May 3rd, 2011 §

There isn’t one right way to react to loss. And the thing about grief? It’ll sneak up on you precisely when you’re not looking.

This morning I attended a memorial service for a 38 year-old mother of two. She died of complications from leukemia, leaving a loving husband and two children behind. We were connected by a shared friend and a diagnosis of cancer.

When Kellie was diagnosed fifteen months ago and learned she needed to have chemotherapy I offered her my scarves. I had an extensive collection from my months spent without hair and had been serially loaning them out to friends after my hair grew back. After they’d covered my head, they’d gone to a friend’s sister in Colorado who had breast cancer. Then they went to a friend down the street who also had breast cancer. The fourth head they touched was Kellie’s.

During that time I had to deny others the use of the collection. I know too many women who’ve had cancer, I thought. There isn’t a break in between their tours of duty. The scarves don’t rest, they just keep traveling.

Perhaps some might find it icky to wear a scarf of someone else’s. That never seemed an issue for my friends. In fact, their softness from being washed so often was a bonus; heads are sensitive when hair comes out and the softer the cotton is, the better.

Kellie had those scarves for a long time. Her own fiery red hair was long gone; my scarves were a poor substitute for that ginger hair of hers. I like the thought of her having something comforting and cheery to cover her head during some of those difficult days though.

After the service today the guests stood talking over coffee and tea and far too many sandwiches and baked goods. Unprompted, our mutual friend assured me the scarves were safe and would be returned soon. I know when the stack comes back I’ll touch the scarves longingly, wishing Kellie were delivering them herself.

I’m overwhelmed today with emotions… sadness at the second Mother’s Day without my beloved mother-in-law, anger at cancer for claiming another young mother, frustration that oncology is often an art more than a science, worry that it will happen to me.

I just need to think. I just need to cry. I just need to remember. I just need to live.

May 1st, 2011 §

In the weeks before my surgery, I looked at pictures of double mastectomy patients on the Internet. I Googled “bilateral mastectomy images before and after” thinking I was doing research. I thought I was preparing myself for what was coming.

In reality I was trying to scare myself. I wanted to see if I could handle the worst; if I could, I would be ready. My reaction to those images would be my litmus test.

Some of the pictures were horrific. I sat transfixed. I looked. I sobbed. I saw scarred, bizarre, transformed bodies and couldn’t believe that was going to be my body.

Days later, when I met my surgeon for my pre-op appointment he said, “From now on, don’t look at pictures on the Internet. If you want to see before and after pictures, ask me– look at ones in my office. You can’t look at random pictures and think that’s necessarily what you are going to look like.”

All I could do was duck my head in an admission of guilt. How did he know what I’d done? I realized how he knew: other women must do this. Other women must have made this mistake.

The aftermath is terrible to me though not in the ways I’d anticipated. I have no sensation in most of my chest. I never will.

A major erogenous zone has been completely taken away from me. Yes, I have new nipples constructed, but they have no feeling in them; they are completely cosmetic. The entire reconstruction looks great but I can’t feel any of it. It does help me psychologically beyond measure to have had these procedures though.

Here I sit, two gel-filled silicone shells inside my body simulating the biologically feminine body parts I should have. And sometimes that thought is disturbing.

To be clear: I don’t regret having them put in. I’ve never regretted that. It was a decision I made, and made deliberately. I knew that reconstructing my breasts was the right decision for me. I’m getting used to them– I’m almost there.

I definitely don’t remember what my breasts looked like before. I only remember these.

I once asked my plastic surgeon to see my “before” pictures a year or two after my reconstruction was over. You know what? My “before” breasts didn’t look so great. In my mind they did.

In my mind, everything about my life before cancer was better.

But that’s not the truth.

My mind distorts the memory of my body before cancer. Then forgets it.

My mind distorts the memory of my life before cancer. Then forgets it.

With time, I can get used to a new self.

It’s like catching my reflection in the mirror: only lately do I recognize the person staring back at me.

For over a year the new hair threw me. It’s darker than I remember it being before it fell out. It’s shorter than it was before, too.

And the look in my eyes? That’s different also.

I just don’t recognize myself some days.

Sounds like a cliché if you haven’t lived it.

But it’s true.

April 15, 2009

April 30th, 2011 §

What does it mean to “be an inspiration”? A few people have said that to me recently: I am an inspiration. At first I laugh. I guess I’m an inspiration because I’m still alive. Maybe that’s enough.

What’s inspirational about me? Trust me, I’m not searching for platitudes here. I’m trying to get at “what makes someone an inspiration” and why do people think I and so many other breast cancer survivors qualify? There’s definitely more than one day’s blog in this question.

Is it being a mother and worrying about your children more than yourself? No. That’s what every mother does.

Is it summoning strength to confront chemo when it’s your greatest fear?

Is it putting a smile on your face when you are crumbling inside?

Is it speaking the words, “I have cancer” to your children, your friends, your husband, your parents, your in-laws, your brother, and all of the people in your life enough times that eventually it starts to sound normal?

Is “inspirational” when you offer to show your post-mastectomy body to women so that they will know the results just aren’t as scary as they are thinking they will be?

Is it answering everything and anything people want to know?

Is it putting words and feelings in black on white?

The essence of inspiration is being strong.

When you least want to be.

When you are faking it.

Strength.

When you lack it.

When you have to dig deep for it.

When your kids need dinner and you want to vomit from the chemo.

When you are too weak to climb the stairs.

And you don’t think you can get through another day.

Or hour.

Or minute.

Or second.

And you just want the pain to end.

Somehow.

Some way.

Any way.

Just have it go away.

When your pride is gone.

Dignity is gone.

All of it.

Being inspirational means being tough.

It means feeling rotten but not wanting others to.

It means wanting to put others at ease with how you are doing.

It means being a lightning rod for everything bad.

A catalyst for everything good.

A spark.

A resource.

A friend.

A wife.

A lover.

A mother.

A daughter.

It means telling your parents you feel okay when you don’t.

A little fib so they will go home and get some rest for the week.

Take some time off for themselves before they come back in 8 days and do it all over again.

A break so they don’t have to see their little girl suffer anymore

Because 6 days in a row is enough.

For anyone.

Because looking good makes others feel better about how you are doing.

So you put makeup on.

And dress well.

And put a big smile on your face.

So they will think you are feeling good.

And when you switch the topic of conversation, they will go along with it–

They will believe you when you say you are feeling better.

Okay, so maybe I am inspirational. I don’t call it inspirational. I can only admit to the smaller things. The micro things. Inspirational sounds big. Important. It’s hard to accept that one.

But I think I’m convinced.

The reason I’m going to finally concede is that I just realized something:

That was my goal.

Except I wasn’t calling it that.

I was just calling it doing it right.

I was calling it setting an example.

I was trying to show my family, especially my daughter, how you can tackle an obstacle– a big one.

I was just doing my job.

June 15, 2009

April 28th, 2011 §

I almost stole it: the tape measure with the purple finger prints.

After all, my surgeon had left it in my room by accident. After he had marked me with his purple pen and left my room on his way to get ready for my surgery, he left it sitting on the counter by the sink. In my nervousness and tranquilized haze I didn’t see it until after he’d left. I figured I shouldn’t hold onto it as I was wheeled in (“Who knows what germs lurk in tape measures!” I thought), and that if I gave it to a nurse it might get misplaced. So I shoved it in my bag of personal belongings knowing I’d be in for an office visit shortly after surgery.

I actually forgot about it during the days I was home after my two-day hospital stay. The drugs, the pain, the shock of my breasts gone and numb chest filled with temporary tissue expanders were all I could think about.

I forgot all about it as I was shuttled around for weeks unable to drive. I wasn’t living my normal life, my normal routine. I wasn’t carrying my purse and keys daily. I was living in pajamas and constantly trying to adjust to a new body once the drains were removed.

Then while I was looking for my keys a few weeks after my operation I saw it: the tape measure.

The yellow fabric one with the purple fingerprints up and down its sides.

The one.

The one that had measured and determined where my body was to be cut.

It was there in my bag.

There wasn’t anything particularly special about its practicality; it was just a tape measure.

Just like the ones I have sitting around with all of the odds and ends that inhabit kitchen drawers.

But that doesn’t capture the social meaning of it.

