutes before bedtime to read.

Yesterday we took a trip to my favorite independent bookstore. The tiny, jam-packed store has many employees who know and love books working there (all women, it seems). The children’s section is brimming with wonderful books for all ages. My favorite thing to do is bring the older children there and let them chat with a bookseller, telling what they’ve just read and whether they liked it or not. The clerks then can make suggestions about what the kids might like to buy/read next.

When we walked in it was apparent my favorite person was not there to help us. Another woman offered, and off we went to the back room. “What have you just read that you liked?” she asked my 11 year-old daughter. “Elsewhere,” (by Gabrielle Zevin) she answered. The woman immediately snapped, “That’s too old for you. It has death in it,” she said. She looked at me quizzically, silently chastising me for my daughter’s book choice.

“I don’t mind that she reads about death,” I said.

“I loved that book… it was so good!” Paige implored.

“It’s not appropriate for a 7th grader,” the woman persisted.

“I think it’s how the subject is handled,” I said. “We talk openly about death and illness in our house, and my daughter is obviously comfortable reading about it,” I pushed.

The subject was over. She was not going to recommend any books that had to do with the death of a teenager or what happens to that character after she dies. And so, she moved on to other books and topics. Eventually, we found a lovely stack for Paige to dive into.

As soon as we left I talked to Paige about what had happened: how the bookseller had steered her away from reading about death and pushed her to “lighter fare.” I told her that I disagreed with this tactic, and fundamentally think it reinforces a fear of death and discomfort with talking about the subject.

While I believe that a teenager’s obsession with death can be a signal of some larger emotional problem, I do not think that reading novels where the main character dies is inherently a bad idea for a mature reader. After all, so many of even young children’s favorite characters in television and movies have absent/dead parents; Bambi, Max and Ruby, and countless others have significant adults missing from their lives.

I don’t believe in forcing children to deal with the topic of death in reading until they are ready. I do believe parents are the best arbiters of what information and topics are appropriate for their children. But if a child is comfortable in reading books where a character dies, I believe it’s healthy for the child to do so. As a springboard for an honest conversation about death, it can even be extremely useful in beginning to have conversations at home about it.

Paige’s grandmother was killed instantly in a car crash in the fall of 2009. She learned that the death of a loved one can greet us at any time, whether we are prepared for it or not. By trying to steer my mature child away from the topic, the salesperson contributed to the emotional shielding that makes death a topic that so many individuals (including children) have difficulty thinking and talking about.

November 23rd, 2010 §

Originally published June 24, 2010

There comes a point in your life when you realize that your parents are people too. Not just chaffeurs, laundresses, baseball-catchers, etc.– but people. And when that happens, it is a lightbulb moment, a moment in which a parent’s humanity, flaws, and individuality come into focus.

If you are lucky, like I am, you get a window into that world via an adult relationship with your parents. In this domain you start to learn more about them; you see them through the eyes of their friends, their employer, their spouse, and their other children.

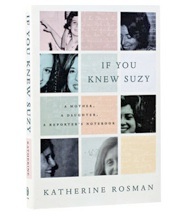

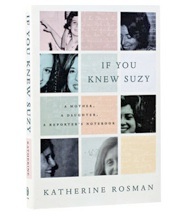

Yesterday I sat transfixed reading Katherine Rosman’s book If You Knew Suzy: A Mother, A Daughter, A Reporter’s Notebook cover to cover. The book arrived at noon and at 11:00 last night I shut the back cover and went to sleep. But by the middle of the night I was up again, thinking about it.

I had read an excerpt of the book in a magazine and had already been following Katie on Twitter. I knew this was going to be a powerful book for me, and I was right. Katie is a columnist for The Wall Street Journal and went on a mission to learn about her mother after her mother died (on today’s very date in 2005) from lung cancer. In an attempt to construct a completed puzzle of who her mother was, Katie travels around the country to talk with those who knew her mother: a golf caddy, some of her Pilates students, her doctors, and even people who interacted with Suzy via Ebay when she started buying up decorative glass after her diagnosis.

Katie learns a lot about her mother; she is able to round out the picture of who her mother was as a friend, an inspiration, a wife, a mother, a strong and humorous woman with an intense, fighting spirit. These revelations sit amidst the narrative of Katie’s experience watching her mother going through treatment in both Arizona and New York, ultimately dying at home one night while Katie and some family members are asleep in another room.

I teared up many times during my afternoon getting to know not only Suzy, but also Katie and her sister Lizzie. There were so many parts of the book that affected me. The main themes that really had the mental gears going were those of fear, regret, control, and wonder.

I fear that what happened to Suzy will happen to me:

my cancer will return.

I will have to leave the ones I love.

I will go “unknown.”

My children and my spouse will have to care for me.

My needs will impinge on their worlds.

The day-to-day caretaking will overshadow my life, and who I was.