It wasn’t just any tape measure. It was mine.

But it wasn’t just mine, I argued with myself—it wasn’t a personal momento for me.

For a moment or two I wanted it.

I needed it,

as if to remind myself what had been,

of what I had been.

It wasn’t mine, I thought– it was his.

But more than that, it was theirs; it was ours… the other women who had needed it.

Now I was one of them. It was a shared history we had: strangers who had endured the same surgery, whose faces and names I would not know.

We were bound together by this object which had literally touched all of us.

And then I realized it was my responsibility to give it back.

Not for the obvious reason that it didn’t belong to me.

But as usual, I thought of the other women: the ones who didn’t even know they had cancer,

the ones who were going about their normal lives that day, and in the days ahead, only days or weeks or months from learning the life-altering news that would change their lives.

I felt giving back the tape measure would be my way of being bound to them, of saying “I know what you have ahead of you. I’ve come from there, and we are in it together.”

And so when I went to one of my office visits, I took it out of my bag and casually handed it to my surgeon. “You forgot this in my room when I had my surgery,” I said. He thanked me and said “I wondered where it had gone to.”

Little did he know the journey it had taken.

April 24th, 2011 §

I have a friend — a good friend. We’ve known each other for a long time. When I was going through chemotherapy for breast cancer, however, she wasn’t my most sympathetic friend. One of her typical reactions when I would talk about the bottomless fear of cancer recurrence that was swallowing me up was, “Well, I guess you’ll just have to get used to it.”

This was not really stellar support in my book; I think she could have done better. In my mind, because a close family member of hers had cancer in her past, she was not a stranger to its emotional component. Perhaps if no one in her life had ever had cancer I might have been more forgiving. Her relative was doing well, still in remission many years after her initial diagnosis. I mentally wrestled with myself: was I being too hard on a friend? After all, my emotions were on a rollercoaster. Things that didn’t bother me one day would infuriate me the next. Was I actually trying to let her off the hook for not emotionally supporting me? Was I excusing bad behavior? If those who have no experience with cancer shy away from those who are ill and those who have experience do so as well (if the memories are too painful to think about) then who is left to support you when needed? I couldn’t decide if I was expecting too much; maybe I was setting my friend up for failure.

Many times on the phone with her during my months on chemo as she proceeded to rant about the problems in her life and the ways in which things were not going her way, I wanted to point out to her how my life was “doing me wrong” in a bigger way.

Looking back, I wanted to trump her woe.

Lately, she has been having some medical issues of her own. Nothing permanent or relatively serious, but annoying and painful. For the last few weeks she has had some pain that is “excruciating.” She’s abroad this week, on vacation with her family. The pain, I guess, was not enough to keep her from that. While she has complained about her pain, her appointments, her problems for the last few weeks, I’ve really been holding back. I’ve really had to fight the part of me that wants to once again lash out.

“I guess you will just have to deal with it,” I want to say just like she did to me.

“I guess it’s not bad enough you can’t take your European vacation,” I want to say in a childish retort.

I want to trump her pain.

I want to wave the cancer card. Cancer trumps her issue, chemo trumps the discomfort she’s got.

Four years ago I found it almost intolerable that she should complain to me about the small things that were bugging her… the traffic on the way to school dropoff and how “inconvenient” her child’s schedules were. The way she had to take her child to the doctor twice in one week to check out an ear infection. How repairmen were keeping her waiting.

These things get sympathy from me under normal circumstances; these are things that bug me in my own daily life.

But not then.

While I kept silent then,

put it behind me then,

this latest round of friendship injustice just makes that time raw once more.

It brings that anger back.

My fear is that every time my friend has a hard time from now on, I am going to again have that feeling that she let me down when I needed her. I thought I had moved past it, but I guess not.

I don’t want it to get in the way of our friendship.

Maybe someone who wasn’t there for me then can’t really be a friend now.

Maybe some lessons can’t be learned until you go through them for yourself.

Maybe she can’t know how her responses hurt me unless she experiences it for herself someday.

The thing is: I don’t wish it on her.

People have different strengths.

We shouldn’t expect a person to be good at everything–

To fulfill all of our needs, all the time.

Extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures.

Maybe that’s true of forgiveness too.

April 13th, 2011 §

It seems like you can’t rank anguish. You shouldn’t be able to “out-suffer” someone. How do you quantify misery?

And yet, somehow we do.

“My problems are nowhere near as bad as yours.”

“I feel terrible complaining to you about it when you are going through so much yourself.”

I hear these types of comments all the time.

I make these types of comments all the time.

Placing ourselves in a hierarchy of pain and suffering serves to ground us; no matter how bad our situation is, there’s comfort in knowing there’s always someone who has it worse. Like being on a really, really long line at the movies or at the check-in at the airport, as long as there is someone behind you, it somehow seems better.

Hospitals use a pain rating scale: “On a scale of 1 to 10, how bad is your pain?” I was very intrigued when my son Colin was in the hospital for a week with a ruptured appendix and they asked him to rate his pain. At the time he was 5 years old and didn’t understand what they wanted him to do. He didn’t understand the concept of comparing one level of pain to another: it hurt… that’s all he knew. He used a binary scale to assess his pain: did it hurt or not? But as adults we know better: pain is not a yes-or-no question. Rather, there can be levels, ranking, quantification, and comparisons.

These mental exercises are necessary to keep us going through hard times, no matter what type. Before I got cancer, cancer was a “go-to” negative reference point. I mean, how many times have you thought “I’ve got health problems, but at least it’s not cancer”?

I did that. A benign lump needs to come out? At least it’s not cancer. A mole needs to be removed? At least it’s not cancer. My son has a cyst in his spinal column? At least it’s not cancer.

Then one day it was cancer.

So what could I pacify myself with?

At least it’s not terminal.

At least they can remove the body parts it’s in.

At least I have tools to fight it.

Then there was the big one: at least it’s happening to me and not my child.

I have a few friends with children who have had different types of cancer. These men and women (and their children, of course) are tough and have my utmost respect. I have thought many times, “That is harder. At least that’s not me. I don’t know what I would do.” When my son Tristan was diagnosed with deformities in his neck I thought “at least it’s something physical. At least it’s not something wrong with his brain. At least it’s not something that is fatal.” It’s cold comfort though. It’s still pain. It’s still grief. It is still hard.

I have often said I hate becoming anyone’s negative reference point. “At least I’m not her” someone might think of me. I always thought that meant they pitied me. I didn’t want that. But now I realize that it is okay for people to be glad they haven’t walked in my shoes– in reality, that’s what I want. I don’t want anyone to be where I have been; I’d like to be the lightning rod that keeps others I know safe. But, if it gives comfort to anyone to know that at least for today, their problems are not as big as mine, I think that’s good.

Because actually, at least for today, I’m doing just fine. I had laughs, and warmth, and hugs, and a day without pain—and I know that there are many people out there who can’t say the same.

Today I’m not the last one on line.

April 11th, 2011 §

The months and years go by. Like all of you I mourn the quick passage of time. “Where did the fall/winter/year go?” I hear my friends asking.

The months and years go by. Like all of you I mourn the quick passage of time. “Where did the fall/winter/year go?” I hear my friends asking.

Projects we hoped would be accomplished — tasks we hoped would be done — sit unfinished. Organizing photos, cleaning out a closet or a room, reading that book a friend recommended; many things went undone in the dark and cold months of winter.

Maybe there were emergencies, maybe there were health issues, maybe you just couldn’t get the energy together to accomplish everything you wanted.

Regardless the reason, there can be a bit of disappointment when a season ends.

Growth happens in fits and spurts, not with smooth, sliding grace.

With each phase comes

pain,

discomfort,

unease,

restlessness,

sleeplessness,

yearning.

At the time of my mastectomies the reconstructive surgeon placed tissue expanders in my chest. These were temporary bags of saline that would be slowly filled to stretch out my skin to make room for the silicone implants that would eventually take their place. Each week, like clockwork, I returned to my surgeon’s office. He accessed a port in each expander with a needle and added saline to each side. Each time after a “fill” my chest would feel tight. The skin wasn’t big enough for the volume inside, and it would react to the increased pressure by stretching. Until the skin could replicate there was achiness, tightness, a slight ripping or tearing feeling.

A similar sensation happened to me during my pregnancies. The growth happened fast; I got stretch marks. I had visible proof my skin just couldn’t keep up; the growth was too rapid, too harsh, too vigorous.

I often wonder if mothers and fathers get psychological stretch marks when we are asked to accommodate changes we’re not quite ready for.

What can we do? What options do we have? None. We must “go with the flow” and do the best we can. Our children grow and change whether we like it or not. We do them no favors by trying to protect them, coddle them, and keep them young.

We give them wings to fly when we give them tools to be

confident

and caring

and inquisitive

and trusting

individuals.

I am often moved to tears as I watch my children grow.

I sit in wonder at the succession of infancy, childhood, and adolescence.

I know that as a mother I lack many skills, but I also know that the words I have written in my blogs and essays will one day be a gift to them too.

Not a gift to the children that they are, but instead a gift to the adults that I am raising them to be.

Each August as they go back to school I marvel that another school year has passed and yet another is here.

No matter how you measure time it always goes too fast.

The growth happens too fast.

The growing pains hurt.

The stretch marks might be invisible, but they are surely there.

April 7th, 2011 §

I’m cranky, I’m sad, I’m frustrated.

I don’t want to explain how I feel to family members. I don’t want to have to.

I want to yell, “If you’d had cancer you would understand!” But I know their ignorance is my prize… the prize I get for the fact that some of the people I treasure most haven’t had cancer.

I’ve seen a comaraderie that comes with this disease.

We may have had different types of cancer, different treatments, different prognoses… but… we are tied together.

When I was diagnosed one of the first things I was struck by was how vulnerable I felt. I worried about my family, especially my (then) seven-month old son Tristan who had his own medical problems. “Who will fight for him?” I thought. “No one will love him the way I do. No one will be his advocate the way that I will. I have to do it. I have to be here for him. I have to do what it takes to stay alive.” That became my mantra.

But once introduced, the worry could not be abolished. It could be dampened, minimized, controlled. But it could not be removed.

Two days ago a high school classmate died of brain cancer. Today I got word that a woman I know is in intensive care after complications from leukemia.

I ache for their families, for their children. I can’t explain the nuances of these feelings well. I have been here at the keyboard trying to find the words and repeatedly come up short.

And so, perhaps it is enough to say that I don’t always have the right words to convey what it is I am feeling.

But that doesn’t mean I feel it any less.

April 4th, 2011 §

I have a friend who says that “cancer has been her gift.”

She says that it’s been the best thing that’s ever happened to her.

That perspective doesn’t suit me. Despite being optimistic and determined, I am a realist. I see the ugly warts.

I don’t think it’s the best thing that’s ever happened to me; in fact, I wouldn’t wish it on anyone.

A gift is something you want to share.

Something you want to give to someone else.

Something you say “Next time I need to give a special gift to show someone I care, this is what I want to give.”

Cancer is not that thing.

Language matters.

The words we use to describe illness, death, and emotion are important– we should choose them carefully.

Cancer is not a gift:

It’s what you get.

It’s what I got.

It’s a twist of fate.

A happenstance.

A piece of bad luck.

But once you’ve got it, you have to decide what you’re going to do with it.

You can’t give it away, so you might as well make the best of it.

Fortunately, some good comes with it too.

And one of the best parts is the people you will meet.

Just because you don’t think it’s the best thing,

or a good thing,

doesn’t mean you are a negative person

or a bad person

or any particular kind of person.

In fact, it may mean you are a realistic person.

It may mean you are having a bad day.

Or a good day.

Or just a day.

And you will have those days:

Good

Bad

High

Low

Carefree

Despondent

Manic

Depressed

Terrified

Numb

Grateful

Spiteful

Bewildering

Confused

Overwhelmed

Sleepwalking

Drained

Energized

Proud

Embarrassed

And everything in between.

The days are gifts.

You can celebrate the days.

You should celebrate the days.

But don’t celebrate the disease.

Don’t treat it like a prize.

You are the prize.

You are doing the work.

You get the credit.

March 29th, 2011 §

I get asked a lot about health insurance claims. Having had many different diagnoses, surgeries, and procedures I have became all too familiar with interacting with insurance companies. In the last few years my diagnosis of breast cancer and the almost simultaneous diagnosis of our son Tristan with congenital spine and hand abnormalities has meant a level of paperwork, claims, and appeals I could never have imagined.

Navigating the maze of medical care and health insurance has become second nature to me. I think I’ve resisted writing this piece because initially I thought there wasn’t much to say. Having worked on this piece for weeks now, I realize the opposite is true: there is too much to say. Because each case is different it’s very hard to offer advice on what you, the reader, should do. But I’ve decided that’s the beauty of the blog format: I don’t have to cover all the bases. I don’t have to have all of the answers. I just need to do my best to help. And so today I’m starting to tackle this beast.

I’ve had many requests to write pieces about how to win against health insurance companies and many have suggested I go into this as a profession. I’m not sure about that one but I am definitely willing to share some of the insights I’ve learned throughout the past few years. I do think my upbringing in a medical household (my father was a cardiothoracic surgeon) helped familiarize me with medical terminology and how to correctly present a medical history. In addition to my tips you may be interested to read Wendell Potter’s recent advice in The New York Times: “A Health Insurance Insider Offers Words of Advice.”

Don’t take ‘no’ for an answer

The first piece of advice I have is simple: don’t take no for an answer. The fact your claim was denied is the starting point not the ending point. Insurance companies count on the fact that a large percentage of subscribers will receive a denial and either 1) forget about it, 2) intend to file an appeal but not follow through, or 3) incorrectly file the appeal paperwork (see Potter’s article, above). In any case, if they send you a claim denial and you don’t follow up for any reason, they win.

Always appeal

If you receive a rejection to a claim you feel you are entitled to always appeal. When I receive a claim denial I roll my eyes, roll up my sleeves, and say, “here we go again.” It’s what I expect, but it’s never the last word to me. Now, that is not to say that you always win– but it would take way more than one denial for me to accept that I’m not entitled to have a medical service covered. Persistence and determination are a large part of what it takes to win.

Physical (especially congenital) problems are easier to appeal than those related to developmental delays. I have little/no experience with appeals for diagnoses related solely to delays; while many of my general tips will still apply, more specific ideas will hopefully be available elsewhere online for those types of claims. I do know that when it comes to dealing with insurance companies those types of diagnoses are harder to quantify; this often leads to greater challenges with insurance appeals. In my experience, if the delays can be linked to anatomical problems, orthopedic issues, or diagnoses that can be validated with tests like MRIs or CTs, the case will be easier to justify.

Insurance companies must give you a reason whey they are denying a claim. Most often this reason is that 1) the treatment is experimental or investigational, 2) the treatment is not medically necessary, or 3) the treatment is not the standard of care.

In our case, initial denials have most often been because it wasn’t considered medically necessary.

Show the progression of the situation and how options have been exhausted

I always try to base appeals on the phrases “medical necessity” and “medically necessary.” When you document a surgery or service that you or your family member needs:

Be clear how it is necessary to daily functioning.

Describe what will happen if what you are asking for doesn’t happen.

Be sure to tell what you have tried already, and what has failed.

Show how your diagnosis and treatment history has brought you to this place–how there is no other reasonable option to what you are asking for (or how the alternative is not preferable).

Be complete but don’t ramble.

Be sure to include diagnosis codes and treatment codes (your medical professional will provide these).

Doctors’ offices don’t always have the final say

I should point out that a doctor’s office may tell you that you will have to pay out-of-pocket. They may tell you that they have tried to get your service covered, it was denied and therefore this is the last word. It’s not. For example, my neurologist’s office tried to get my Botox injections covered. Their office appealed the first rejection. They were again denied. They told me that there was “nothing else they could do”; I would have to pay.

Undeterred, I asked for copies of my medical records. I called my insurance company and asked what I needed to do. Despite what the doctor’s office told me, I learned that patients often have a separate appeals process available to them. While physicians’ offices can often get services covered and can be very helpful in knowing what’s been a successful method of appeal in the past, they are not the only way to get services approved. In a case like this there is actually a financial disincentive for them to have insurance cover it; therefore, they may not be as aggressive as you will. What does that mean? If I had paid out of pocket they would have received almost three times the amount of money that they receive when compensated by my insurance company directly.