I will die before I have done all that I want to do, see all that I want to see.

As I read the book I realized the tribute Katie has created to her mother. As a mother of three children myself, I am so sad that Suzy did not live to see this accomplishment (of course, it was Suzy’s death that spurred the project, so it is an inherent Catch-22). Suzy loved to brag about Katie’s accomplishments; I can only imagine if she could have walked around her daily life bragging that her daughter had written a book about her… and a loving one at that.

Rosman has not been without critics as she went on this fact-finding mission in true reporter-style. One dinner party guest she talked with said, ” … you really have no way of knowing what, if anything, any of your discoveries signify.” True: I wondered as others have, where Suzy’s dearest friends were… but where is the mystery in that? To me, Rosman’s book is “significant” (in the words of the guest) because it shows how it is often those with whom we are only tangentially connected, those with whom we may have a unidimensional relationship (a golf caddy, an Ebay seller, a Pilates student) may be the ones we confide in the most. For example, while Katie was researching, she found that her mother had talked with relative strangers about her fear of dying, but rarely (if ever) had extended conversations about the topic with her own children.

It’s precisely the fact that some people find it easier to tell the stranger next to them on the airplane things that they conceal from their own family that makes Katie’s story so accessible. What do her discoveries signify? For me it was less about the details Katie learned about her mother. For me, the story of her mother’s death, the process of dying, the resilient spirit that refuses to give in, the ways in which our health care system and doctors think about and react to patients’ physical and emotional needs– all of these are significant. The things left unsaid as a woman dies of cancer, the people she leaves behind who mourn her loss, the way one person can affect the lives of others in a unique way… these are things that are “significant.”

I woke up in the middle of the night thinking about the book. My head spun with all of the emotions it raised in me. I think that part of the reason writing has become so important to me is precisely because I do realize that we can die at any moment. And if you don’t have an author in the family who might undertake an enormous project as Katie did, where will that explanation of who you were — what you thought — come from?

Is my writing an extension of my desire to control things when cancer has taken away so much of this ability?

Is part of the reason I write an attempt to document my thoughts, my perspective for after I am gone… am I, in a smaller way, trying to do for myself what Katie did for her mother?

If I don’t do it, who will do it for me?

And in my odd way of thinking, am I trying to save anyone the considerable effort of having to work to figure out who I was– deep down?

My blog has the title “You’d Never Know”: I am telling you things about myself, my worldview, and my life, that you would otherwise have no knowledge of. One of the things people say to me all the time is, “You’d never know to look at you that you had cancer.” After hearing this comment repeatedly I realized that much of our lives are like that:

If we don’t tell someone — share our feelings and experiences — are our lives the proverbial trees falling (unheard) in the forest?

What if you die without being truly understood?

Would that be a life wasted?

If you don’t say things for yourself can you count on others to express them for you?

Further, can anyone really know anyone else in her entirety?

After a loved one dies, there always seems to be at least one mystery person: an individual contacts the family by email, phone, or in person to say, “I knew your loved one: this is how I knew her, this is what I remember about her, and this is what she meant to me.” I know that this happened when Barbara (my beloved mother-in-law) died suddenly last fall. There are stories to be told, memories to be shared. The living gain knowledge about their loved one. Most often, I think families find these insights comforting and informative.

Katie did the work: she’s made a tribute to her mother that will endure not only in its documentation of the person her mother was (and she was quite a character!) but also in sharing her with all of us. Even after her death, Suzy has the lovely ability to inspire, to entertain, to be present.

I could talk more about the book, Katie’s wonderful writing, and cancer, but I would rather you read it for yourself. I’m still processing it all, making sense of this disease and how it affects families, and being sad that Katie’s children didn’t get to know their grandmother. Katie did have the joy of telling her mother she was pregnant with her first child, but Suzy did not live long enough to see her grandson born. In a heartwarming gesture, Katie names her son Ariel, derived from Suzy’s Hebrew name Ariella Chaya.

I thank Katie for sharing her mother with me, with us. As a writer I learned a lot from reading this book. I’ve said many times recently that “we don’t need another memoir.” I was wrong. That’s like saying, “I don’t need to meet anyone new. I don’t need another friend.” Truth is, there are many special people. Katie and Suzy Rosman are two of them.

Something happened to my brain when I heard the words “Your breast cancer has metastasized.” Suddenly, irreparably, it became a sieve. Surgical menopause without the option of hormone replacement seven years ago started the process. But mental anguish and immediate, lifelong chemotherapy been major contributors to my Swiss cheese mind.

Something happened to my brain when I heard the words “Your breast cancer has metastasized.” Suddenly, irreparably, it became a sieve. Surgical menopause without the option of hormone replacement seven years ago started the process. But mental anguish and immediate, lifelong chemotherapy been major contributors to my Swiss cheese mind.

Link to Twitter

Link to Twitter