When the office tried to get the injections covered, the insurance company denied the request on the basis that this was an experimental treatment– not FDA-approved for this use. I provided medical history sheets from my medical file. I documented every drug I had take until that point to try to prevent migraines and the dates I took them. I explained the medical condition/situation that resulted when I had migraines. I told them how the neurologist felt the Botox might help me. I included the original letter he had written to the insurance company. I explained that if they didn’t cover this treatment a more expensive, more medically damaging situation would result– this would mean more claims and more expense for the company. In the case of the migraines I documented how much my “rescue medications” were costing them per month and how a reduction in those would easily pay for the Botox I was asking for. I showed through my history with the numerous failed attempts with other drugs that the situation had not improved and in fact the side effects from those drugs had been debilitating. I also showed the literature about preliminary success in clinical trials with Botox and my neurologist’s observations about its efficacy in others and the potential efficacy in my case. I explained I had no other choice, and while it might be not-yet FDA approved, Botox was actually on the verge of receiving such approval (I was proved right when it did receive approval for this purpose less than one year after my request).

Include all relevant information and send appeal within the required time period

This letter of appeal doesn’t need to be 3 pages long. In fact, even in my most complicated appeals I didn’t write more than a page or two at most (plus the inclusion of the supporting documents). Be sure to appeal/respond within the time frame they dictate. In the letter be sure to include:

your contact information, subscriber number, and the doctor/hospital/treatment facility information

the case reference number that they provide

all relevant diagnosis and procedure codes

Ask doctors and staff for assistance, documents

Do not be afraid to ask your doctor and his/her staff for help: what tactics have they found useful? If there are multiple codes that apply which ones are the best to use? Do they have any sample letters for appealing? What has their experience been with your particular health insurance company?

Use the rejection letter as the foundation for your appeal

Take the rejection letter you received and read it carefully. Don’t just react with “it says no” and throw it away. It is vital; in it, the company must tell you why they are rejecting your claim (usually one of those three reasons I mentioned at the outset). This is the key to your appeal. You must address this issue. They’re telling you the basis, you need to fight based on that. Be thorough but don’t get off track.

Another good example of persistence in appeals came with a corrective band we used for Tristan’s quite-misshapen head (diagnoses of plagiocephaly and brachiocephaly). The facility we used for the DOC band told us that insurance claims were most often denied for this service. Indeed, the first claim was denied; they said the “helmet” to correct his misshapen head was for cosmetic reasons only. I appealed. I explained that because of his neck abnormalities the head deformity was an inevitable result of having his head fixed in one place. Because he was unable to move his head properly he had this inevitable result of a physical abnormality. I ended up having two helmets approved for coverage. Had I accepted the facility’s statement that “insurance companies usually don’t pay for this” or my first rejection letter from the company, we would have had to pay in full for both helmets. I should point out that I’ve seen success getting this particular service covered even when the plagiocephaly was not due to a unique condition like Tristan’s when the subscriber persisted with the appeal process.

You can appeal more than just a denied claim

– A facility that isn’t usually in-network may actually be considered in-network for some diagnoses. For example, Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital in New York City is a hospital that specializes in treatment of cancer. Though it isn’t normally included in coverage by some health plans, insurance companies will often allow oncology treatments there under the Centers of Excellence program. Through this policy, hospitals that specialize in certain conditions are treated as participating centers (in-network). So, if you wish to have medical care at a facility that specializes in a certain medical condition be sure to check whether they are included in this special program.

-Prescription drug plans can be adapted. This is a big one. What do I mean by this? Just because your prescription drug plan says it will only cover a certain number of pills doesnt mean that’s the last word. My prescription drug plan said only 9 pills of my expensive migraine medication would be covered each month. The problem? I frequently needed more than that number. I decided to investigate. I called my insurance company and the administrators of the prescription plan and asked how I could get that number increased because it was medically necessary for me to have more than that number. They said my doctor could call and make a request. He called and they agreed to cover 18 pills. I received a temporary increase to 18 pills a month for one year, renewable each year by going through the same process. That saves me up to $2880 a year.

-Additionally, numbers of physical therapy/occupational therapy visits can be appealed. Our plan covers 30 PT visits for Tristan per year. He needs significantly more than that number. When the 30 are up, I write and document the medical necessity for him to receive more based on his anatomical defects. I state the skills he is getting with the visits and how they are necessary for his functioning. The physical therapist sometimes needs to include a letter and our pediatrician needs to write a prescription for the services.

Be organized. Take notes. Document everything

No matter what drug, service, surgery, or treatment you are appealing, you must be organized, take notes, and document everything. The key to my system is my medical binder. Have one for each family member. To see how to organize this essential tool, read my blogpost here.

Keep copies of your lab results, operative notes, and copies of all communication to/from your insurance company.

Be sure to have a fully documented medical history.

Save letters that were successful; if you need to repeat an appeal annually (like my migraine drugs and Tristan’s PT visits) then you will have a document that just needs minor tweaking.

Take notes on conversations (including dates and full name of the person you spoke with) at the company or doctor’s office. I learned that tip from my grandfather, a court stenographer for over 50 years: always keep track of the date, time, and name of the person you talked with. It may not be enough to prove your case, but if you can say “I spoke with (first and last name) on (date)” it lends credence to the fact that conversation took place.

Obviously, this post is not a comprehensive list of all types of conditions and how to win appeals for them. I know there are many readers who have had/will have experiences different from my own. I cannot tell you what will work for you; I can only tell you what has worked for me. I hope that by doing so and sharing some of these anecdotes you will learn something that you can apply in your own case. I realized while writing this piece over the past few weeks that there is so much to say about it. I’d like to consider this post an introduction to the topic; I will definitely revisit it again in the future.

March 18th, 2011 §

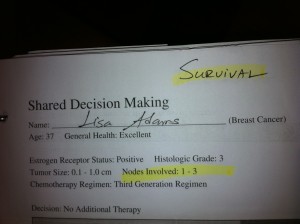

What if I hadn’t gone to the gynecologist on time for my 6 month post-partum visit?

What if, during the breast exam, when my left breast felt “different” (no lump, no real reason, just “different”) my doctor had dismissed it as post-nursing irregularity and told me to come back in 6 months for another exam?

What if, when I called to schedule the mammogram (only 18 months after a clear one) and they said it would be a few months for an appointment I had said, “Okay”?

What if I hadn’t called my doctor to tell her that’s how long it would take and ask if that was acceptable?

What if she’d said “yes”?

What if I hadn’t opted for a double mastectomy?

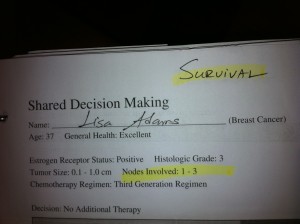

What if I hadn’t gone for a second opinion on chemotherapy? What if I hadn’t gotten a second pathologist to review my slides?

What if that didn’t happen and I didn’t find out with that second look that I actually had invasive ductal carcinoma in one breast, in my lymph node, and dysplastic cells in the other breast?

What if I had decided not to do those things? Where would I be now?

What if I hadn’t been assertive, perceptive, inquisitive, impatient, and willing to do what it took to get answers?

I probably wouldn’t be alive. Or if I were, I’d be spending my time treating an advanced cancer.

Not blowing bubbles with Tristan today,

Not praising Colin for his schoolwork,

Not planning Paige’s sleepover for tomorrow.

I wouldn’t be able to enjoy the things I enjoyed today.

But I am here.

I was able to be with my family.

I was able to help others.

I am able to look to the future with hope.

And for that, I am happy.

March 16th, 2011 §

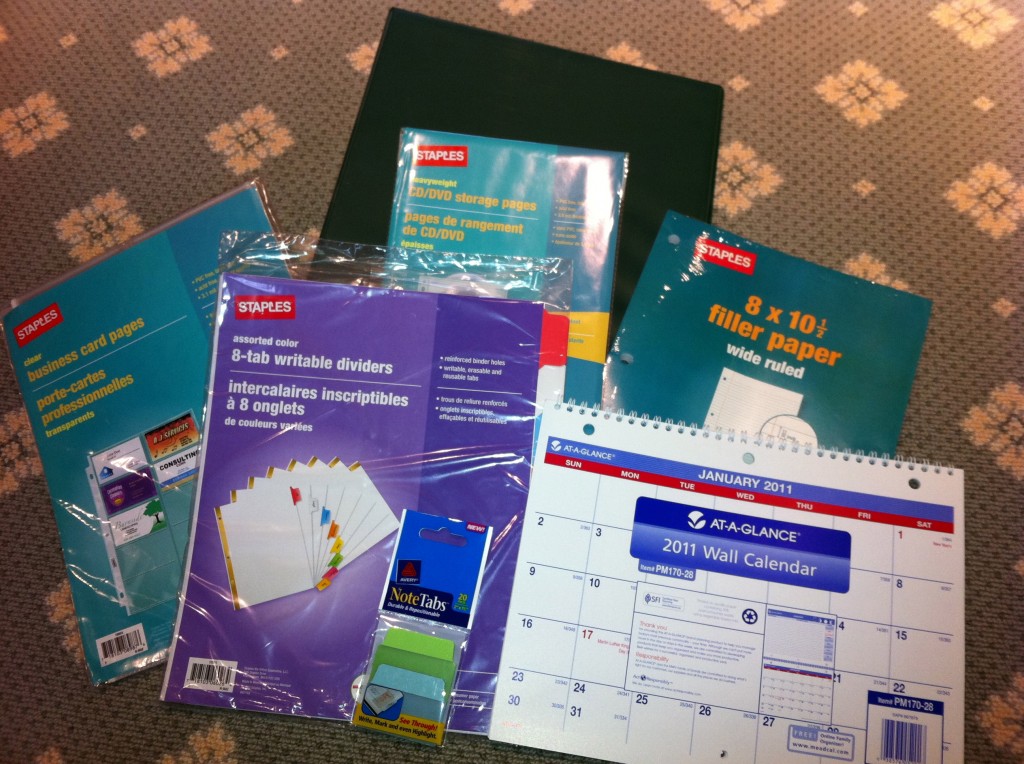

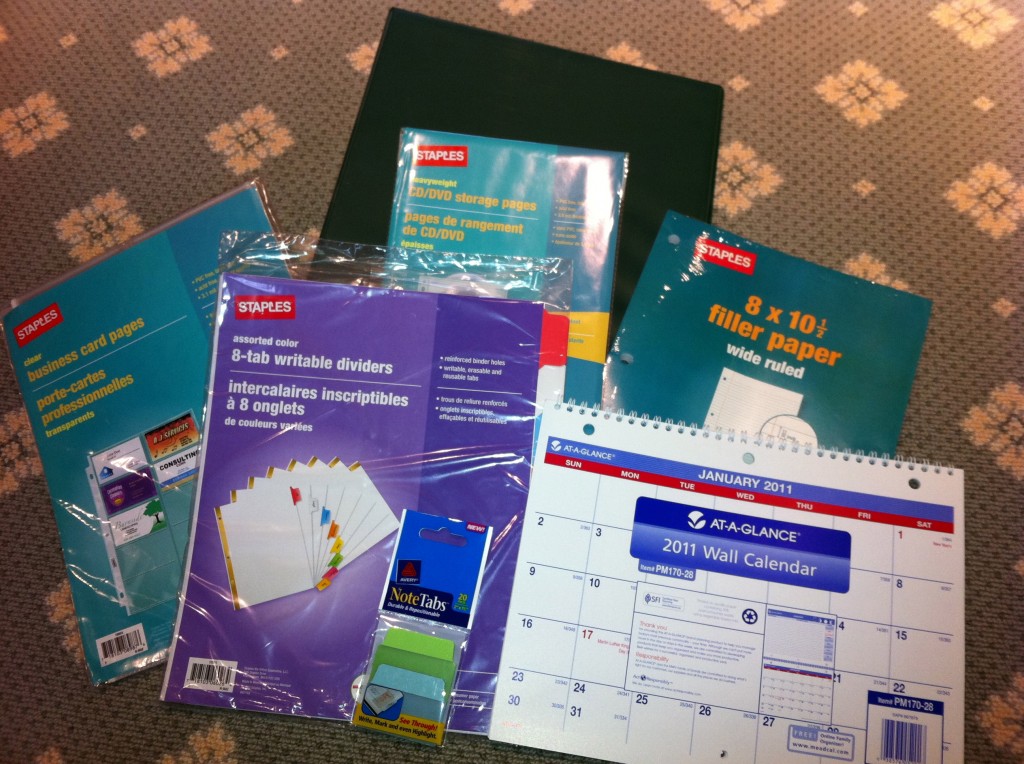

Perhaps the most common question I get asked by email is, “Someone I know has been diagnosed with cancer. What can I do?” Today I offer one suggestion. I believe this would make a wonderful gift for someone who has just been diagnosed and is a necessity if you are the patient.

Perhaps the most common question I get asked by email is, “Someone I know has been diagnosed with cancer. What can I do?” Today I offer one suggestion. I believe this would make a wonderful gift for someone who has just been diagnosed and is a necessity if you are the patient.

Being organized is one of the best ways to help yourself once you’ve been diagnosed. When you first hear the words, “You have cancer” your head starts to swim. Everything gets foggy, you have to keep convincing yourself it’s true.

But almost immediately decisions need to be made — decisions about doctors, treatments, and surgeries. Often these choices must be made under time constraints. You may be seeing many different doctors for consultations. Medical oncologists, surgical oncologists, radiation oncologists, recontructive surgeons, internists— there are many different voices that you may hear, and they may be conflicting. It’s hard to keep it all straight in the midst of the emotional news. Not only are you likely to be scared, but also you are suddenly thrust into a world with a whole new vocabulary. By the time you are done with it, you will feel you have mastered a second language.

You can help your care and treatment by being organized. Especially if you are juggling different specialists and different medical facilities, you must remember that the common factor in all of this is you. It’s your health. It’s your life. I believe it’s important to travel with a binder of information about your medical history and treatment, as well as notes and questions.

This binder will mean that all of your information about your cancer will be in one place. This will be your resource guide. I cannot tell you how many times physicians have asked about my binder and said when I was able to produce test results, pathology reports, or other information they needed, “I wish every patient had one of those.”

I suggest the following:

A heavy 3-ring binder

I think a 1.5″ binder is a good size to start. This size will allow you to easily access reports and pages and have room for the calendar. It will look big at first but you won’t believe how quickly you will fill it up.

Colored tab dividers

I like these to be erasable. I think 8 is the minimum number you will need. If you have a lot of specialists you will need more. The categories you think you will need at the outset may change. It’s easy to erase and reorganize them. Put the categories you will be accessing the most in the front so you aren’t always having to flip to the back. Once the binder is full it will make a difference.

Some starting categories:

- schedules (dates of appointments you have had, when the next ones are due, and how often you need certain tests done)

- test results/pathology (it’s very important to keep copies of MRI, CT, and pathology reports so that you correctly tell other doctors what your diagnosis is. For example, new patients often confuse “grade” with “stage” of cancer.)

- insurance (keep copies of all correspondence, denial of claims, appeal letters, explanations of benefits)

- articles and research (handouts, post-surgical information. Ask if there are any websites your doctor does approve of. My own oncologist said, “Do not read anything about cancer on the internet unless it comes from a source I’ve told you is okay. There’s a lot of misinformation out there.”) Keep your post-surgical instructions, any info given to you about aftercare.

- radiation/chemo (keep records of exactly what you had done, number of sessions, dates, drug names, etc. I also asked how my dose was calculated so I knew exactly how much of each drug I received in total)

- medications (drug names, dates you took them, dosage, side effects). I also keep a list of all of my current medications as a “note” in my iPhone. That way I can just copy it down and won’t forget anything on the list. You should always include any vitamins or supplements you take.

- medical history (write out your own medical history and keep it handy so that when you fill out forms asking for the information you won’t forget anything. As part of it, include any relatives that had cancer. Write out what type it was, how old they were at death, and their cause of death. Also in this section include genetic test results, if relevant)

Loose leaf paper

Perfect for note-taking at appointments, jotting down questions you have for each doctor. You can file them in the approporiate category so when you arrive at a doctor your questions are all in one place.

Business card pages

These are one of my best ideas. At every doctor’s office, ask for a business card. Keep a card from every doctor you visit even if you ultimately decide not to return to them. If you have had any consultation or bloodwork there, you should have a card. That way, you will always have contact information when filling out forms at each doctor’s office. For hospitals, get cards from the radiology department and medical records department so if you need to contact them you will have it. Also, you want contact information for all pathology departments that have seen slides from any biopsy you have had. You may need to contact them to have your slides sent out for a second opinion.

This is also a good place to keep your appointment reminder cards.

CD holders

At CT, MRI or other imaging tests, ask them to burn a CD for your records. Hospitals are used to making copies for patients these days and often don’t charge for it. Keep one copy for yourself of each test that you do not give away. If you need a copy to bring to a physician, get an extra made, don’t give yours up. If you need to get it from medical records from the hospital, do that. You want to know you always have a copy of these images.

Keep a copy of most recent bloodwork (especially during chemo), operative notes from your surgeries (you usually have to ask for these), pathology reports, and radiology reports of interpretations of any test (MRI, CT, mammogram, etc.) you may have had. Pathology reports are vital.

Calendar

I suggest a 3-hole calendar to keep in your binder. This will serve not only to keep all of your appointments in one place but also allow you to put reminders of when you need to have follow-up visits. Sometimes doctor’s offices do not have their schedules set 3, 6, or 12 months in advance. You can put a reminder notice to yourself in the appropriate month to call ahead to check/schedule the appointment.

Similarly you can document when you had certain tests (mammograms, bone density, bloodwork) so you will have the date available. I usually keep a piece of lined paper in the “scheduling” section of my binder that lists by month and year every test/appointment that is due and also every test I’ve had and when I had it.

Sticky note tabs

These can be used to easily identify important papers that you will refer to often, including diagnosis and pathology. These stick on the side of the page and can be removed easily. As your binder fills up, they can be very helpful to identify your most recent bloodwork, for example.

Plastic folder sleeves

These are clear plastic sleeves that you access from the top. They can be useful for storing prescriptions or small notes that your doctor may give you. The sleeves make them easy to see/find and you won’t lose the small slips of paper. Also a good place to store any lab orders that might be given to you ahead of time.

The above suggestions are a good working start to being organized during your cancer treatment. If you want to do something for a friend who is newly diagnosed, go out and buy the supplies, organize the binder and give it to your friend. He or she will most likely appreciate being given a ready-made tool to use in the difficult days ahead.

I also believe a modified version is equally useful for diagnoses other than cancer. When our youngest son was born with defects in his spine and hands it took many specialists and lots of tests to get a correct diagnosis. Having all of his tests and papers in a binder like this was instrumental in keeping his care coordinated. In fact, at his first surgery at The Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania they gave us a binder to assist in this process. I know some hospitals do this for newly diagnosed patients already. Maybe my tips will help you or a friend know how to better use the one you already have. You may not need all of these elements depending on the complexity of your case, but I hope you will find some of these suggestions useful.

March 9th, 2011 §

Just because you know someone who died from cancer doesn’t mean I will.

Just because you know someone who:

felt sick,

felt great,

felt tired,

felt strong,

looked great,

looked awful,

lost her hair,

kept her hair,

ate healthy,

ate crap,

took vitamins,

ignored medical advice,

got acupuncture,

believed in holistic medicine,

ate no soy,

ate no sugar,

never laughed,

never cried,

had surgery,

had radiation,

received chemotherapy,

got silicone implants,

got saline implants,

had a great attitude,

had a terrible attitude…

Just because you know someone who did

one of these things,

many of these things,

some of these things…

doesn’t mean it will work for me.

It doesn’t mean it will kill me.

It doesn’t mean it will make me live.

Just because it worked for someone else doesn’t mean it will work for me.

It doesn’t mean it won’t.

Or can’t.

It might.

It might not.

Just because you know someone who died from cancer doesn’t mean I will.

February 23rd, 2011 §

When you (or a family member) are diagnosed with cancer people say a lot of insensitive things. It may be intentional or it may be just because they are caught off-guard and don’t know what to say to you. They ask bizarre questions, and often do bizarre things.

Sometimes you laugh.

Sometimes you just shake your head.

Sometimes you get angry.

But rarely do you forget.

So, today’s question is: what are the weirdest/craziest/most bizarre/most insensitive things people said to you/did to you while you or a family member or friend were going through treatment for cancer? Or died from it?

I have a few notable ones, but I’ll start with just one to kick things off. Someone asked me, “Is cancer what’s going to kill you? I mean, could you die from something else?”

February 22nd, 2011 §

I’m not really sure when I started #mondaypleads… I think it was about a year ago. On Twitter (@adamslisa), I got in the habit of nagging folks to go to doctors’ appointments. It started with mammograms. But soon I was sending out tweets gently nagging folks to take care of themselves and their families with a list of things I thought they should be doing. I had noticed that people were good at taking care of their children and their pets, but when it came to themselves– not so much.

At that time I had also become involved with a startup meme called #fridayreads. Now, I guess at this point I should assume that some of you are already wondering why I am writing with the number sign and why there were no spaces between those words. And what the heck is a meme? (that’s pronounced “meem” not “meemee” by the way)

For those who aren’t familiar with Twitter, here’s a brief explanation of hashtags. For a wonderful and humorous lengthier explanation of hashtags, please read Susan Orlean’s piece in her The New Yorker blog entitled “Hash”. The hashtag is that number sign (#), and one of the uses of hashtags is as a search tool. You can include a hashtagged term in your tweet (a tweet is a message of 140 characters) so that others can easily search for it. So you could hashtag #cancer or #snowpocalypse or #Egypt and then anyone with an interest in those topics could search for them and read tweets related to those things.

Now, one of the cool things about Twitter is that you can create a term; that is, you can make up a hashtag that will represent your idea. That’s a meme: a concept that spreads througout the internet. So… when my friend Bethanne Patrick (@thebookmaven) of The Book Studio wanted to start a meme to celeberate reading and have people share the book that they were reading with the Twitterverse each week, she started #fridayreads. Now with over 6,000 participants, the #Fridayreads team (through Twitter, an iPhone app and Facebook page) shares one of the things we love most: books.

Once I was involved with #fridayreads I wanted to create a meme to capture the nagging that I was doing and decided Monday was the day to do it. To try to be catchy, I created one to rhyme with #fridayreads: #mondaypleads. (By the way, I also created the #dailynag, a daily reminder for people to take their medications and vitamins. If you follow me on Twitter, you get a reminder each day.)

#mondaypleads has become what I consider to be an enormous success. I have received numerous messages from my followers that they appreciate the nagging, the gentle nudge it often takes to just do something you already know you should be doing. They tell me when they made the appointments, they tell me when they are going, they tell me how they went. It makes me feel good to know that people are listening, and doing.

I’ve even had a few cases where some of my 2000 followers didn’t know they should be going for some of these routine visits. One man read a tweet I made during #mondaypleads about going to the dermatologist for a skin check. He sent me an email: “I am in my 60s and have been a sailor for much of my life. Was there something I am supposed to be doing to monitor my skin?” I told him he should go to the dermatologist for a skin check to look for any suspicious moles and document the ones he has. He made the appointment. He went… and found he had two moles that were on their way to becoming malignant. They were removed before things got more serious. That’s exactly what you want: find things out while you can still deal with them relatively easily.

So… now you know the history. Now, on to the list.

Here’s what I do at home to organize my list: I have a binder of my medical records and reports with a piece of paper in it. The paper lists all of the doctors and specialists and tests I have had/need. I have the date and place that it was last performed and when I need a follow-up (6 months, a year, every 5 years, etc.) Every time I have a test, procedure, follow-up or appointment, I note it in this section. That way I never have to wonder “When was my last MRI and when am I due for another?” or “When did that doctor say I was supposed to come back?” If you have lots of tests, it’s a great way to keep track of what you had and where. If you only have a few appointments it’s easy to keep track of them if you keep them in a file or an iPhone note.

By the way, one of the best things you can do if you take a lot of daily medications is to put that list in an iPhone note (or similar memo). I have a note called daily medications that I update each time my dosage or cocktail changes. That way, when you go to a new doctor or are asked to update your medication list it’s easy to recreate– you just open this note on your phone and copy it. This has been an easy and useful tool for me, especially during the months when certain medications were changing. It’s also handy that a family member can easily access this information in case of an accident or emergency.

Here is a basic list of what I think people should be doing for themselves. Depending on your medical conditions you will need more than this. I’m not a doctor, these are just some suggestions of things I think people should be doing (at a minimum) to keep up to date.

— (For women) mammograms, PAP smears, and annual gynecological exams. Discuss the frequency of these with your doctors, based on your age and medical/family history.

—Dental visits every 6 months.

—Annual physical/internist visit, including vaccine boosters. Ask about tetanus and pertussis boosters; I needed those recently. If you are over the age of 50 ask your doctor about the shingles vacccine. May need to monitor kidney and liver function, blood pressure, and cholesterol. Men should have PSA screenings once they reach a certain age. Discuss the timing with your doctor. Here is a recent article about the guidelines for adult immunizations. There is a PDF for viewing the list in chart form by age.

—Depending on your age you may need a bone density test, especially if you are a post-menopausal woman, went through menopause at an early age, or have a history of breast cancer. Certain drugs and treatments may affect your bone strength. Talk to your oncologist or internist.

—Annual skin check at the dermatologist to document and monitor moles

—Annual eye exam

—Depending on your particular medical conditions, endocrinology visits to monitor bloodwork including thyroid and blood sugar issues, especially if you have weight issues.

—Colonoscopy. Check with your doctor when to start doing these; it will vary based on family history. No one wants to talk about them but they really are not bad, folks. Find any problems early and your outcome will be better. I’ve had two already and so I’m not telling you to do something I haven’t done.

—Make sure your will and end of life directive are up to date. No one wants to think about dying but knowing your wishes will be carried out can be a relief. Make sure someone knows where these papers are and a copy is accessible in case of emergency. Also, adequate life insurance is a must… and best arranged while you are still young and healthy.

— Finally, here is information from Yale on becoming an organ donor. You could save a life by becoming one. Please donate blood, platelets, and get tested with Bethematch.com to be part of the bone marrow registry.

Again, these are the basics. It takes a lot to keep on top of your health. There is no better investment you can make than in yourself. I hope this helps!

p.s. If you have a chronic medical condition have been recently diagnosed, or are a caregiver, my blogpost about organizing your medical records, test, and papers may be helpful. Go here to read “The Must-have Binder: my key to being an organized patient or caregiver.”

February 7th, 2011 §

I’ve written previously about my decision to have my ovaries removed two years ago in order to (hopefully) decrease the likelihood that my breast cancer will recur (“The Impetus of Fear”). Though I tested negative for the BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 genes, my hormone receptor positive cancer feeds off of the hormones that my ovaries produced. To significantly reduce the amount of those hormones circulating in my body (as a pre-menopausal woman of 38) I decided to have a salpingo-oophorectomy (surgical removal of my Fallopian tubes and ovaries). I recovered from the surgery itself within two weeks; the effects of plummeting into menopause overnight have been longer-lasting and in some cases, quite devastating.

As I do with almost any issue in my life, I have repeatedly talked to my mother, Dr. Rita Bonchek, about the ramifications of my decision. This angst has led to many talks about the difference between regret and guilt. As a psychologist specializing in issues of grief, loss, death, and dying for twenty years, she always has a keen ability to separate out what appear to be muddled feelings. She often has ways of explaining complicated topics in easy-to-understand terms and using real-life examples to illustrate her points. She and I have collaborated here to present some thoughts on these two emotions. The ideas on the differences between guilt and regret are hers; I have pushed her to explain things as fully as possible and helped with some of the re-writing.

We hope that they will help you to think more clearly about actions in your life and the emotions you have about them. We look forward to hearing your comments and any follow-up questions you have. Because my mom is not on Twitter, if you have any questions for her, it’s best to put them in a comment below; I’ll post her answers for everyone to read, too. This is meant as an introduction to these two emotions, not a comprehensive analysis of them.

………………………………….

People use the word “guilt” more often than is appropriate. Improperly using the word “guilt” can result in unnecessary emotional distress and harsh self-criticism. The word “guilt” refers to something you did, something which you feel you shouldn’t have done because it was morally or legally wrong. But what if the experience you feel guilty about was not something you caused or had control over? Then you would feel regret, not guilt.

Here is an actual situation: Ann was referred by her family doctor for grief counseling. She was unable to cope with her persistent feelings of guilt related to her husband’s death several months prior. Bob was diagnosed with a terminal illness and he was bed-ridden. He needed constant care and attention which was mainly provided for by his wife. Bob was hospitalized for three weeks prior to his death. Ann was with him throughout that time as well.

On the day of Bob’s death, his wife left the hospital room to use the bathroom. When she returned to the room, the nurse told her that Bob had died in her absence. Ann was overcome with feelings of what she termed “guilt” and punished herself for not having been with Bob at the time of his death. For months she could not function and was preoccupied with thinking how terrible she was in being absent when her husband died. She mentally punished herself for breaking the vow she had made to herself to be with him when he died. Instead of focusing on the 99% of the time she had cared for him while he was ill, she focused on the last minutes he lived.

Why shouldn’t Ann feel guilty? Because she did not do anything that caused her husband’s death; she was not there. If Ann had asked the nurse whether it was “safe” for her to leave for a few minutes and the nurse had cautioned her that Bob could die at any time, and then Ann chose to leave, then she could justly experience guilt because she ignored information indicating he could die during the time she was away. In this alternate scenario, Ann had the personal responsibility for making the decision to go, she had control of making the decision that resulted in her absence, and could therefore justly experience feelings of guilt. As a counselor, if someone is justifiably guilty for an action, I would advise them to make a confession, offer an apology, take responsbility, and — if possible– make reparations.

By disproportionately magnifying these few minutes to overshadow all of the months of care Ann had given Bob, the result was that she could not forgive herself. After discussing the difference between regret and guilt, Ann came to see that there was, in fact, nothing to forgive. She understood that she was only responsible for her own actions; Bob didn’t die because she left the room. By reframing the circumstances of Bob’s death, Ann was better able to properly grieve her loss and move on afterwards.

Though Ann did not experience guilt, she did have regret, a universal experience. Regret refers to circumstances beyond one’s personal control. An unidentified author defined regret as “distress over a desire unfulfilled.” Regrets can pertain to decisions made concerning: education (not getting a degree), career (working at a job that offered good income but no personal satisfaction), marriage (married too young), raising children (being too permissive), medical decisions (sterilization), etc. These and other decisions can be considered mistakes.

As an emotional response to a distressing experience, the sound of the word “guilt” is harsher and more of a self-reproach than the word “regret.” If you say, “I feel so guilty” you should make sure that the deed and circumstances surrounding it actually warrant your feeling of guilt rather than regret.

Dr. Rita Bonchek has a Ph.D. in educational psychology. She spent twenty years in private practice.

Dr. Rita Bonchek has a Ph.D. in educational psychology. She spent twenty years in private practice.

February 2nd, 2011 §

I remember distinctly sitting in movie theaters when I was pregnant. At various points throughout the film I’d tune out the words and images and get lost in my belly, feeling each of my children squirm and wriggle and stretch. “What if this is it?” I’d think to myself. “What if I go into labor right here, right now?” And then I’d think to myself, “In just a week or two I’ll be a mother, mother to a person whose body is inside mine but whose face I have not seen, whose voice I do not know, whose skin I have not touched. I’ll be mother to this person for his or her entire life, my life will be shaped by his, and his by mine.” And those thoughts seemed incomrehensible to me at the time. Too large, too vast.

I remember distinctly sitting in movie theaters when I was pregnant. At various points throughout the film I’d tune out the words and images and get lost in my belly, feeling each of my children squirm and wriggle and stretch. “What if this is it?” I’d think to myself. “What if I go into labor right here, right now?” And then I’d think to myself, “In just a week or two I’ll be a mother, mother to a person whose body is inside mine but whose face I have not seen, whose voice I do not know, whose skin I have not touched. I’ll be mother to this person for his or her entire life, my life will be shaped by his, and his by mine.” And those thoughts seemed incomrehensible to me at the time. Too large, too vast.

Then four years ago my little mental interludes changed form. “I have cancer,” became the thought that was too big to wrap my brain around. “Right now, while I am sitting here the cells are there. There is cancer in me. Right now,” I thought to myself. Eventually, after my double mastectomy, during my reconstruction, I could sit, arms crossed across my chest and feel the tissue expanders in me. And even now, I need only take a sharp, deep breath to feel the implants in there, reminding me of what has come to be.

Sometimes, when there is a lull in a movie, I still “check out.” Just for a few moments.

As if when I am sitting there,

in the theater,

away from everyday distractions,

lost in someone else’s life,

only then can I think about the larger things that haunt me.

The other night I found myself momentarily thinking about my body, and its cells. “Are there any cancer cells left?” I thought. “What if there are some still there, right now, dividing, multiplying, gathering momentum.”

I sat and wondered if they’re gone. If they’re not. I wonder what the plot will be, how it will end. My favorite movie endings are the ones where you get to see what happened to the characters– how things ended for them, what the final chapter was– an epilogue. I realize I can’t have that knowledge about myself. And I’m not really sure I’d even want to. I guess everyone likes a happy ending. That’s the only kind I really wish I could know about myself.

January 27th, 2011 §

I love this piece in the New York Times about the myth that a fighting spirit and good attitude make all the difference in how (and if) you recover from a life-threatening condition. I wrote a piece in 2009 about this and am reposting here since the topic has received attention this week.

…………………………………

“Having a good attitude makes all the difference.”

People say that to me all the time. I am sure every person who’s had cancer hears that. I think what people are saying is that there is something you can control in all of this mess. There is so much you can’t control, that you have no choice in. People say how you deal with it, how you choose to behave once these things are thrown your way, is up to you.

Here’s what I think:

I think what matters is good health insurance. I think what matters are friends and social support to get you through. I think what matters are children, or pets, or others who nurture your soul and remind you why you are going through all of this: there are others who care about and depend on you.

I think good medicines matter. I think caring and capable oncologists matter. I think talented surgeons matter. I think getting good advice matters.

Why am I resistant to the idea that attitude matters? Not because I don’t believe it. I reject this idea because it places the burden of healing on the individual patient. It places the weight of getting better in his/her hands. I think cancer patients have enough to deal with. We have enough to feel guilty about and responsible for. I think tossing our collective attitude into the mix is a lot of pressure. All eyes are on us anyway.

Now we have to watch how we treat the thing which is killing us.

Having a good attitude says:

the power is in you to survive.

The power is in you to heal.

The power is in you to do well.

But looking at the converse is troubling. The implication is that if you suffer, if you relapse, if you die– it is your fault.

If you had only had the right attitude,

you could have been better at keeping it away.

You could have been stronger.

You could have beaten it.

That may be flawed logic in the philosophical sense but I think it’s worth exploring. Even if that logic can’t be reversed so easily, I think the implication is there: you should have the right attitude because it makes a difference. Difference in what? Difference in your outcome. If it didn’t, then they would not say it.

Or would they?

There is an impetus to control, as I’ve talked about frequently in my writing. You just feel like you need to do something. I think that’s what people are grasping on to with their advice. They know you can’t do much, so they tell you to control the one thing you can: your mindset about what is happening to you.

Sometimes I just don’t want to have a good attitude.

I don’t necessarily think it makes a difference.

I don’t want to think positive thoughts all day

and see the good in what is happening to me.

I think that can be healthy too.

January 27th, 2011 §

This post was written at a time when I was feeling down, fatigued, weary. I started thinking of all of the things that I was looking forward to when I felt better, things I hoped for the future, things I was thankful for along the way. These would be my payments; these were things that I accepted for my struggle.

……………………………………

A currency of thanks,

a commodity of gratitude,

a medium of memories.

Hugs

smiles

laughs

tickles

sunny days

warm laundry

long baths

newly-mown grass

freshly-baked cookies

hot coffee

baby snuggles

happy endings

clean floors

baby shampoo

good blood counts

clear scans

easy blood draws

short waiting room waits

no side effects

no hidden costs

generous co-pays

quiet offices

pain-free mornings

guiltless decisions

days without regrets

unconditional love

fading scars

new friends

caring surgeons

information

honesty

openness

truth

validation

appreciation

understanding

sympathy

hope

research

progress

empty parking spaces.

someday, my hope:

no more cancer.

January 21st, 2011 §

Beautiful.

It’s not a word I have used to describe my body. Ever.

Even when I was young and lithe and strong I didn’t think of myself that way.

After three pregnancies that word was certainly gone from my vocabulary.

I loved and appreciated my body for what it had done, what it could do. However, that feeling was more a result of recognizing its practicality more than its aesthetic appeal.

When I was diagnosed with cancer everything changed.

One aspect: body parts became liabilities.

It doesn’t matter, people said, you are the same person inside.

Was I? Am I?

Ripples replaced smooth expanses of skin.

Rosy scars replaced creamy white flesh.

I didn’t mind them then– I don’t mind them now.

Or do I?

When the glass is half full it is still also half empty.

I can see both views by shifting focus.

I’d rather be scarred than dead…

…but I’d rather have been healthy than ill.

I miss the hormones. My life is not the same since the removal of my ovaries shut down almost all of my estrogen production. One of my doctors told me the change would not be radical. She was wrong. There isn’t a day that goes by that this decision doesn’t affect my life.

When we’re in the thick of it we are afraid. We think fear is bad, but in fact the fear is useful: fear causes us to be brave.

Fear allows us to do things we never thought we would have the strength to do. Chemo was my greatest fear; I literally made myself ill with fear about receiving chemotherapy. I wanted any excuse not to do it. Saying no to chemotherapy would have been the wrong decision for me to make based on my particular risks. My fears of metastasis, dying young, and leaving my children was greater. I needed to do everything I could: that was my mindset. Whatever it takes.

I have reminders every day that I am not who I used to be.

And so, when I think of the words you are still the same person I realize it’s not true.

I’m not the same person… and I think that’s okay.

In fact, I’m not sure it could be any other way.

I ordered the book The Scar Project in October and finally received it two weeks ago. Photographer David Jay has been photographing breast cancer patients who were diagnosed between the ages of 18 and 35. The images are stark, real, true. The book has statements from the subjects, a bit about their cancer experience in their own words. I realized when I looked at them how beautiful the women were. That’s the word that instantly came to mind: beautiful.

With scars, without breasts, without hair… whatever each picture showed I found myself thinking how powerful those images and words were. And then I realized something: I am one of them. If they are beautiful so am I. It isn’t just their bodies, it’s their strength. Maybe my definition of beauty has changed; I just see it as meaning more than it used to.

Now that I am older I see that resilience is beauty. Scars can be inspiring. Scars are the marks we have to show that we have lived, endured, survived. I need to be willing to say that if those women are beautiful, so am I. Why I still have a hard time saying that, I don’t know.

Of course I am sure that is what David Jay wants to happen with his project; he wants to show that the reality of life with cancer is one that can be empowering. I do draw strength from my past, but the mixed emotions inside continue to wrestle with one another. David Jay has succeeded: he has shown strength in beauty and beauty in strength.

I need to do the same.

January 19th, 2011 §

April 1, 2009

How can you be a good friend to someone with cancer? Doing the same things you do for any friend: show you care, express interest in her life, be sympathetic, and offer to help when she will let you. The best thing you can do is to be a good listener.

Being a good listener seems obvious, but it’s harder to do than it sounds. First, you need to remember that if you haven’t had cancer, you aren’t going to really understand what your friend is going through, what she is feeling. You might think you do, but you don’t. You can’t.

The fact that you don’t share the bond of cancer, though, doesn’t mean you can’t be helpful, supportive, and caring. You can be all of these by listening. Some of the most supportive people in my life have never had cancer. It doesn’t matter. They are good friends in part because they are good listeners.

Listening does not entail giving advice.

They are two totally different acts. One requires that you listen while your friends talks. One involves you giving your opinion about how your friend can change and what she can do differently/better.

In times of active crisis, the best thing you can do is keep your opinions to yourself. Unless you truly know what that crisis feels like (the death of a child or spouse, a serious medical diagnosis, or a divorce, for example), your advice will fall into the category “things people-who-don’t-understand say.” For me, others’ advice usually misses its mark. The result? I feel further misunderstood; therefore, I am more isolated.